Summary

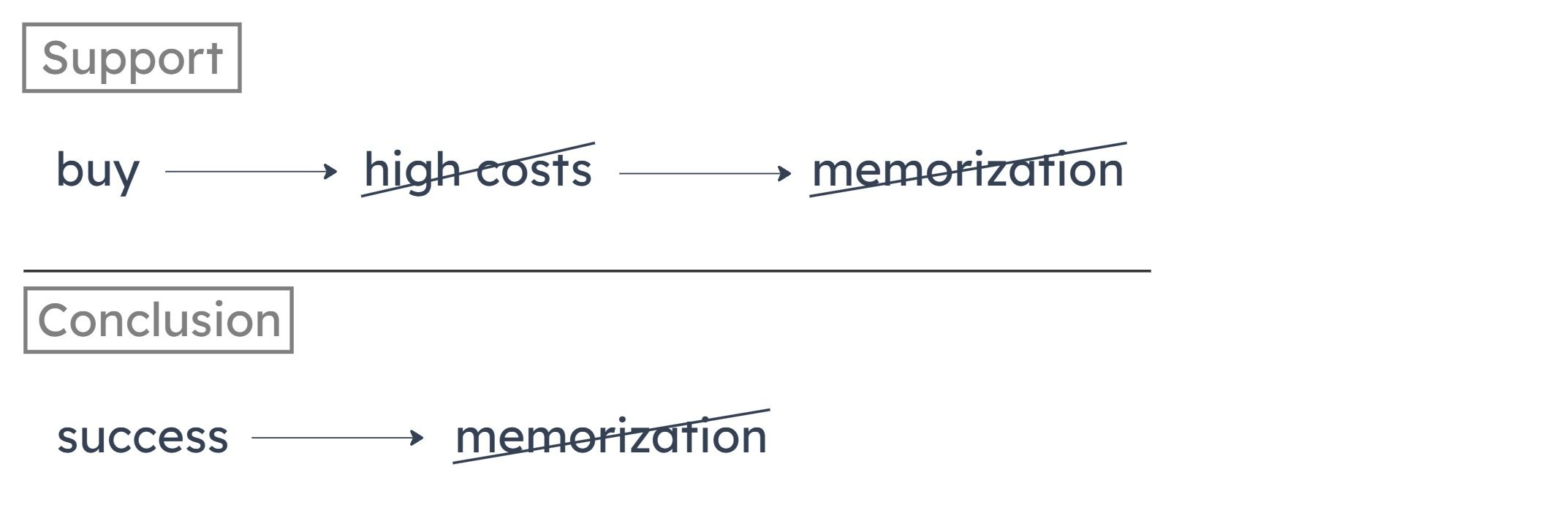

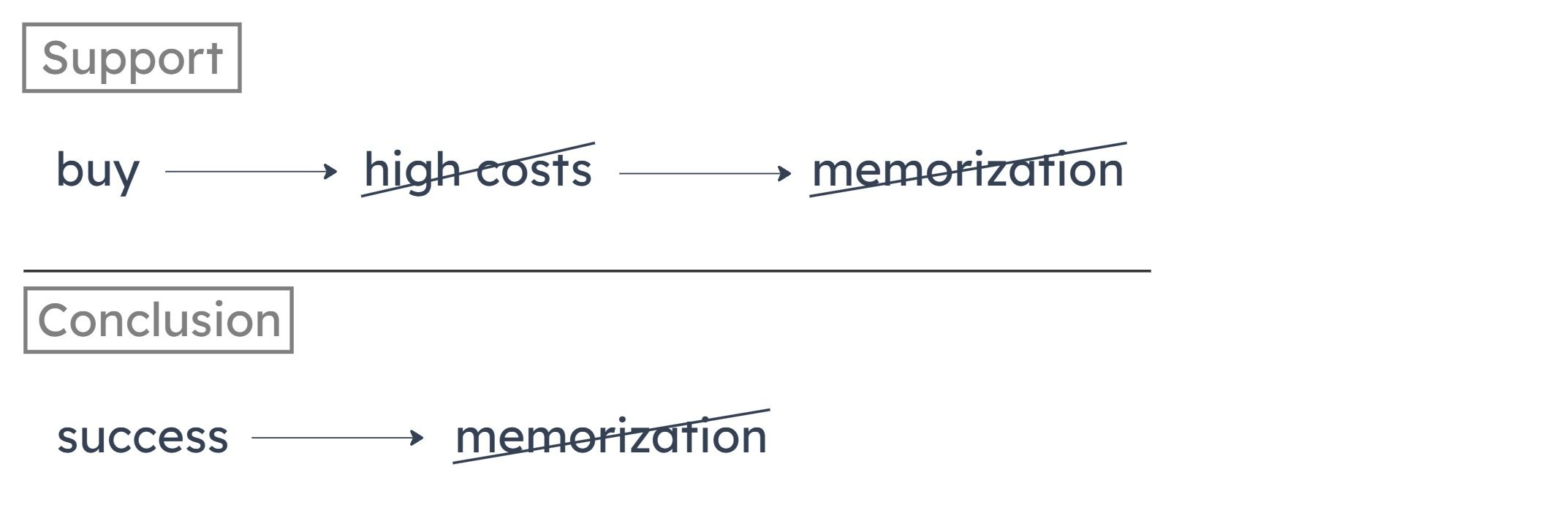

The argument concludes that in order to be successful, the software cannot demand memorization of unfamiliar commands. This is based on the following two premises:

If training costs are high, prime purchasers of the software won’t buy it.

If a software demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, then the training costs are high.

If training costs are high, prime purchasers of the software won’t buy it.

If a software demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, then the training costs are high.

Missing Connection

We want to reach the conclusion that if a software demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, it won’t be successful. “Won’t be successful” is a new concept in the conclusion; the premises don’t tell us what leads to lack of success.

But we do know from the two premises together that if a software demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, the prime purchasers won’t buy it.

If we learn that “prime purchasers won’t buy” establishes “unsuccessful,” that will establish that if a software demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, it won’t be successful. In other words, we want to learn that in order to be successful, a software needs prime purchasers to buy it.

But we do know from the two premises together that if a software demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, the prime purchasers won’t buy it.

If we learn that “prime purchasers won’t buy” establishes “unsuccessful,” that will establish that if a software demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, it won’t be successful. In other words, we want to learn that in order to be successful, a software needs prime purchasers to buy it.

A

If most prime purchasers of computer software buy a software product, that product will be successful.

(A) establishes what is sufficient for a software product to be successful. But we’re trying to establish what’s sufficient for a software product to be UNsuccessful. Or, you could also say that we’re looking for what’s necessary for the product to be successful. Learning what’s sufficient for success doesn’t prove what’s necessary for success.

B

Commercial computer software that does not require users to memorize unfamiliar commands is no more expensive than software that does.

(B) compares the expense of different kinds of software. But it doesn’t tell us anything about what’s required for success, or what’s sufficient to lead to lack of success.

C

Commercial computer software will not be successful unless prime purchasers buy it.

(C) establishes that in order for a software product to be successful, its prime purchasers must buy it. Since we know from the premises that if a product demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, prime purchasers won’t buy it, adding (C) now establishes that if a product demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, it won’t be successful.

D

If the initial cost of computer software is high, but the cost of training users is low, prime purchasers will still buy that software.

(D) doesn’t tell us anything about what’s required for success, or what’s sufficient to lead to lack of success.

E

The more difficult it is to learn how to use a piece of software, the more expensive it is to teach a person to use that software.

(E) doesn’t tell us anything about what’s required for success, or what’s sufficient to lead to lack of success.

Summarize Argument: Phenomenon-Hypothesis

The author concludes that eating less fat will help reduce cancer risk. He supports this by pointing to a correlation between cancer rates and fat intake: countries with higher cancer rates also have higher average fat intake.

Notable Assumptions

Based on a mere correlation, the author hypothesizes that higher fat intake is what’s causing the higher cancer rates. This means he assumes that the relationship isn’t the reverse (i.e., the higher cancer rates aren’t somehow causing higher fat intake), and also that there isn’t some hidden, alternative cause that’s actually responsible for the difference in cancer rates between different countries.

A

The differences in average fat intake between countries are often due to the varying makeup of traditional diets.

In order for this to weaken the argument, traditional diets would need to provide an alternative explanation for the difference in cancer rates between different countries. However, the possible effect of any given traditional diet on cancer rates is entirely unclear.

B

The countries with a high average fat intake tend to be among the wealthiest in the world.

In order for this to weaken the argument, the wealth of a country would need to provide an alternative explanation for the increased cancer rates in high-fat counties. However, the connection between increased national wealth and increased cancer likelihood is entirely unclear.

C

Cancer is a prominent cause of death in countries with a low average fat intake.

The stimulus tells us that cancer nevertheless occurs more commonly in countries with higher average fat intake. (C) fails to address any reason for that difference in cancer rates, and so fails to weaken the conclusion that the difference is due to fat intake.

D

The countries with high average fat intake are also the countries with the highest levels of environmental pollution.

This provides an alternative cause for the difference in cancer rates between different countries: it’s not fat intake that’s responsible, but rather exposure to pollution.

E

An individual resident of a country whose population has a high average fat intake may have a diet with a low fat intake.

The fact remains that, in general, high average fat intake correlates with high cancer rates. The possibility that someone’s fat intake might deviate from the average has no effect on the argument.

Summarize Argument

The author concludes that individuals who buy new cars today spend, on average, a larger amount relative to their incomes on a car than individuals spent 25 years ago. This is based on the fact that over the last 25 years, the average price paid for a new car has steadily increased in relation to the average individual income.

Notable Assumptions

The author assumes that the proportion of individuals who are buying cars today hasn’t significantly gone down. After all, if the proportion of individuals who buy cars has gone down, then it’s possible individuals still spend the same proportion of their income on cars; but other buyers (such as families or businesses) are paying a higher price and raising the average price of a car.

A

There has been a significant increase over the last 25 years in the proportion of individuals in households with more than one wage earner.

So, a higher proportion of households have more than one wage earner. But we’re talking about “individuals who buy new cars.” (A) doesn’t suggest that more households are buying a new car together.

B

The number of used cars sold annually is the same as it was 25 years ago.

The stimulus concerns changes in average price of a new car in relation to average income. The number of cars sold doesn’t affect average price of a car.

C

Allowing for inflation, average individual income has significantly declined over the last 25 years.

If income has gone down, that tends to support the position that individuals who buy new cars are spending a higher portion of their income than such individuals did 25 years ago.

D

During the last 25 years, annual new-car sales and the population have both increased, but new-car sales have increased by a greater percentage.

The stimulus concerns changes in average price of a new car in relation to average income. How many new cars are bought in relation to the population doesn’t affect the average price of a new car or how it relates to the average income.

E

Sales to individuals make up a smaller proportion of all new-car sales than they did 25 years ago.

This shows how the increase in average new car price can be explained by a greater portion of sales to non-individuals (such as a business). So, the increase in average price in relation to individual income doesn’t have to mean individuals are paying more for their cars.

Summary

Poets preserve languages, because only poetry cannot be translated well. If we could get everything written in a translation, then we would not bother to learn a language. Therefore, since we cannot observe the beauty of poetry except in the language in which it is written, we have motivation to learn the language.

Strongly Supported Conclusions

We should note that, since this is an “except” question, any strongly supported conclusion would be an incorrect answer choice. We’re looking for an answer choice that is unsupported or least supported. Some strongly supported conclusions could include:

If we bother to learn a language, then there must be poetry in that language.

Preserving a language involves motivating at least some people to learn that language.

The desire to witness the beauty of poetry motivates at least some people to learn a language.

If we bother to learn a language, then there must be poetry in that language.

Preserving a language involves motivating at least some people to learn that language.

The desire to witness the beauty of poetry motivates at least some people to learn a language.

A

All nonpoetic literature can be translated well.

The stimulus concedes that any nonpoetic form of literature can be translated well. We are told only poetry cannot be translated well.

B

One purpose of writing poetry is to preserve the language in which it is written.

The stimulus does not provide any information regarding the purpose of writing poetry. We only know, rather, the consequences or results of writing poetry.

C

Some translations do not capture all that was expressed in the original language.

The stimulus concedes that some translations do not capture everything expressed in the original language. Our main example is poetry, and we know from the stimulus that only poetry cannot be translated well.

D

The beauty of poetry is not immediately accessible to people who do not understand the language in which the poetry was written.

The stimulus concedes that one cannot understand the beauty of poetry except in the language it is written in. If someone does not understand that language, the poetry’s beauty would not be immediately accessible.

E

Perfect translation from one language to another is sometimes impossible.

The stimulus concedes that sometimes perfect translation between languages is impossible. Our main example is poetry, and we know from the stimulus that only poetry cannot be translated well.