LSAT 119 – Section 3 – Question 24

LSAT 119 - Section 3 - Question 24

June 2005You need a full course to see this video. Enroll now and get started in less than a minute.

Target time: 1:21

This is question data from the 7Sage LSAT Scorer. You can score your LSATs, track your results, and analyze your performance with pretty charts and vital statistics - all with a Free Account ← sign up in less than 10 seconds

| Question QuickView |

Type | Tags | Answer Choices |

Curve | Question Difficulty |

Psg/Game/S Difficulty |

Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT119 S3 Q24 |

+LR

| Sufficient assumption +SA Conditional Reasoning +CondR Link Assumption +LinkA | A

46%

168

B

5%

161

C

11%

159

D

19%

159

E

19%

163

|

157 166 174 |

+Hardest | 145.195 +SubsectionEasier |

J.Y.’s explanation

You need a full course to see this video. Enroll now and get started in less than a minute.

Summary

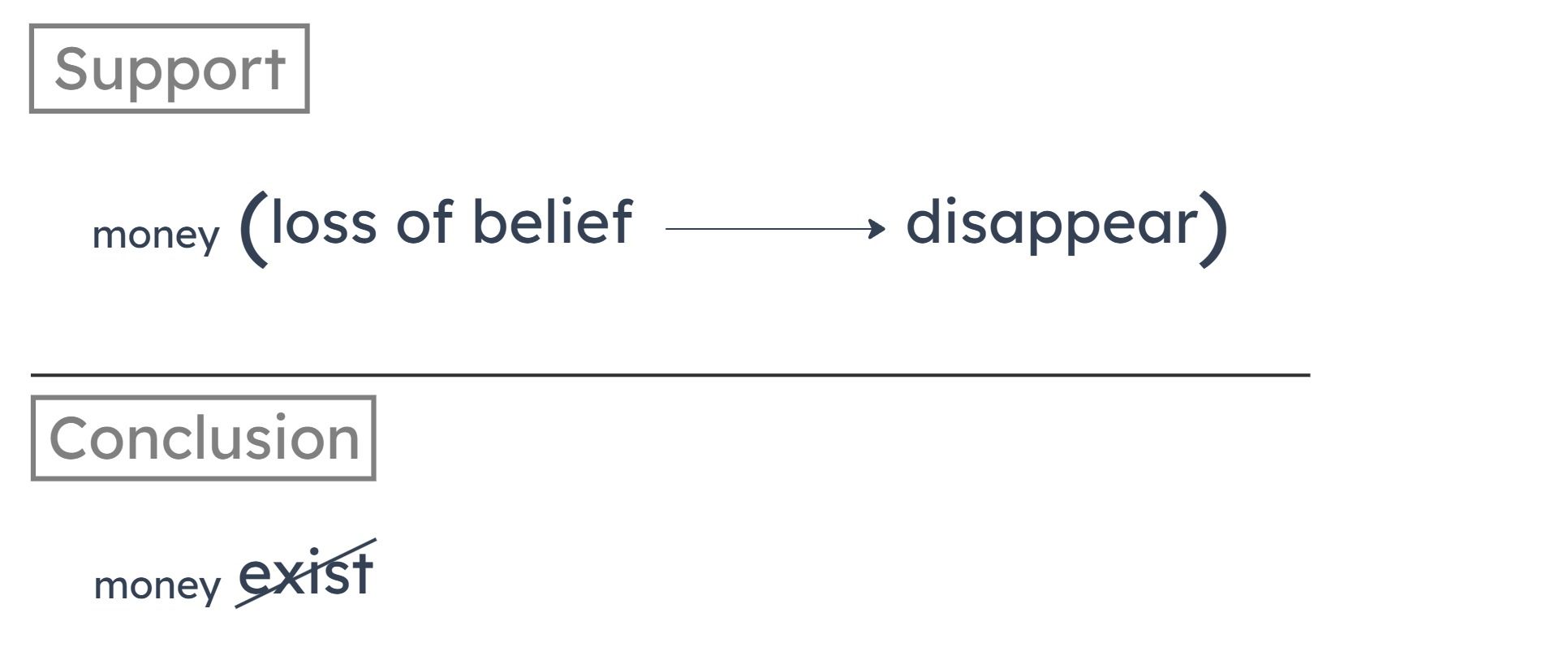

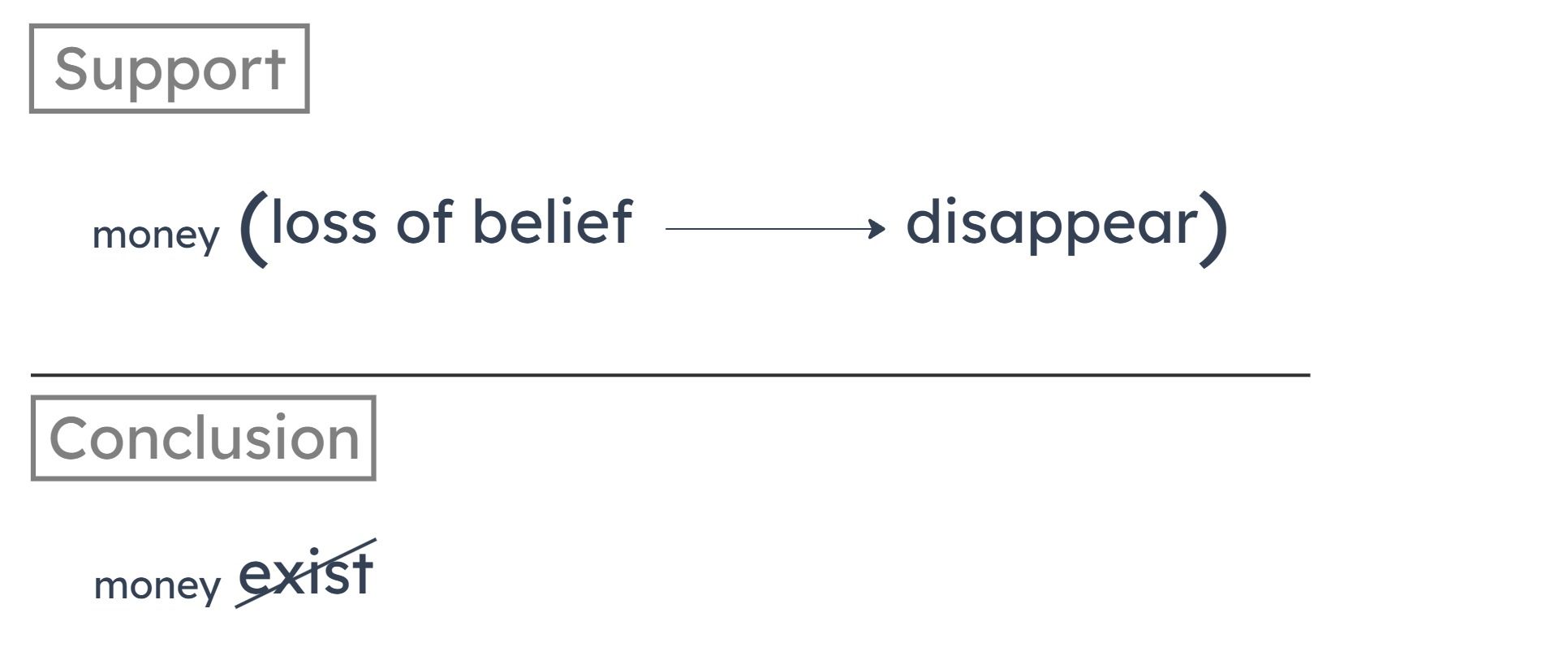

The author concludes that money doesn’t really exist. This is based on the following:

Money disappears if there’s a universal loss of belief in it. (The author follows up with an illustration of this occurring in financial markets.)

Money disappears if there’s a universal loss of belief in it. (The author follows up with an illustration of this occurring in financial markets.)

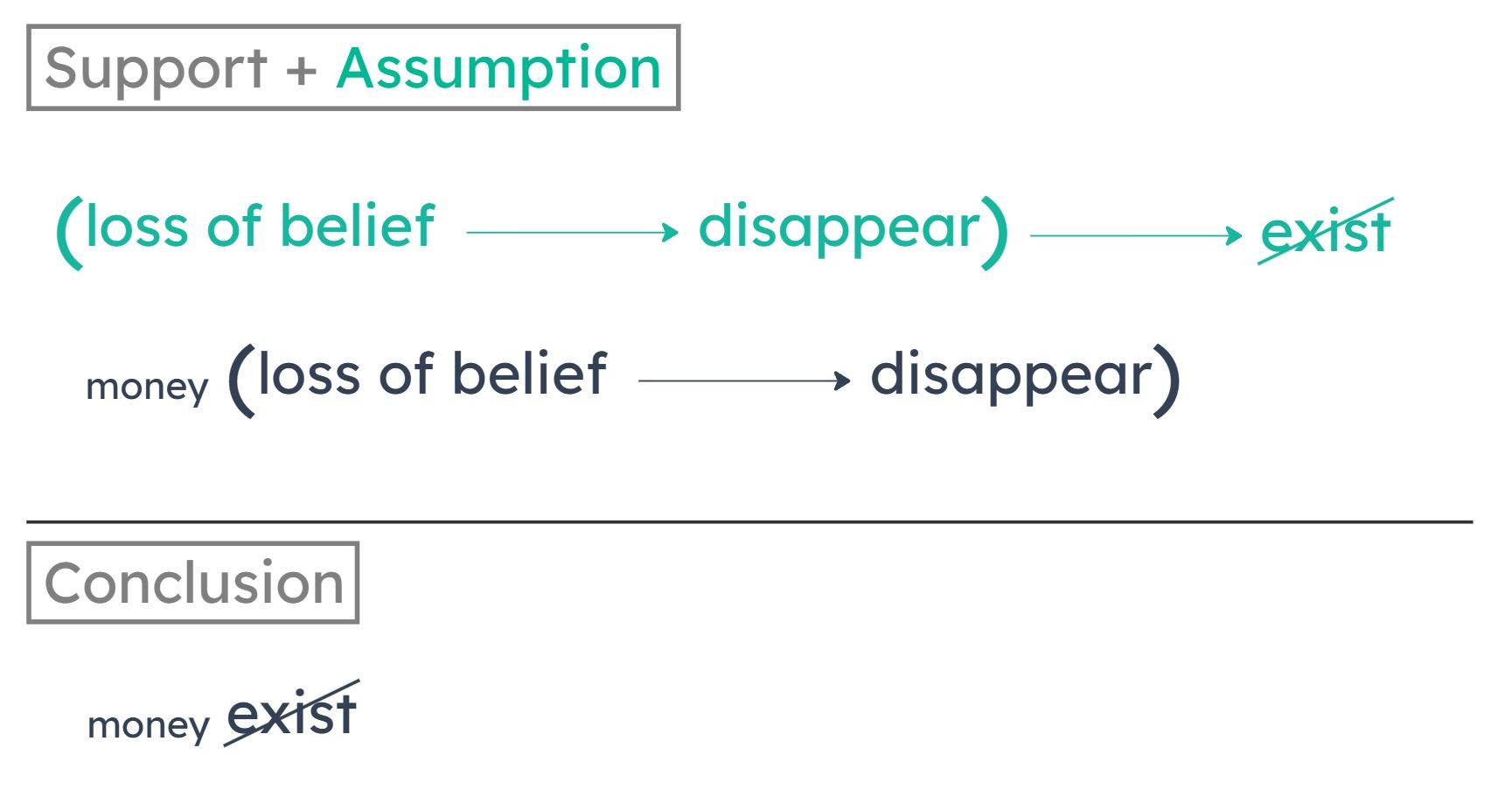

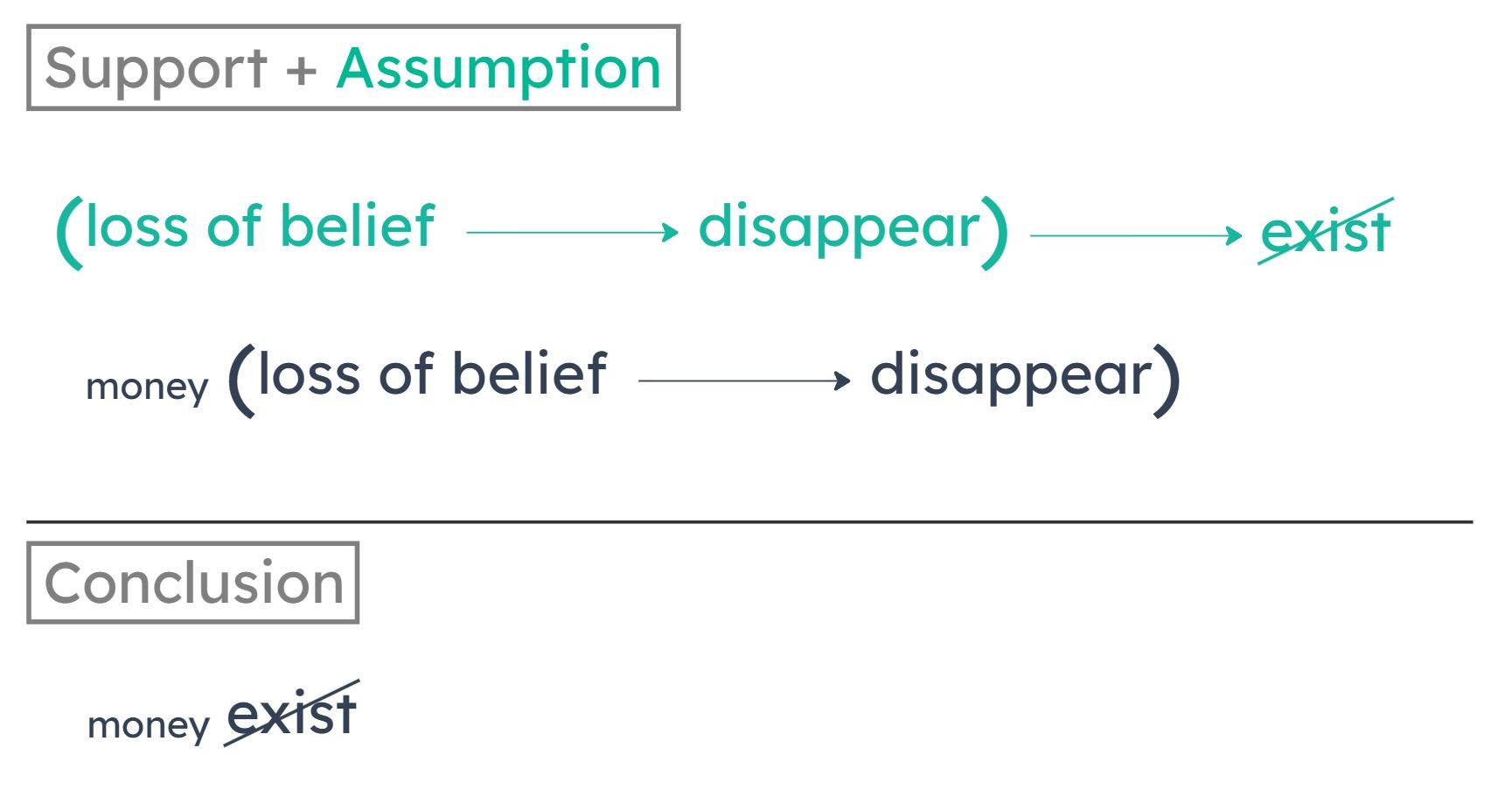

Missing Connection

The conclusion brings up the new concept of “does not really exist.” The premises don’t tell us how we can know that something does not really exist. To make the argument valid, we want to know that if universal loss of belief in something would make that thing disappear, then that thing does not really exist. Or, in other words, in order for something to exist, universal loss of belief in something would NOT make that thing disappear.

A

Anything that exists would continue to exist even if everyone were to stop believing in it.

(A) establishes that in order for something to exist, it must be the case that the thing would not disappear from a universal loss of belief. But since we know money does disappear from a universal loss of belief, we can conclude that money does not exist.

B

Only if one can have mistaken beliefs about a thing does that thing exist, strictly speaking.

The premises don’t establish that it’s impossible to have mistaken beliefs about money. So (B) doesn’t interact with the premises and does not establish the conclusion.

C

In order to exist, an entity must have practical consequences for those who believe in it.

The premises don’t establish that there are no practical consequences for those who believe in money. There could be many practical consequences for people who believe in money. So (C) doesn’t interact with the premises and does not establish the conclusion.

D

If everyone believes in something, then that thing exists.

(D) allows us to prove that something DOES exist. But we’re trying to prove that money does NOT exist.

E

Whatever is true of money is true of financial markets generally.

(E) establishes that what’s true of money is true of financial markets. But we’re not trying to conclude that something is true of financial markets. The contrapositive of (E) also would not help; we’re not trying to prove that, because something isn’t true of financial markets, it’s also not true of money.

Take PrepTest

Review Results

LSAT PrepTest 119 Explanations

Section 1 - Reading Comprehension

- Passage 1 – Passage

- Passage 1 – Questions

- Passage 2 – Passage

- Passage 2 – Questions

- Passage 3 – Passage

- Passage 3 – Questions

- Passage 4 – Passage

- Passage 4 – Questions

Section 2 - Logical Reasoning

- Question 01

- Question 02

- Question 03

- Question 04

- Question 05

- Question 06

- Question 07

- Question 08

- Question 09

- Question 10

- Question 11

- Question 12

- Question 13

- Question 14

- Question 15

- Question 16

- Question 17

- Question 18

- Question 19

- Question 20

- Question 21

- Question 22

- Question 23

- Question 24

- Question 25

Section 3 - Logical Reasoning

- Question 01

- Question 02

- Question 03

- Question 04

- Question 05

- Question 06

- Question 07

- Question 08

- Question 09

- Question 10

- Question 11

- Question 12

- Question 13

- Question 14

- Question 15

- Question 16

- Question 17

- Question 18

- Question 19

- Question 20

- Question 21

- Question 22

- Question 23

- Question 24

- Question 25

- Question 26

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment. You can get a free account here.