The question stem says the reasoning in which one of the following is most strongly supported by the guidelines. This is a rarer type of question though we have seen it plenty before. It’s like MSS in that the support flows down from the stimulus into the answers. They're asking us to take the guidelines in the stimulus and push them into the arguments in the answers to improve their reasoning. But that’s like a PSA question. Instead of the stimulus containing an argument searching for a conditional in the answer, it's the other way around. The stimulus contains a conditional searching for an argument. This is a cosmetic difference.

The stimulus gives us a ton of rules in conditional form. The first one is that if a radiant floor cooling system is to be installed or if it is to be a luxury hotel, then a radiant floor heating system must be installed. The sufficient condition here is a disjunctive, it's "or." That means we can split the arrow, so to speak. A radiant floor cooling system and a luxury hotel are each independently sufficient to demand the installation of radiant floor heating.

rf-cool → rf-heat

luxury → rf-heat

The next sentence is the only other conditional. It hooks up to radiant floor cooling. It says a radiant floor cooling system should not be installed in any hotel that is located in a region that tends to have high humidity during the summer. That means a necessary condition of installing radiant floor cooling is not high summer humidity. Or, contrapositively, if we’re in a hotel located in a region that tends to have high summer humidity, then no radiant floor cooling.

rf-cool → /region-high-sum-hum

Before looking at the answers, take stock of what conclusions are reachable. In general, we can run conditionals forward or contrapose backwards. Running them forward reaches the necessary conditions. Contraposing them backwards reaches the failure of the sufficient conditions. For these conditionals, that means there are four reachable conclusions:

rf-heat (either satisfying rf-cool or luxury)

/region-high-sum-hum (satisfying rf-cool)

/rf-cool (either failing rf-heat or failing /region-high-sum-hum)

/luxury (failing rf-heat)

It’s also important to take note of what conclusions are unreachable. That will help us quickly eliminate answers that are wrong on the basis of their logic alone. In general, affirmation of the necessary condition and the failure of the sufficient conditions are unreachable. Here, that means conclusions of rf-cool or /rf-heat are unreachable.

The first pair of answers I want to consider is Answer Choice (D) and Answer Choice (E). They both contain unreachable conclusions and hence are both wrong on the basis of their logic alone. Look at the conclusions in each. (D) concludes that the newest Bonjour hotel should have neither radiant floor heating nor radiant floor cooling. The “/rf-heat” portion of the conclusion is unreachable. (E) concludes just the opposite, that it should have both. The “rf-cool” portion of the conclusion is unreachable.

The conditionals in the stimulus cannot possibly be used to arrive at those conclusions. We were not told the necessary conditions of having radiant floor heating. And because we weren't told those necessary conditions, we don't know what to fail in order to draw the conclusion that there should be no radiant floor heating. This is the same logic with regard to radiant floor cooling. We need to know what its sufficient conditions are. But the stimulus doesn't tell us what the sufficient conditions of having radiant floor cooling are. Therefore we don't know what we need to satisfy to trigger radiant floor cooling.

Now contrast with Correct Answer Choice (B). It concludes that the newest Bonjour hotel should have radiant floor heating but not radiant floor cooling, rf-heat and /rf-cool. Those are reachable conclusions. (B) says that the region has high humidity year-round. That means it has high humidity during the summer. That fails a necessary condition of rf-cool. (B) also says that the hotel will be luxury. That satisfies one of the sufficient conditions for rf-heat.

Answer Choice (A) and Answer Choice (C) don’t suffer from logic issues like (D) and (E). They both contain reachable conclusions: /rf-cool. We can reach that conclusion in two ways, either failing rf-heat or failing /region-high-sum-hum, meaning either saying that the hotel won’t have radiant floor heating or saying that the hotel will be in a region with high summer humidity. But (A) and (C) don’t do either.

(A) says it’s not newly constructed. That immediately kicks it out of the domain of the stimulus which is guidelines for newly constructed hotels.

(A) and (C) both say that they are not luxury, but that doesn’t trigger anything.

(C) also says the newest Bonjour hotel will have radiant floor heating. That also triggers nothing.

This is a PSA question.

The difficulty in this question is partially in the complexity of the argument. Where is the main conclusion? There’s also a sub-conclusion present! It’s also partially in the answers. Some of the principles on offer tempt us to react based on what we know to be true or false in the world. But if we cut through these difficulties, this is a straightforward PSA question with a straightforward PSA answer: P→C.

First, the ranger says it’s unfair to cite people for fishing in the newly restricted areas. Okay, why? Because the people are probably unaware of the changes in the rules. Okay, why do you say that? Because many of “us rangers” are even unaware of the changes in the rules. So here’s the complex argument.

Minor premise: Many rangers are unaware of the new rules.

Major premise/sub-conclusion: Park visitors are probably unaware of the new rules.

Main conclusion: Unfair to cite visitors for violations.

But there’s one more pesky sentence at the end that says until after we really try to publicize these new rules, the most we should do is to issue a simple warning. How does this fit in? Maybe this is the main-main conclusion? Perhaps. It’s unfair to give citations, therefore issue a warning instead. That makes sense. Maybe this is the second half of the main conclusion? Park visitors aren’t aware of the new rules, therefore don’t cite them (negative), just give a warning (positive). That makes sense too. The conclusion is an injunction with a positive and negative component. Either way you interpret the last statement will be just fine. Something ambiguous like this won’t form the basis of the right/wrong answers. So, for simplicity, I’ll just interpret this to be part of the main conclusion.

Minor premise: Many rangers are unaware of the new rules.

Major premise/sub-conclusion: Park visitors are probably unaware of the new rules.

Main conclusion: Unfair to cite visitors; instead, give warnings.

Before we look at the answers, note that there are two places for us to PSA the support. We can bridge the minor premise to the sub-conclusion or we can bridge the major premise to the main conclusion. What would those bridges, in our own words, look like?

Minor descriptive-P → descriptive-C bridge: If some rangers are unaware of the new rules, then probably visitors are unaware.

Major descriptive-P → prescriptive-C bridge: If visitors are unaware of the new rules, then they should only be given a warning.

Correct Answer Choice (A) supplies the major descriptive-P → prescriptive-C bridge. It says that people should not be cited for violating laws of which they are unaware. If unaware, then should not be cited. Granted, it doesn’t “justify” the “simple warning” bit of the conclusion but this is a PSA question, after all, and not an SA question. The bar isn’t set so high as to require validity.

If you eliminated (A), ask yourself why. I don’t know, but might it be because (A) runs against what you know to be true in the world? Our legal system has a principle that ignorance of the law is no excuse. Yet (A) contradicts this principle. Is that why you were repelled by (A)?

Answer Choice (C) pretends to supply the minor P→C bridge. It says that the public should not be expected to know more about the law than any law enforcement officer. That lowers the bar for what the public “should be expected to know” all the way down to the knowledge possessed by the least-informed officer. So if any officer is unaware of the new regulations, then the public should not be expected to be aware either. On the face of it, this is appealing. The minor premise says some rangers aren’t aware, and with this principle, we can conclude that the public should not be expected to be aware. But wait a second, the sub-conclusion isn't prescriptive. It isn’t about what the public should or should not be expected to know. It’s a factual, probabilistic, descriptive statement about what the public does or does not know. To justify the minor support structure, we needed a descriptive-P → descriptive-C bridge.

But it’s appealing because we “like” this principle. We think it’s right. We think it’s just. But ask yourself, even if this principle is true, where does it get us? It gets us to the position that the public shouldn’t be expected to know about the new regulations. Okay. Then what? Does that mean they also therefore should be cited? That depends on whether ignorance of the law is an excuse. So you’re back to (A) anyway.

Answer Choice (B) says regulations should be widely publicized. Okay, so publicize them. But what should we do in the meantime? Should we cite or merely warn violators? (B) is embarrassingly silent.

Answer Choice (D) puts the burden on the public. It says that people who fish in a public park should make every effort to be fully aware of the rules. Where does this principle get us? That if there’s some lapse in knowledge about the rules, then it’s squarely on the shoulders of the public? That doesn’t help justify the conclusion.

Answer Choice (E) is a principle that affords violators the right to explain themselves, a right to a defense. Okay, calm down. Nobody is talking about a trial here. We’re just trying to figure out if a warning is enough or if a citation is warranted. It doesn’t matter what the violator has to say about how they view the regulations and whether they think it applies to them.

The author also assumes there isn’t another explanation for the assumed decrease in pass rate.

A

treats a phenomenon as an effect of an observed change in the face of evidence indicating that it may be the cause of that change

B

uses a lack of evidence that the quality of the Institute’s plumbing instruction has increased as though it were conclusive evidence that it has decreased

C

concludes that something has diminished in quality from evidence indicating that it is of below-average quality

D

uses a national average as a standard without specifying what that national average is

E

confuses a factor’s presence being required to produce a phenomenon with the factor’s presence being sufficient in itself to produce that phenomenon

This is a Flaw/Descriptive Weakening question.

The stimulus begins with a premise about a “new experimental curriculum” that a plumbing school has been using “for several years.” Then it says that a survey last year found that only 33% of the school’s graduates passed the certification exam, and that 33% is not good because the national average is “well above” that. Those are the premises. From those premises, the conclusion claims that the new curriculum has “lowered the quality of plumbing instruction.”

What?

Where did we encounter a decrease in the quality of plumbing instruction? We only have one static data point. We need at least two data points to show change. What was the pass rate last year and the year before? Was it higher? If it was higher than 33%, then maybe instruction has declined. But if it was lower, then maybe instruction has improved. That’s a major issue in this argument.

The only evidence we have from the argument, the results of the exam, shows that there’s something subpar about the plumbing school. It likely has something to do with the quality of the instruction. But there could also be other causal forces at work. Maybe its students. Maybe the school was severely damaged last year in a catastrophic fire.

Okay, so if you spot the weakness, you’re almost there. You still have to jump over the hurdle of the abstractly worded answers.

And it starts with the worst offender, Answer Choice (A). Just look at it. It says the argument is flawed because it treats a phenomenon as an effect of an observed change in the face of evidence indicating that it may be the cause of that change. The quick way to eliminate (A) is to recognize that this is a cause-effect confusion flaw, a commonly recurring flaw in LR. But it’s not what’s happening here, as we discussed above. The mistakes here are (1) confusing static (no change) with dynamic (change) and (2) misattributed cause.

The slow and thorough method involves lassoing the abstract language in (A) to the tangible concrete language in the stimulus. How do we do that? We can begin by looking at “treats a phenomenon as an effect of an observed change.” What is the argument treating as an effect? The decreased quality of plumbing instruction. So that must be the phenomenon. And it’s treating that as the effect of “an observed change,” which must be the adoption of the new curriculum. But wait, is that really a “change?” The curriculum has been in place for several years already. This is already looking to be descriptively inaccurate.

Let’s keep going. How about “in the face of evidence indicating that decreased quality of plumbing instruction may be the cause of adoption of the new curriculum”? What evidence? This is also descriptively inaccurate. The only evidence we have from the stimulus is that something isn’t up to snuff about the school. There’s no evidence that the school saw a sharp drop in its quality of instruction and then decided that they needed to fix this by adopting a new curriculum.

Answer Choice (B) says that the argument uses a lack of evidence that the quality of the school’s plumbing instruction has increased as though it were conclusive evidence that it has decreased. No, it doesn’t. It’s true that there is a lack of evidence of increase. But that’s not what the argument uses. The argument uses the presence of static evidence, the 33% pass rates, as if it were evidence of change. Also descriptively inaccurate.

Correct Answer Choice (C) can, fortunately, be analyzed in terms of premise descriptor and conclusion descriptor. It says that the argument “concludes that something has diminished in quality…” and indeed this is descriptively accurate. The argument concludes that the plumbing instruction has decreased in quality. “From evidence indicating that [plumbing instruction] is of below-average quality.” This is an accurate description of the premises. The evidence is the 33% pass rates. Does that indicate that plumbing instruction is of below-average quality? Not definitively, as I already noted above, but evidence doesn’t have to be definitive. And this is evidence of poor instruction. (C) also captures the move from static (low-quality instruction) to dynamic (decreased quality) that’s at the heart of this bad argument.

Answer Choice (D) says that the argument uses a national average as a standard without specifying what that national average is. This is true! Descriptively accurate! But it doesn’t matter because the argument isn’t weak for failing to specify just how many percentage points below the national average is “well below.” Imagine if the argument had told us what the national average was. Say it was 50%. The school’s pass rate is 33%, which is “well below.” Okay, is the argument better now? No. Because that was never the issue. Imagine again that the national average was 75%. The school’s pass rate is 33%, again “well below.” Is the argument better now? Or is the argument even substantively different now? No and no, because it doesn’t matter precisely how much below is “well below.”

Answer Choice (E) says that the argument confuses a “required” factor with a “sufficient” factor. This is the classic sufficiency-necessity confusion. That’s the oldest mistake in the book. That’s not what’s happening here. We’d have to do major reconstructive surgery on the argument for (E) to be right. We’d have to argue that the quality of a school’s curriculum is essential in the improvement of their graduates' pass rates on the national exam. Therefore, a school can expect to see improvements in pass rates simply by adopting a quality curriculum. That would be mistaking a necessary factor with a sufficient factor.

Zahler Motors executive: The Graham Motor Company should stop running its deceptive minivan commercial, which claims that Graham’s minivan has a foldable third-row seat while our minivans do not. Zahler’s minivan from the newest model year, which recently began arriving at dealers, has a foldable third-row seat.

Graham Motor Company executive: Our commercial is not misleading. Zahler dealers are still selling new minivans from the previous model year, which lack a foldable third-row seat.

Summary

Zahler Motors executive: The Graham Motor Company should not run its deceptive minivan commercial. Why? Because the commercial claims that Graham’s minivan has a foldable third-row seat and Zahler’s do not. Actually, our newest model of mini van does have a foldable third-row seat.

Graham Motor Company executive: Graham’s commercial is not misleading. Zahler is still selling older minivans that lack a foldable third-row seat.

Strongly Supported Conclusions

It is not misleading to claim that a product has a feature that a competing product lacks in some cases.

A

It is not misleading for a company to advertise that its product has a feature that a competing product lacks if some instances of the competing product that are currently offered for sale lack the feature in question.

This answer is strongly supported. Graham argues the commercial is not misleading solely because there are some minivans being sold by Zahler that do not have a third-row seat.

B

It is not misleading for a company to advertise that its product has a feature that a competing product lacks if company executives are unaware that the competing product has the feature in question.

This answer is anti-supported. The Graham executive is aware that there are some instances the competing product has the feature in question. Graham’s argument is that not all minivans sold by Zahler have this feature.

C

It is not misleading for a company to advertise that its product has a feature that a competing product lacks if most consumers would not choose the product solely or primarily on the basis of whether it has that feature.

This answer is unsupported. We don’t know what features are deciding factors for consumers.

D

It is misleading for a company to advertise that its product has a feature that a competing product lacks if, on balance, the competing product has more of the features that most consumers want.

This answer is unsupported. We don’t know what features most consumers want.

E

It is misleading for a company to advertise that its product has a feature that a competing product lacks if all instances of the competing product that are currently offered for sale have the feature in question.

This answer is anti-supported. Not all of the minivan Zahlers sell have the feature in question according the the Graham executive.

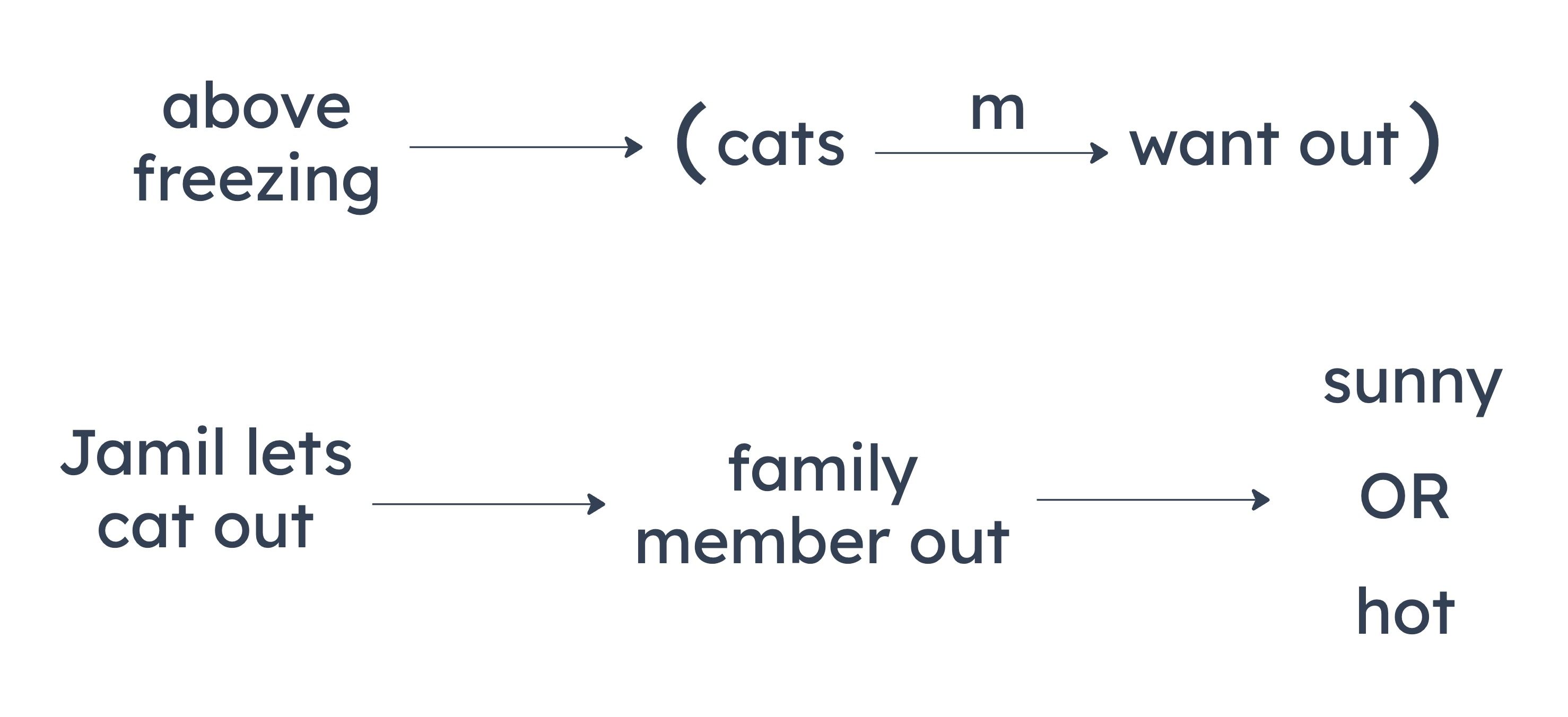

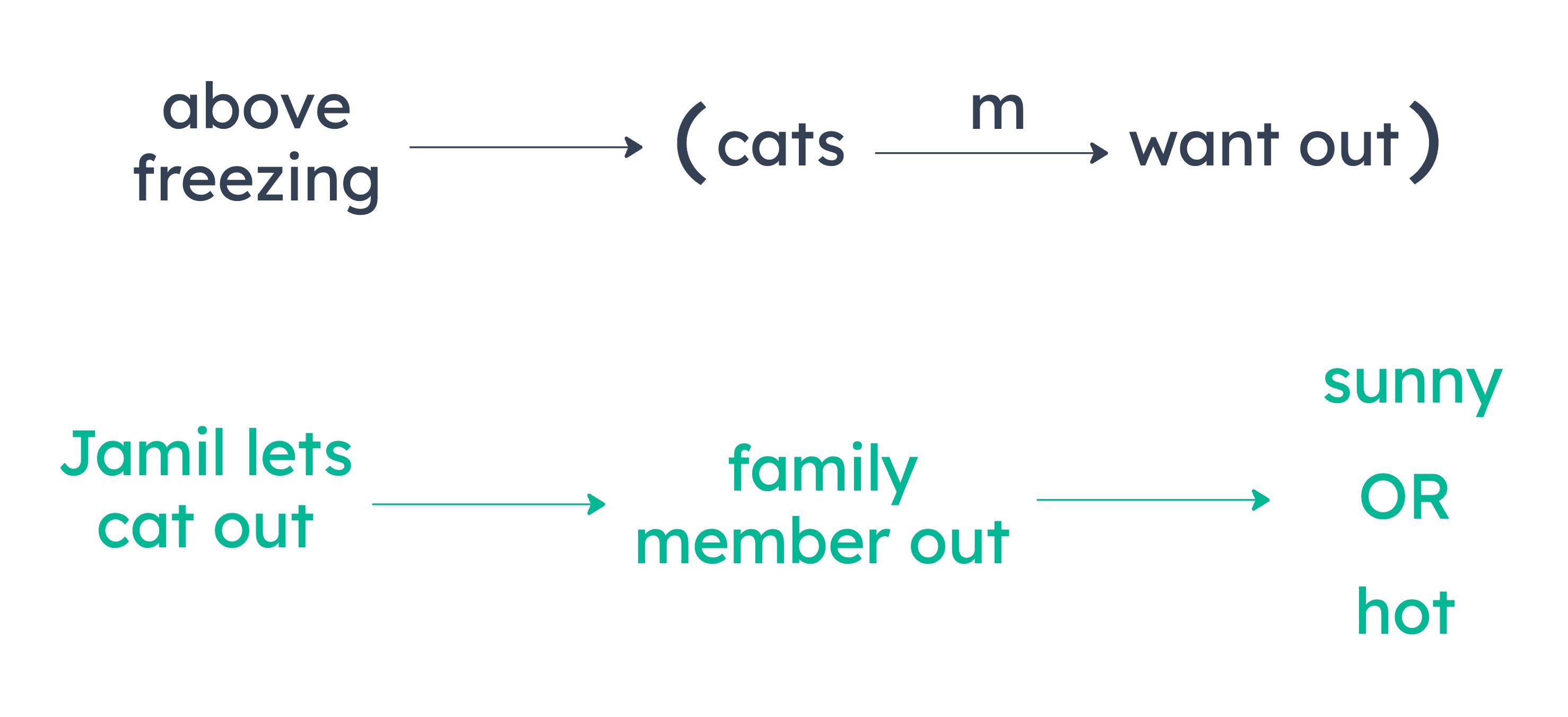

If Jamil lets his cat go outside, then at least one of his family members is outside.

If any of Jamil’s family members are outside, then it’s sunny or hot outside.

If it’s not sunny and it’s not hot, Jamil’s cat is not outside.

If Jamil lets his cat out, then it’s sunny or hot.

A

If Jamil’s cat is outside, then the temperature is above freezing.

B

If Jamil’s cat is not outside, it is cloudy and it is not hot outside.

C

If the sun is shining or it is hot outside, Jamil’s cat is probably outside.

D

If at least one member of Jamil’s family is outside, then Jamil’s cat is outside also.

E

If the sun is not shining and it is not hot outside, Jamil’s cat is not outside.

This is an Inference question. The question stem says “properly inferred.”

This question contains two sets of information, one of which is irrelevant and the other of which is what generates the inference. This question is actually closer to an MSS question than an MBT question. This is rare. Most questions that contain “inferences” in the stem are logically tight. This question is conspicuously an exception.

The stimulus states that “most cats like to go outside to play when the temperature is above freezing.” Translating this statement into logic, notice the conditional indicator "when" and the quantifier "most." For conceptual simplicity, let's kick the sufficient condition up into the domain. We are now talking strictly within the domain of when the temperature is above freezing. Under that domain, we are saying that of the set of cats, most of them like to go outside to play. Again, all of this is under the domain of when the temperature is above freezing. Now, as it turns out, and there's no way you could know this beforehand, this statement is completely irrelevant. The only way you’ll realize this is when you consider the answers. None of them make use of this statement.

The next statement creates a conditional chain from which we infer the correct answer. We are now talking about a specific cat. Jamil does not allow his cat to go outside unless at least one member of his family is outside. Translating this unless statement, we get the conditional that if Jamil's cat is allowed to go outside, then at least one member of his family is outside. Next we learned that Jamil's family members go outside only when the sun is shining or it is hot outside. This conditional connects directly to the previous one. If at least one member of his family is outside, then it must be either that the sun is shining or it is hot or both:

J’s cat allowed outside → J’s fam member outside → sun or hot

Now we can run a contrapositive. If the sun is not shining and it is not hot outside, then no member of Jamil's family is outside, then Jamil's cat is not allowed to go outside.

Does that mean Jamil's cat is not outside? This is the space between a reasonable or “proper inference” versus a deductively valid, must be true inference. In order to draw the conclusion that Jamil's cat is not outside, we have to assume that if Jamil's cat is not allowed to go outside, then it is not outside. This assumption is what Correct Answer Choice (E) requires. The fact that this is the correct answer reveals that the test writers think “properly inferred” is a lower standard of proof than “must be true.” Or the test writers made a mistake, though that’s highly unlikely.

I said at the beginning that this question was unusual because the overwhelming majority of questions using the “properly inferred” standard deliver answer choices that meet the higher “must be true” standard. But just because the test writers tend to overshoot a lower bar doesn't mean that the bar has been raised. They are just overshooting what has always been and presently is a lower bar. This is the same lesson we draw from some easier Weaken questions where the correct answer is identical to the ideal answer. That’s just the test writers overshooting the bar. On harder Weaken questions, we see the correct answer requiring assumptions.

The more salient decision for you is strategy: what to do under timed conditions? How do you respond when you detect this gap? The same as you always do. You pick the best answer. Looking at the other answers will reveal that (E) is the best out of the bunch for having made the fewest assumptions.

Answer Choice (A) says if Jamil's cat is outside, then the temperature is above freezing. This answer makes exactly the same assumption that (E) makes, namely that if Jamil's cat is outside, then he was allowed outside. But in addition it makes a mistake in logic. If Jamil's cat is allowed to go outside, then either the sun is shining or it is hot outside or both. It's possible that the temperature is not above freezing because the sun could be shining.

Answer Choice (B) says if Jamil's cat is not outside, then something something. At this point you can stop reading because (B) makes a logical mistake, the oldest mistake in the book: sufficiency-necessity confusion. Jamil's cat not being outside can only be a necessary condition according to the chain we have above.

Answer Choice (C) makes the same logical mistake as (B): sufficiency-necessity confusion. The sun is shining or it is hot outside is at the tail end, the necessary condition end of the chain. You cannot start a sufficient condition with the sun is shining or it is hot outside. It leads nowhere.

Answer Choice (D) says if at least one member of Jamil's family is outside, then Jamil's cat is outside also. This answer also requires the same assumption that (E) requires. Notice it also says the cat is outside as opposed to Jamil's cat is allowed outside. Additionally, (D) makes a sufficiency-necessity confusion. If Jamil's cat is allowed to go outside, then at least one member of his family is outside, not the other way around.

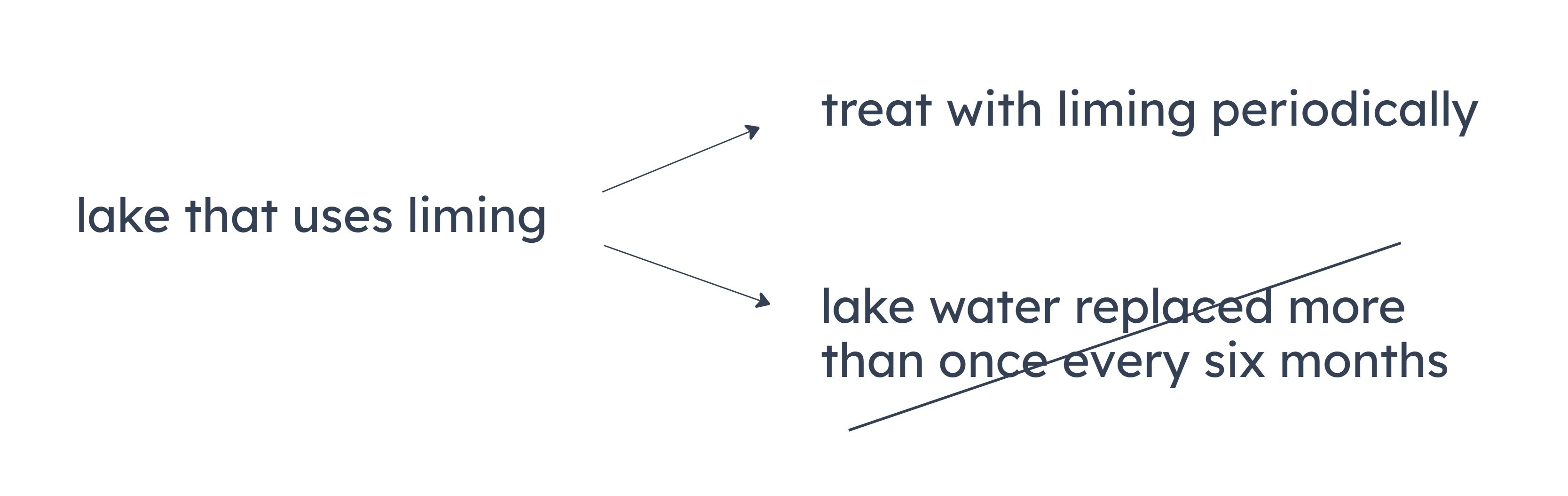

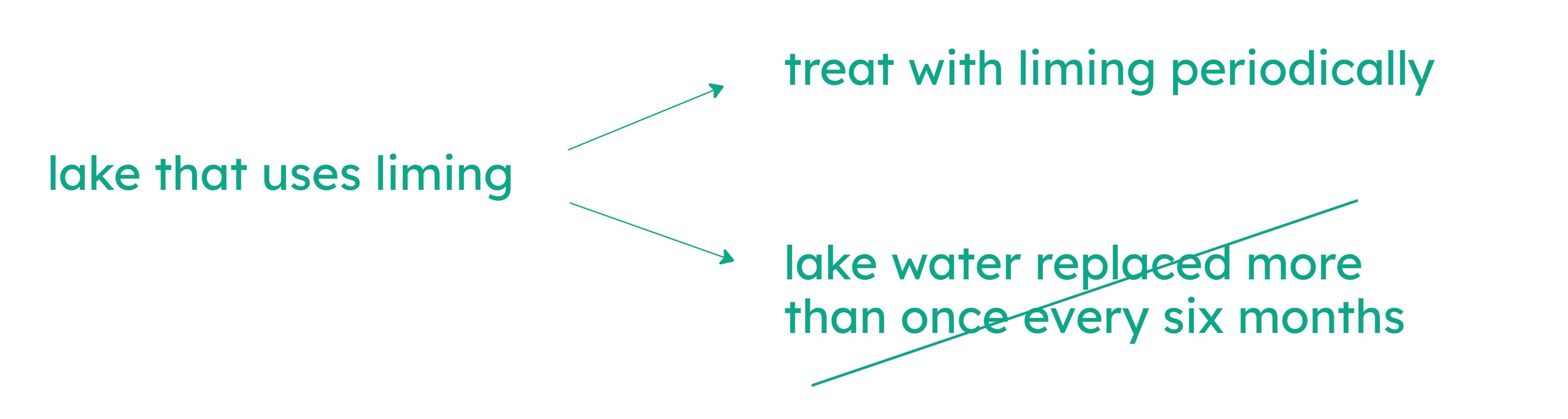

A

If a lake is a candidate for liming, its water is replaced every six months or less often.

B

In some lakes, if liming is to be successful over the long term in counteracting the harmful effects of acid rain, liming must be repeated at intervals.

C

Unlimed lakes in which the water is replaced frequently are less likely to be harmed by acid rain than those lakes in which the water is replaced infrequently.

D

Liming can be effective even if it is used after some life in a lake has been killed by acid rain.

E

If a lake’s water is replaced frequently, it may not be economical to attack the effects of acid rain there by liming.

Further Explanation

This is a Must Be True, Except question.

Four answers must be true on the basis of the information in the stimulus. The correct answer could be false.

The stimulus tells us that wildlife experts are adding lime to water to counteract the harmful effects of acid rain. How exactly does lime help? First, it neutralizes acid and thus prevents some damage. Second, it also helps to restore the health of some lakes where life has already been damaged by acid. Note the causal language, not that this affects the correct answer.

Next, specific details about this treatment. If a lake is treated with lime, this treatment must be periodic. That’s a conditional claim. Why? Because water in the lake is constantly being replaced and that has the effect of carrying away whatever lime we put in there. That’s a causal claim. How periodically? That we don't know. But we are told that if a lake's water is replaced more than once every six months, then we're not going to use lime because it's too expensive. That's another conditional claim followed with a causal explanation. This makes sense because the more frequently water in the lake is replaced, the more frequently we have to add lime to it. The lakes where the water is being replaced more than once every six months are apparently too expensive.

Answer Choice (A) says if the lake is a candidate for liming, its water is replaced every six months or less often. This must be true. This is simply the contrapositive of the last statement in the stimulus. Note that negation of “more often than once every six months” is “once every six months or less frequently.”

Answer Choice (B) says in some lakes, if liming is to be successful over the long term in counteracting the harmful effects of acid rain, liming must be repeated at intervals. This also must be true for it is simply a restatement of a conditional from the stimulus. The stimulus states lakes in which lime is used must be treated “periodically,” which just means “repeated at intervals.”

Correct Answer Choice (C) states unlimed lakes in which the water is replaced frequently are less likely to be harmed by acid rain than those lakes in which water is replaced infrequently. This is simply an appeal to our common sense. It is entirely unsupported by the information in the stimulus and therefore could be false. We know from the stimulus that acid rain damages lakes. We also know that adding lime helps to protect and restore those lakes. (C), however, talks about unlimed lakes. It tries to compare two different kinds of unlimed lakes, one where the water is replaced frequently versus the other where the water is replaced infrequently. (C) says the former is less likely to be harmed by acid rain. Again, no information above supports this statement. But our common sense wants to say this is true because we think that if water gets replaced, it should carry the acid away as well, which should be better for the health of the lake. That sounds reasonable and it may in fact be true in the world. But that is irrelevant. The question stem asked for valid support from the statements in the stimulus.

Answer Choice (D) says liming can be effective even if it is used after some life in a lake has been killed by acid rain. This must be true. It is simply what it means to “restore the health of some lakes where life has already been harmed by acidification.”

Answer Choice (E) says if a lake's water is replaced frequently, it may not be economical to attack the effects of acid rain there by liming. This also must be true. Depending on how frequently, it may in fact not be economical. And we know exactly how frequently because the stimulus tells us: more than once every six months.

A

A lack of regular exercise is one cause of lethargy in North Americans.

B

High consumption of fast food is a health risk only when combined with a lack of regular exercise.

C

The researcher’s data show that the consumption of fast food is not the main cause of poor health in North Americans.

D

The lethargy studies failed to consider one probable cause of lethargy.

E

The researcher’s conclusion was not adequately justified by the lethargy studies.

Transportation official: I reject the claim that the ruts in our city’s roads are caused by large trucks rather than studded snow tires. There are many places that have as much large truck traffic as we have here and also have a comparable amount of snowfall, and only those few places that allow studded snow tires have ruts in their roads similar to ours. Clearly, studded snow tires are to blame.

Summarize Argument

The transportation official concludes that studded snow tires, rather than large trucks, cause the ruts in the city’s roads. She supports this by saying that many other places have just as much large truck traffic and snowfall as her city, but only those that allow studded snow tires have similar ruts in their roads.

Notable Assumptions

The transportation official assumes that other factors, such as the presence of large trucks, are not also contributing to the ruts. She blames only studded snow tires without considering that they might be causing the ruts in conjunction with some other factor.

A

Large trucks are not allowed to have studded snow tires in many areas.

We don’t know if “many areas” includes the transportation official’s city or any of the other cities that she references. Because of this, (A) is too vague to strengthen her conclusion.

B

The number of ruts in the roads of the transportation official’s city has declined recently as the amount of large truck traffic has diminished.

This weakens the argument by pointing out another factor that could be contributing to the ruts in the roads. If the ruts decrease as large truck traffic decreases, it’s more likely that large trucks also contributes to the ruts in the roads.

C

Most of the places that allow studded snow tires but have negligible large truck traffic have roads full of ruts similar to those in the transportation official’s city.

This strengthens the argument by eliminating another possible cause of the ruts. If places with studded snow tires but negligible large truck traffic also have similar ruts in the roads, then the large truck traffic is likely not contributing to the ruts.

D

Some cities with even more truck traffic than in the transportation official’s city also have ruts in their roads.

The transportation official’s argument blames studded snow tires for the ruts, and we don’t know whether the cities mentioned in (D) also have studded snow tires. Thus, (D) is irrelevant.

E

Most places that have little snowfall do not allow the use of studded snow tires.

Irrelevant— the transportation official’s argument only addresses those places that do allow the use of studded snow tires and the effects of those tires on the roads.

A

Bookstore customers are more likely to purchase a book that they have seen on a best-seller list than one that they have not.

B

In the 1990s, bookstore customers’ most frequent purchases were books written by authors who had already written at least one best-seller.

C

In the 1990s, less commercial, more literary works increasingly had their initial publication in paperback editions rather than hardback editions.

D

By 1996, there were about 20 percent more titles in print than in 1986.

E

Books that are not expected to be best-sellers are featured more often in independent bookstores than in book megastores.

A

Life forms that have a different effect on the ratio of S-34 to S-32 from that of life forms on Earth could have evolved elsewhere.

B

The effects of life on the ratio of S-34 to S-32 depend on a number of climatic and environmental factors with regard to which Earth and Mars differ.

C

The ratio of S-34 to S-32 in the meteorite is the same as that on Mars as a whole at the time that the material in the meteorite left Mars.

D

Relatively few terrestrial mineral samples contain S-34 and S-32 in the ratio that indicates the presence of biological activity.

E

The current ratio of S-34 to S-32 on Mars is different from that at the time the material in the meteorite left Mars.

Further Explanation

This is a Weaken Except question, so that means four answers cut against assumptions that the argument made.

Usually when you see a Weaken Except question, that means the argument is especially bad because how else can there be so many assumptions for the answers to contradict? This argument is no exception. It really is bad. And it's bad for having made two different types of assumptions. This can be difficult to recognize. Another difficulty is the use of jargon and the reference to ratios. If it's one thing that LSAT students don't like, it's scientific jargon and math. Both are present here.

The first sentence states a causal relationship that occurs on Earth. On Earth, biological activity leads to, i.e., causes, a change in the ratio. So this is my advice about how to overcome the hurdle of jargon and also incidentally the hurdle of “math.” They don't matter. They don't matter because the rest of the argument and all the answer choices consistently reference the same “ratio.” So who cares what the ratio is called? All we need to focus on is the causal relationship, which is that biological activity causes a change in the ratio.

The next sentence tells us that a newly discovered meteorite, a rock, from Mars exhibits ratios found only in terrestrial minerals dating from before the beginning of life on Earth. The sentence takes a bit of parsing to understand. First, you have to understand that terrestrial minerals mean rocks on Earth. So, in other words, the ratio we find in this rock from Mars is similar to the ratio we find in rocks from Earth before there was life on Earth.

Now we get to the conclusion. The author concludes that it's unlikely life occurred on Mars.

I already said there are two different types of assumptions here. One is the assumption of analogy. This argument relies on reasoning by analogy because it assumes that the causal relationship on Earth of biological activity causing a change in the ratio would also be present on Mars. Would it? Mars and Earth are different places and those differences could mean that this causal relationship isn’t analogous. This is what Answer Choice (A) and Answer Choice (B) point out.

Answer Choice (B) says the effects of life on the ratio depend on a number of climatic and environmental factors with regard to which Earth and Mars differ. This is a very straightforward way of disanalogizing Earth and Mars. (B) tells us that biological activity isn't the only cause that's involved in the alteration of the ratio. Other causes matter too, like climatic and environmental factors, and those factors are different between Mars and Earth. So the ratio found in the Mars rock may not indicate the absence of life on Mars after all.

Answer Choice (A) is more subtle than (B) but also works on the argument’s reasoning by analogy. It says life forms that have a different effect on the ratio from that of life forms on Earth could have evolved elsewhere. This means that we shouldn't assume that Earth life forms’ effects on the ratio is universal. That means it's possible that different kinds of life forms could have evolved elsewhere and that those extraterrestrial life forms could have had a different effect on the ratio. This is an indirect way of suggesting that Mars and Earth are disanalogous. (A) is suggesting that if life had evolved on Mars, it's possible that Martian life would have had a different effect on the ratio.

Of the four answers that weaken the argument, these are the two that cut against the argument’s use of reasoning by analogy. They point out dissimilarities between Earth and Mars. (B) does this specifically and explicitly. (A) does this indirectly by suggesting that Earth and other places in general may be crucially dissimilar.

The other two answers that weaken the argument do so by cutting against a different assumption. That’s the assumption that the single Martian rock tells us something about the state of the Martian planet. If you think about it, it might occur to you that Mars is a big place and the meteorite is quite small by comparison. Is it true that the properties of that single rock reveal something about the entire planet? Well, that all depends on what properties of the rock we’re talking about and what characteristics of the planet we’re trying to figure out. In some ways, surely this rock is representative of Mars. But don't assume that it is representative of Mars in all ways. This is what Answer Choice (D) and Answer Choice (E) point out.

Answer Choice (E) says the current ratio on Mars is different from that at the time the meteorite left Mars. That means the ratio in the rock is not representative of the ratio on Mars today. That means this rock is not evidence of what has happened on Mars since it left the planet. Has life evolved in the intervening time? It’s unclear. (E) severely undermines the relevance of the only piece of evidence on which the conclusion is based by declaring the evidence to be chronologically unrepresentative.

Answer Choice (D) says that relatively few terrestrial mineral samples (rocks we find on Earth) contain ratios that would indicate the presence of life. This is a subtler way of calling out the representativeness of the rock from Mars. (D) says that if we looked at the ratios of rocks on Earth, we would find no signs of biological activity. Yet we know there is obviously plenty of biological activity on Earth. Therefore, this method of reasoning, that is, using the ratio found in rocks, is a poor way of figuring out whether there is life on Earth. This suggests that using this kind of reasoning might also lead to a faulty conclusion for Mars. I'm careful to say “suggests” because I recognize that this (meta) argument itself depends on an analogy between Mars and Earth. The crucial similarity assumed is that just like on Earth, even if there was biological activity on Mars, most of the rocks on Mars would not reflect that activity. That means there’s a good chance that this sample, this only piece of evidence we have, would also fail to capture the effects of life on Mars.

As you can see from the way these answers are structured, (B) and (E) are the more explicit refutations of the two assumptions in the argument. (A) and (D) are the subtler counterparts. They merely suggest that the assumptions are questionable.

Correct Answer Choice (C) says the ratio in the rock from Mars is the same as that on the planet as a whole at the time that the rock left Mars. This doesn't hurt the argument. This helps the argument, though only a little. Now we can be sure that this rock was representative of the ratio on Mars as a whole at some point in time. It doesn't guarantee that it's still representative of the ratio on the planet in the intervening time, as (E) points out, but it does at least partially patch up the issue of representativeness.