In reality, personality disorders might cause the increase in theta waves, or another factor could be causing both. In either of these cases, the researcher’s link between watching TV and developing personality disorders falls apart.

A

uses the phrase “personality disorders” ambiguously

B

fails to define the phrase “theta brain waves”

C

takes correlation to imply a causal connection

D

draws a conclusion from an unrepresentative sample of data

E

infers that watching TV is a consequence of a personality disorder

A

Levels of pesticides in the environment often continue to be high for decades after their use ends.

B

Lake Laberge’s water contains high levels of other pesticides besides toxaphene.

C

Toxic chemicals usually do not travel large distances in the atmosphere.

D

North American manufacturers opposed banning toxaphene.

E

Toxic chemicals become more readily detectable once they enter organisms the size of fish.

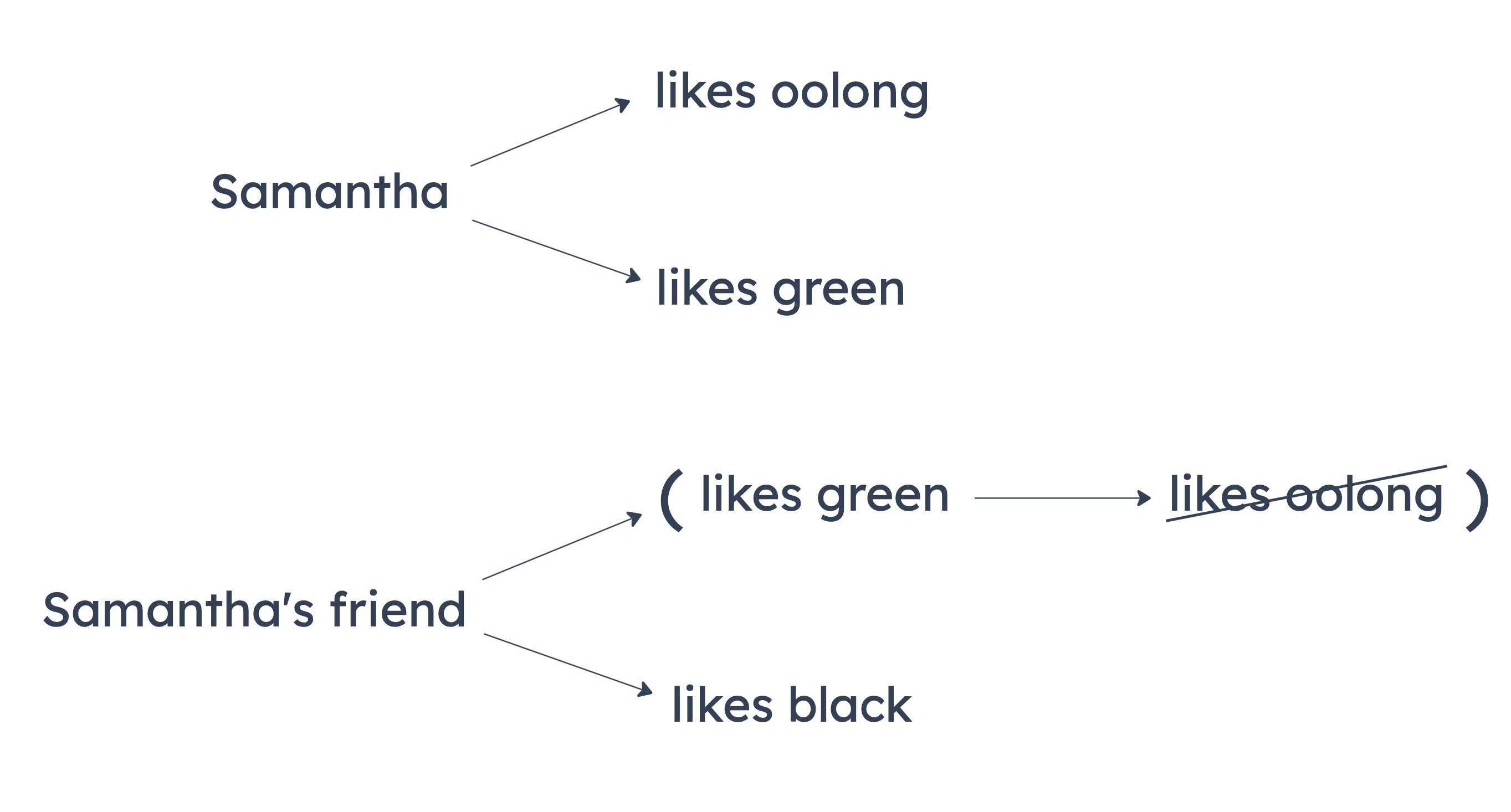

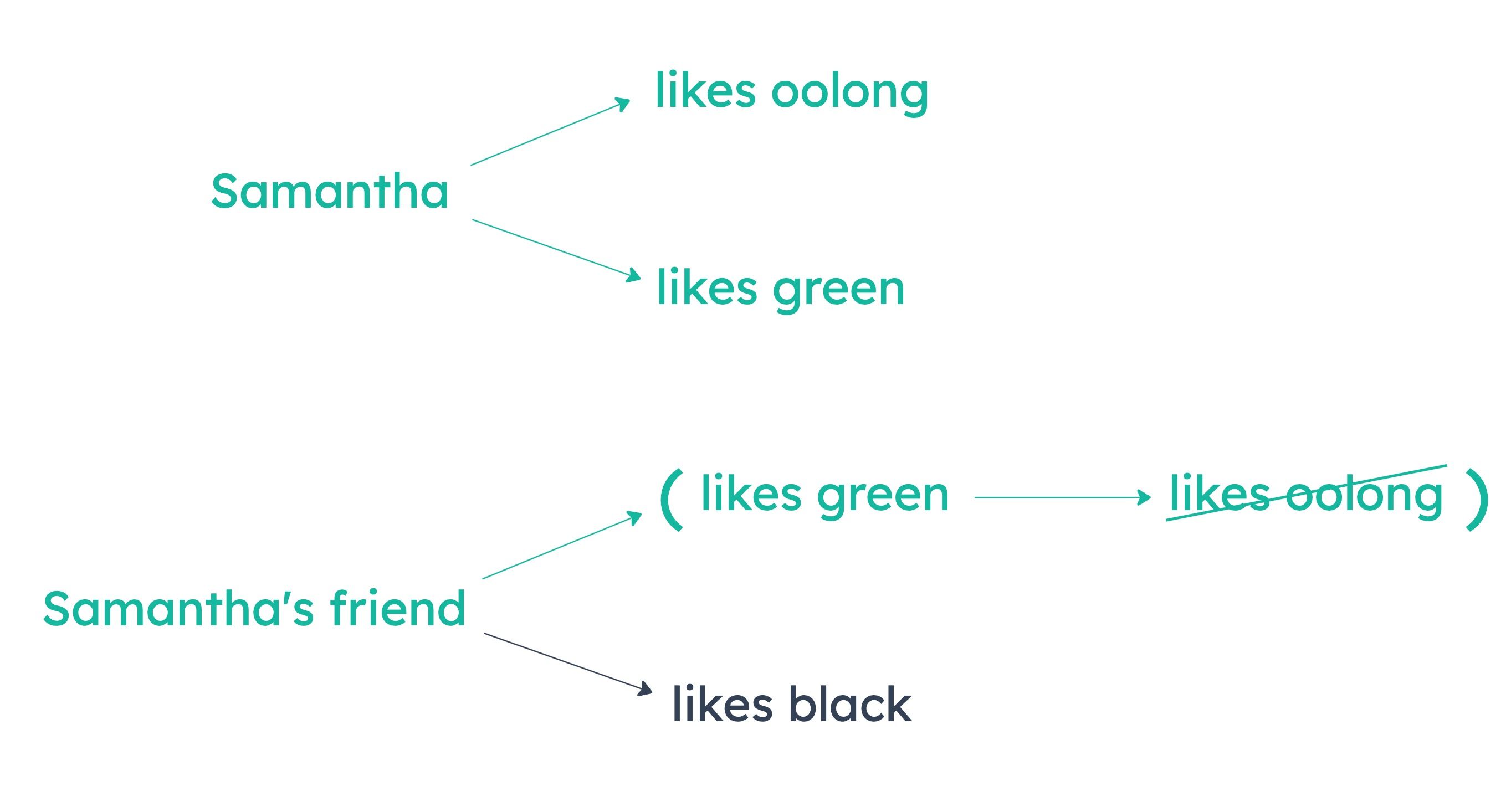

A

Samantha likes black tea.

B

None of Samantha’s friends likes green tea.

C

Samantha’s friends like exactly the same kinds of tea as each other.

D

One of Samantha’s friends likes neither oolong nor green tea.

E

One of Samantha’s friends likes all the kinds of teas that Samantha likes.

A slower and more natural rhythm of life does not necessarily decrease rates of illness and stress.

The common wisdom that country life is healthier and more relaxed than city life is not supported by data.

A

Living in the country is neither healthier nor more relaxing than living in the city.

B

Living in the country does not in fact permit a slower and more natural rhythm of life than living in the city.

C

People whose rhythm of life is slow and natural recover quickly from illness.

D

Despite what people believe, a natural rhythm of life is unhealthy.

E

The amount of stress a person experiences depends on that person’s rhythm of life.

In other words, he assumes that the environmentalists’ conclusion is false simply because their support is weak.

A

impugns the motives of the residents rather than assessing the reasons for their contention

B

does not consider the safety of emissions from other sources in the area

C

presents no testimony from scientists that the emissions are safe

D

fails to discuss the benefits of the factory to the surrounding community

E

equivocates between two different notions of the term “health risk”

A

The technological revolution that started in the early eighteenth century in England resulted in increased trade between England and Scotland.

B

Reductions in tariffs on foreign goods in 1752 led to an increase in imports to Glasgow.

C

The establishment of banking in Glasgow encouraged the use of paper money, which made financial transactions more efficient.

D

Improvements in Scottish roads between 1750 and 1758 facilitated trade between Glasgow and the rest of Scotland.

E

The initial government regulation of Scottish banks stimulated Glasgow’s economy.

A

Preschoolers have a tendency to imitate adults, and most adults follow strict routines.

B

Children intensely curious about new things have very short attention spans.

C

Some older children also develop strict systems that help them learn.

D

Preschoolers ask as many creative questions as do older children.

E

Preschool teachers generally report lower levels of stress than do other teachers.

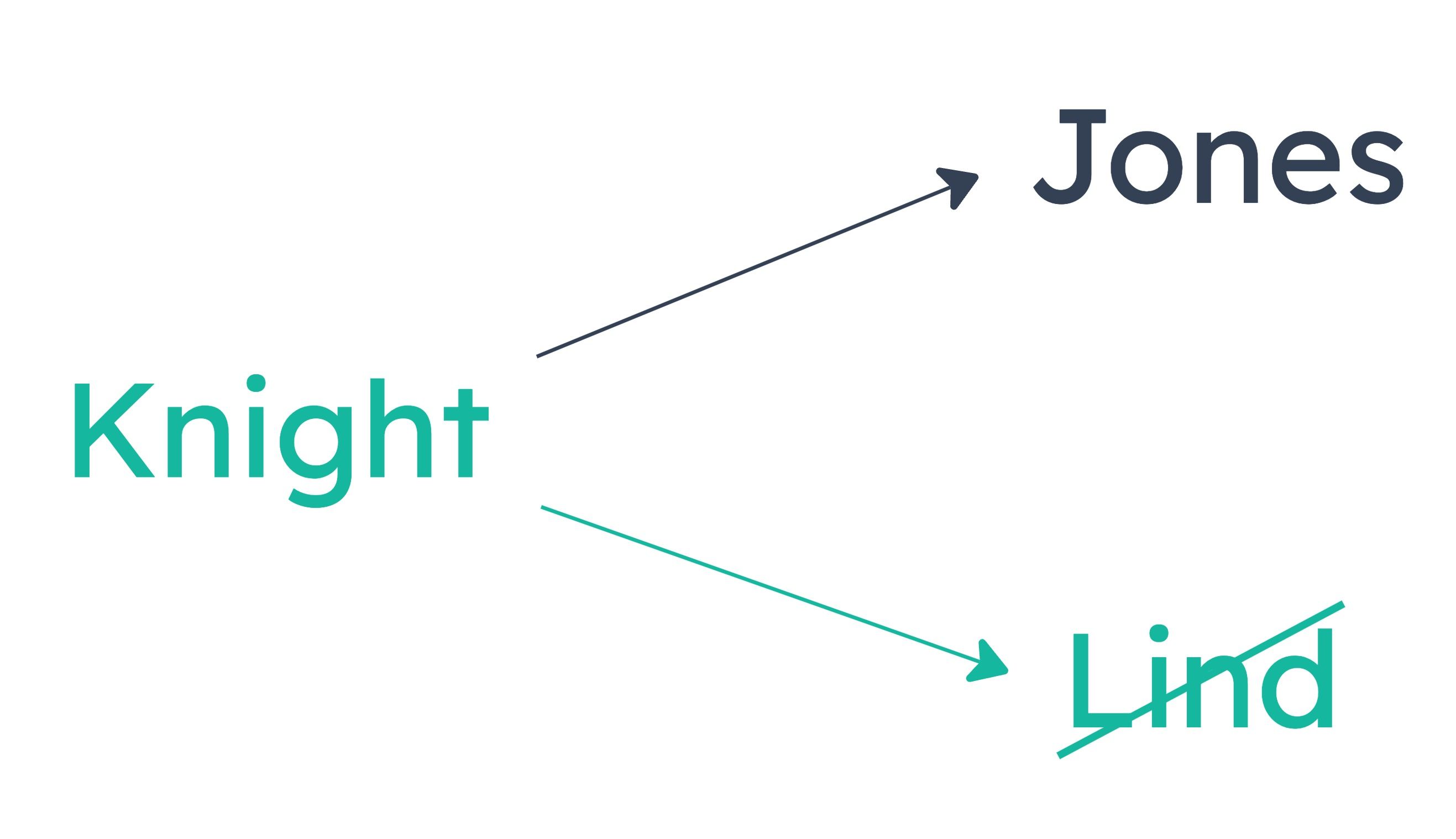

There can be a maximum of two authors in the textbook.

A

If the textbook contains an essay by Lind, then it will not contain an essay by Knight.

B

The textbook will contain an essay by only one of Lind, Knight, and Jones.

C

The textbook will not contain an essay by Knight.

D

If the textbook contains an essay by Lind, then it will also contain an essay by Jones.

E

The textbook will contain an essay by Lind.

A

takes for granted that no items in a body of circumstantial evidence are significantly more critical to the strength of the evidence than other items in that body

B

presumes, without providing justification, that the strength of a body of evidence is less than the sum of the strengths of the parts of that body

C

fails to consider the possibility that if many items in a body of circumstantial evidence were discredited, the overall body of evidence would be discredited

D

offers an analogy in support of a conclusion without indicating whether the two types of things compared share any similarities

E

draws a conclusion that simply restates a claim presented in support of that conclusion

The question stem reads: The reasoning in the lawyer's argument is most vulnerable to criticism on the grounds that the argument… This is a Flaw question.

The lawyer begins by making an analogy. He claims that a body of circumstantial evidence is similar to a rope. He claims that each piece of evidence is like a strand in that rope: just as adding more strings to the rope makes a rope stronger, adding more pieces of evidence strengthens the body of evidence. He then describes how if a strand of a rope is broken, the rope does not break, and it still retains much of its strength. He concludes that, similarly, if you discredit ("break") a few pieces of evidence, the overall body of evidence is still strong.

When analyzing an argument that uses an analogy, a good first step is to ask yourself, "Are the two things being compared actually similar?" As you increase the points of difference between the two things being compared, the analogy's strength diminishes. In this case, we want to determine where the lawyer's analogy between ropes and bodies of evidence frays apart. The idea that adding pieces of evidence to the body increases the strength of the body, like adding strands to a rope, makes sense and seems like a pretty good point of comparison. However, the analogy fails when we consider the fact that strands of rope are all the same. However, not all pieces of evidence are equal: some add much more strength than others. You have experience with this on the LSAT. Take away a premise that strengthens the argument, and the argument can survive. Take away a premise necessary to the argument, and the argument falls apart. So if we took away a few pieces of necessary evidence, the body would fall apart. However, that is contrary to the lawyer's conclusion. If you didn't see this, that is ok! When doing POE, prioritize answer choices that draw a distinction between ropes and bodies of evidence.

Correct Answer Choice (A) is what we discussed. The lawyer takes for granted that no evidence is more important to the body than others.

Answer Choice (B) is wrong. If you picked (B), you likely had trouble determining what (B) means. (B) says to take the strength of each piece of evidence independently and add them up. That will be greater than the strength of the evidence if you take the pieces altogether. If anything, the opposite is true: adding many pieces of circumstantial evidence together tends to count as better evidence than taking each individually.

Answer Choice (C) is not a problem for the argument. If you interpret "many = few": The point of the lawyer's argument is to show that if you take away some strands of evidence, then the body retains its strength, so the possibility is addressed. If you interpret "many"> few": then sure, the possibility is ignored. However, that is not a problem for the argument because the lawyers' conclusion is limited to taking away a few pieces of evidence. Either way, the argument is not flawed because of (C).

Answer Choice (D) is tempting, but we run into problems with the word "any." The lawyer has indicated that bodies of evidence share similarities to ropes. Adding more pieces of evidence or strands increases the strength of both.

Answer Choice (E) is incorrect. The lawyer does not use his own premise as a conclusion.