A

The ruined ships and boats around Shooter’s Island have been there for decades.

B

The number of juvenile waterbirds around Shooter’s Island, as well as the number around each neighboring island, does not fluctuate dramatically throughout the year.

C

Waterbirds use still waters as nurseries for juveniles whenever possible.

D

The waters around the islands neighboring Shooter’s Island are much rougher than the waters around Shooter’s Island.

E

Waterbirds are typically much more abundant in areas that serve as nurseries for juvenile waterbirds than in areas that do not.

Further Explanation

Pretty hard question.

Premises tell us that Shooter Island's waters are exceptionally still and that there are lots of juvenile birds gathered around its waters. There aren't very many juvenile birds in waters in neighboring islands. We have to catch on that we are not told WHY the juveniles are gathering in still waters/Shooter Island. It could be for any number of reasons. The conclusion says that it's because it's their nursery. Okay, that makes sense I guess baby birds like still waters. They're probably using it as a nursery and that's why there are so many juvenile birds there.

If you thought that, then you likely overlooked (C). (C) tells us that whenever possible, waterbirds use still water as nurseries. We think... don't we already know that? Nope, we don't. This is a really powerful assumption that if established, would do wonders for the argument.

(C) tells us waterbird's preference is to use still waters for nurseries whenever it's possible. The stimulus tells us that there are in fact an overabundance of juveniles in still waters. You put the two statements together and now we're pretty sure that they're actually there because they're using it as a nursery and not for some other reason. Our argument is made much better.

(D) is an attractive trap. It says that the waters around the other islands are MUCH rougher. This seems like new information but it hardly is. We already knew from the premises that Shooter Island water is EXCEPTIONALLY still. Not just kind of still. It's exceptionally still. So even if the neighboring waters are a little bit rough, they're MUCH rougher than exceptionally still.

But let's just say that the waters in the neighboring islands are truly objectively rough. Okay, we still don't know why juvenile birds are gathering in still waters/Shooter Island. Is it as the conclusion says that it's because this is their nursery? Maybe. Or maybe it's for some other reason. That means the argument was as strong/weak as it ever was. We didn't do our job of strengthening the argument.

A

Because no single person is the author of a folktale, folktales must reflect the values of a culture rather than those of an individual.

B

Folktales are often oral traditions that persist from times when few people left written materials.

C

The manner in which a culture adapts its narratives reveals information about the values of that culture.

D

The ancient narratives persist largely because they speak to basic themes and features of the human condition.

E

Folktales are often morality tales, used to teach children the values important to a culture.

It has been argued that the immense size of Tyrannosaurus rex would have made it so slow that it could only have been a scavenger, not a hunter, since it would not have been able to chase down its prey. This, however, is an overly hasty inference. T. rex’s prey, if it was even larger than T. rex, would probably have been slower than T. rex.

Summarize Argument: Counter-Position

The author concludes that the theory that Tyrannosaurus rex was exclusively a scavenger is an overly hasty inference. As support for this conclusion, the author addresses a possibility that those who believe that T. rex was a scavenger fail to consider: that the prey of T. rex could be even larger than T. rex. If this was the case, then the prey would probably have been slower than T. rex. This possibility weakens the theory that T. rex was primarily a scavenger.

Identify Argument Part

The claim in the question stem is the inference that the author concludes was made too hastily.

A

It is a hypothesis that is claimed in the argument to be logically inconsistent with the conclusion advanced by the argument.

The conclusion advanced by the argument is just that the theory that T. rex was exclusively a scavenger is a hasty inference. There is no logical inconsistency here; the author is just asserting that the given evidence is not enough.

B

It is a hypothesis that the argument contends is probably false.

The author does not claim that the hypothesis in the question stem is probably false––this language is too strong. The author only claims that this hypothesis was “overly hasty,” meaning that we cannot make this conclusion from the information given.

C

It is a hypothesis that the argument attempts to undermine by calling into question the sufficiency of the evidence.

In asserting that the claim in the question stem is “overly hasty,” the author is saying that this claim doesn’t have enough support, not that it’s false. This is why (C) is correct––the author claims that the evidence is not sufficient to claim that T. rex was a scavenger.

D

It is offered as evidence in support of a hypothesis that the argument concludes to be false.

The claim in the question stem is the hypothesis that the author is discussing; it is not offered as evidence of a hypothesis.

E

It is offered as evidence that is necessary for drawing the conclusion advanced by the argument.

The statement in the question stem is the hypothesis that the author claims was an overly hasty inference; it is not offered as evidence.

A

Solving a philosophical paradox requires accepting something that intuitively seems to be incorrect.

B

The conclusion of a philosophical paradox cannot be false if all the paradox’s premises are true.

C

Philosophical paradoxes with one or two premises are more baffling than those with several premises.

D

Any two people who attempt to solve a philosophical paradox will probably use two different approaches.

E

If it is not possible to accept that the conclusion of a particular philosophical paradox is true, then it is not possible to solve that paradox.

A

they will sometimes withhold comment in situations in which they would otherwise be willing to speak

B

they will sometimes treat those in the latter group in a manner the members of this latter group do not like

C

those in the latter group must be guided by an entirely different principle of behavior

D

those in the latter group will respond by concealing unpleasant truths

E

the result will meet with the approval of both groups

(1) The causal relationship could be reversed—maybe people with more severe symptoms are more likely to take cold medicine!

(2) Some other factor could be causing the correlation—for example, maybe in parts of the world where colds tend to be more severe, cold medicine also happens to be more widely available.

A

treats something as true simply because most people believe it to be true

B

treats some people as experts in an area in which there is no reason to take them to be reliable sources of information

C

takes something to be true in one case just because it is true in most cases

D

rests on a confusion between what is required for a particular outcome and what is sufficient to cause that outcome

E

confuses what is likely the cause of something for an effect of that thing

A

Children apparently have a reasonably sophisticated understanding of what is real and what is pretend.

B

Children who have acquired a command of language generally answer correctly when asked about whether a thing is real or pretend.

C

Even a very young child can tell the difference between a lion and someone pretending to be a lion.

D

Children would be terrified if they believed they were in the presence of a real lion.

E

The pleasure children get from make-believe would be impossible to explain if they could not distinguish between what is real and what is pretend.

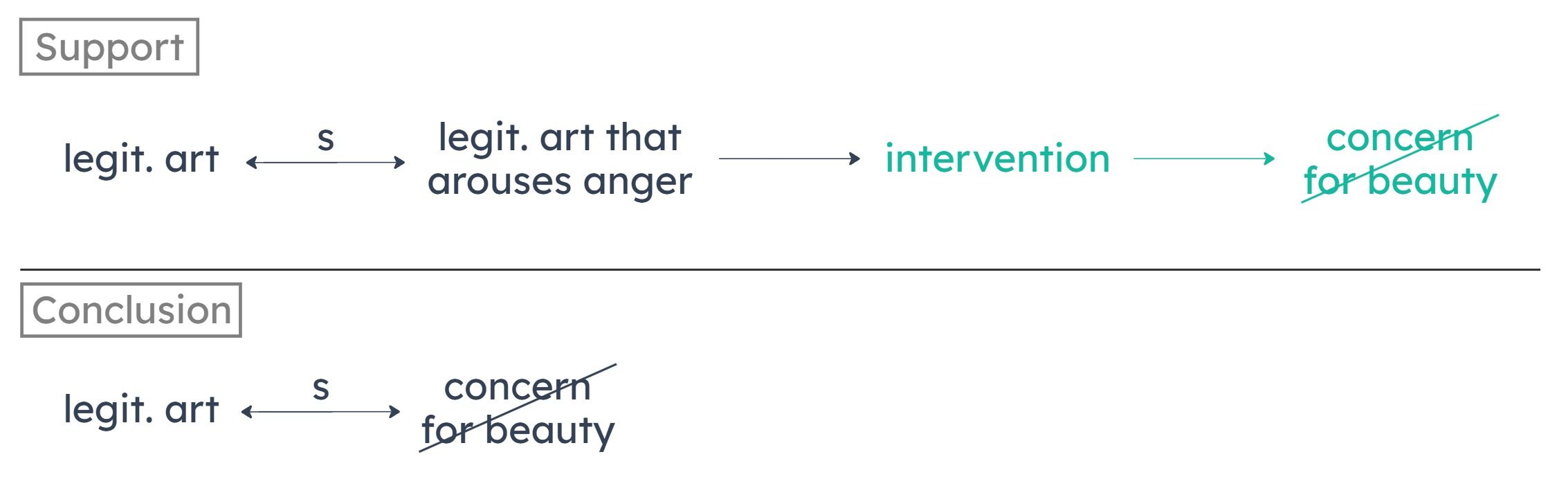

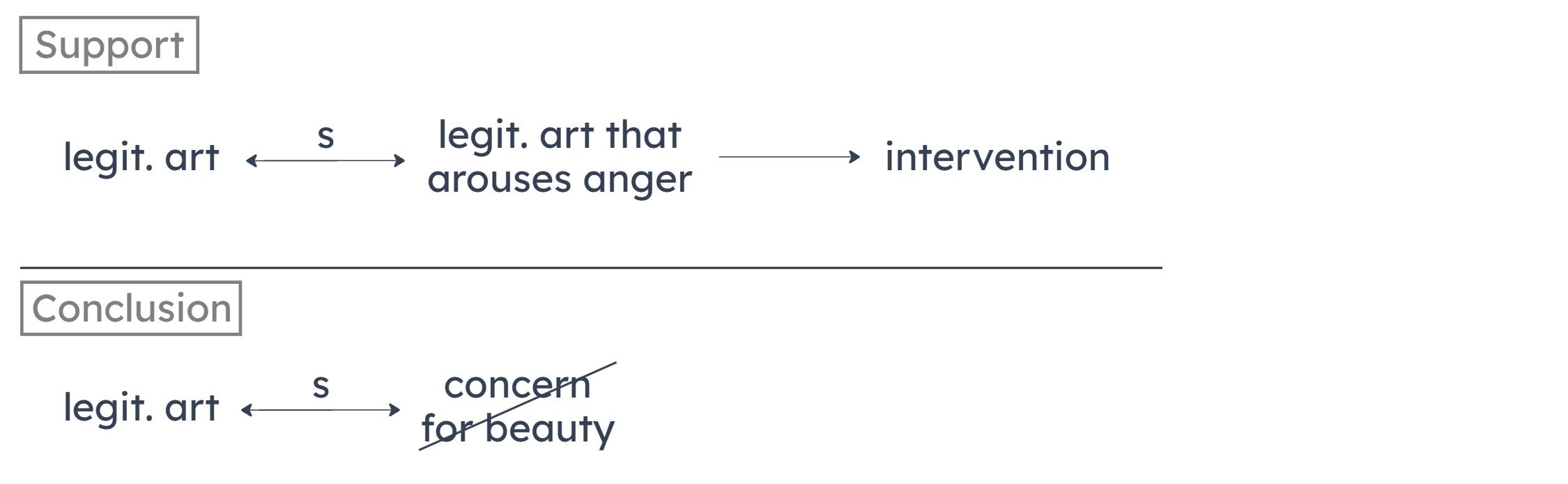

Some legitimate art aims to arouse anger.

All legitimate art with the aim of arousing anger intentionally calls for concrete intervention.

To go further, we can anticipate some specific relationships that could get us from the premise to the concept “not concerned with beauty.” We know from the premises that some legitimate art aims to arouse anger. We also know that some legitimate art calls for concrete intervention. Either of these could make the argument valid:

Any art that aims to arouse anger is not concerned with beauty.

Any art that calls for concrete intervention is not concerned with beauty.

A

There are works that are concerned with beauty but that are not legitimate works of art.

B

Only those works that are exclusively concerned with beauty are legitimate works of art.

C

Works of art that call for intervention have a merely secondary concern with beauty.

D

No works of art that call for intervention are concerned with beauty.