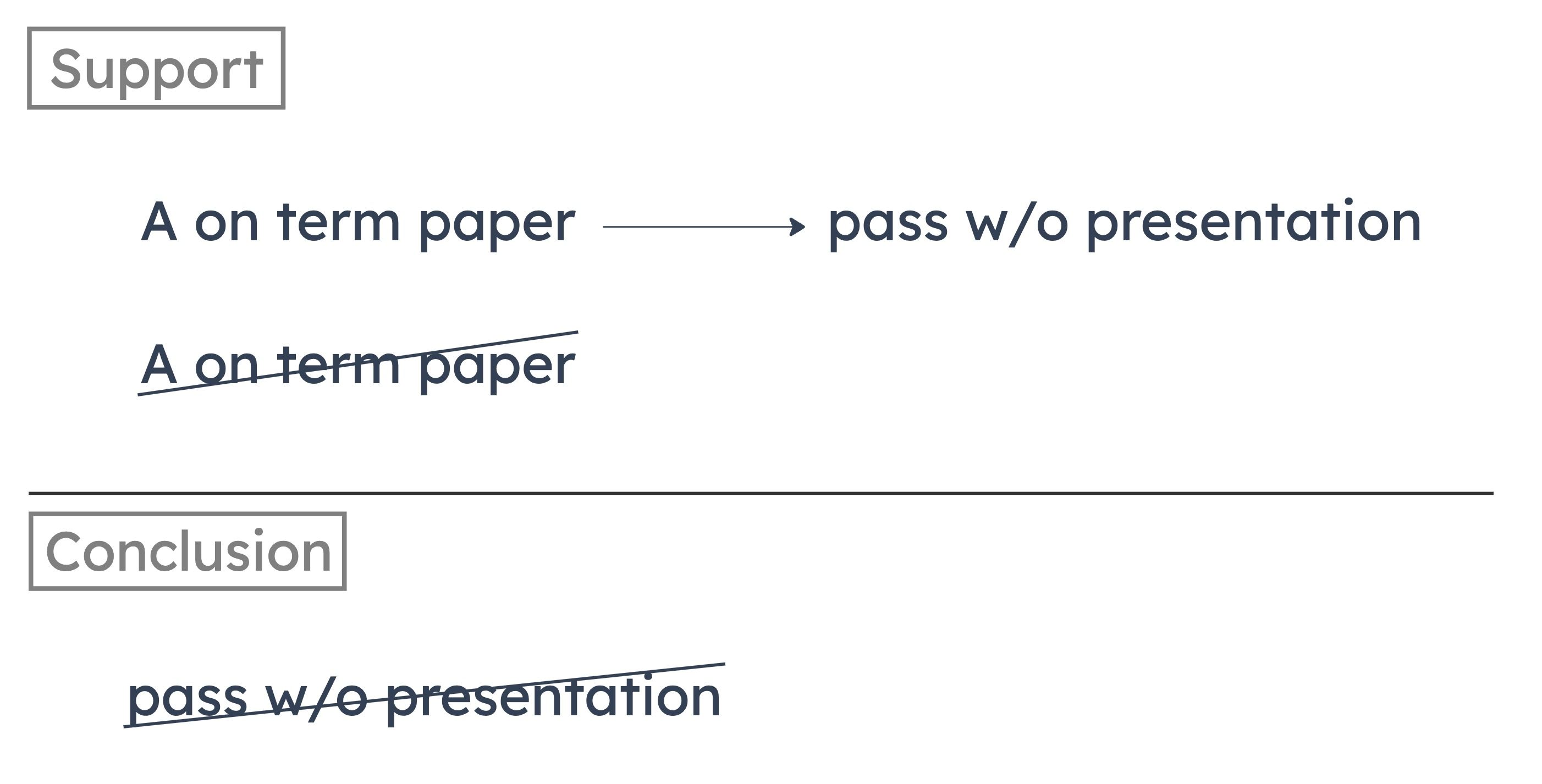

Summarize Argument

The author concludes that Joan will have to do the class presentation to pass the course. He supports this by saying that if she’d gotten an A on her term paper, she could pass the course without doing the presentation, but she didn’t get an A on her term paper.

Identify and Describe Flaw

This is the flaw of mistaking sufficiency for necessity. The author treats “A on term paper” as necessary for “pass without presentation.” But in his premises, “A on term paper” is merely sufficient. So not getting an A on the term paper tells us nothing about whether she can pass the course without doing the presentation.

Maybe there are other ways Joan can pass the course without doing the presentation. For example, maybe if she got a B on the term paper, she’ll still pass without doing the presentation.

A

ignores the possibility that Joan must either have an A on her term paper or do the class presentation to pass the course

Like (D), the author doesn't ignore this possibility. In fact, he mistakenly assumes that it’s the only possibility. He assumes that Joan has to either have an A on the paper or do the presentation in order to pass.

B

presupposes without justification that Joan’s not getting an A on her term paper prevents her from passing the course without doing the class presentation

The author assumes without justification that just because Joan didn’t get an A on her term paper, she can’t pass the course without doing the presentation. But maybe there are other ways, like getting a B on the paper, that Joan can still pass without doing the presentation.

C

overlooks the importance of class presentations to a student’s overall course grade

The author isn’t concerned about Joan’s overall course grade. He only discusses whether or not she’ll pass the course.

D

ignores the possibility that if Joan has to do the class presentation to pass the course, then she did not get an A on her term paper

Like (A), the author doesn't ignore this possibility. He claims that if she needs the presentation to pass, then she didn’t get an A on the paper.

E

fails to take into account the possibility that some students get A’s on their term papers but do not pass the course

Other students’ outcomes are irrelevant. The argument is only addressing Joan.

Summary

The solidity of bridge piers is based mainly on the depth of the pilings. Before 1700, pilings were driven to “refusal,” which is the point at which the piling don’t go any deeper.

The Rialto Bridge’s pilings met the “contemporary standard for refusal” as of 1588. According to this standard, the pilings were driven into the ground until additional penetration into the ground was not greater than two inches after 24 hammer blows.

The Rialto Bridge’s pilings met the “contemporary standard for refusal” as of 1588. According to this standard, the pilings were driven into the ground until additional penetration into the ground was not greater than two inches after 24 hammer blows.

Very Strongly Supported Conclusions

There’s no clear conclusion to anticipate. But notice that there’s a difference between “refusal” and the “contemporary standard for refusal” in 1588. The definition of “refusal” involves pilings that can’t go any deeper. But the “contemporary standard for refusal” in 1588 allowed for the pilings to go deeper — just not deeper than two inches per 24 hammer blows.

A

The Rialto Bridge was built on unsafe pilings.

We don’t know what pilings are safe or unsafe. We know that solidity depends on pilings, but we have no basis to say that the depth at which the Rialto pilings were driven was safe or unsafe.

B

The standard of refusal was not sufficient to ensure the safety of a bridge.

We don’t know what depth of pilings is safe or unsafe. We know that solidity depends on pilings, but we have no basis to say that the contemporary standard of refusal was safe or unsafe.

C

Da Ponte’s standard of refusal was less strict than that of other bridge builders of his day.

We don’t know the standard that Da Ponte used. We know that his pilings met the standard for refusal as of 1588, but we don’t know whether Da Ponte used this standard or whether his standard was more or less strict than anyone else’s.

D

After 1588, no bridges were built on pilings that were driven to the point of refusal.

We don’t know whether there were any bridges built to the point of refusal after 1588. Maybe there were some driven to the point of refusal in 1589; we have no idea.

E

It is possible that the pilings of the Rialto Bridge could have been driven deeper even after the standard of refusal had been met.

This is supported by the last sentence. The contemporary standard of refusal still allowed the pilings to be driven deeper — just not more than 2 inches deeper per 24 hammer blows. But, for example, the pilings might have been driven 1 inch deeper after 24 hammer blows, or even just 1 millimeter deeper.