This is an NA question.

The stimulus proceeds in order from premises to the conclusion. Bovine remains were found in a certain place back when that place had an arid (dry) climate. There were people present at that time in that region but no other large mammals. If there were natural sources of water available, there would also have been other large mammals. But we already know there were no other large mammals. We can contrapose to infer that there were no natural sources of water available.

The argument hence concludes that these bovines had been domesticated (people were providing it water) and the people there were no longer exclusively hunter-gatherers.

This sounds like a decent argument, right? If you think so, then you’re already supplying the missing assumption, that if they weren’t domesticated, they couldn’t have survived. But really, we don’t know that. Perhaps they were wild and crafty and survived by taking advantage of man-made water sources. That would be bad for the argument. So we do need to supply the assumption connecting the premises (arid climate, no natural water sources) to the conclusion (domestication).

This is what Correct Answer Choice (A) does. Translating the “unless,” (A) says that if the bovines weren’t domesticated, they were unlikely to exist in a region without natural sources of water. The premises fail the necessary condition (the bovines likely did exist), which allows us to infer the failure of the sufficient condition (the bovines were domesticated) as the conclusion. This connects the premises to the conclusion. More than that, it truly is necessary. If we deny this conditional relationship, we’re asserting that it’s possible for the bovines to be wild yet survive anyway in this arid region. That’s exactly the possibility that we contemplated above that would ruin the argument.

Answer Choice (B) says that domesticating animals is one of the first things that a society must do when transitioning from hunter-gatherer to agriculture. This is unnecessary. Why first? Why not second or third? Also notice that it’s trying to bridge the two concepts in the conclusion, that of “domestication” and that of “no longer exclusively hunter-gatherer.” But we don’t need to build that bridge. They are already connected by their definitions. Domestication necessarily implies no longer exclusively hunter-gatherer. A culture that practices domestication cannot be exclusively hunter-gatherer.

Answer Choice (C) says that other large mammals would have been able to inhabit this arid region with the help of humans. So, like what? Horses? That’s required? No, it’s not. Let’s imagine this were false. Even with the help of humans, this arid region could not have supported horses. Who cares? The argument is still as strong as it ever was.

Answer Choice (D) says no human culture can be a hybrid of agriculture and hunter-gatherer. So (D) is claiming that all human cultures must be exclusively either an agricultural society or else a hunter-gatherer society. You can’t do both. But that’s silly. It doesn’t affect the argument if there was a culture that both planted wheat and hunted meat. In fact, the conclusion in the stimulus claims that these people are a kind of hybrid culture.

Answer Choice (E) says that a domesticated cow doesn’t need as much water as a wild cow. This might strengthen the argument? Like their modest demand for water might help explain why humans were able to domesticate them in an arid climate. But it’s not necessary. Imagine this were false and the cows required the same amount of water, regardless of whether they were domesticated or wild. The argument would still be fine. It would just have been not as easy to domesticate them.

This is an NA question.

The argument begins with a pretty long sentence that turns out to be just context. It tells us similarities between the “chorus” in a play and the “narrator” in a novel. They share many similarities. Both introduce a point of view untied to other characters. Both allow the author to comment on the characters’ actions and to introduce other information.

With the word “however,” we transition from context to argument. And it’s a simple argument with one premise and one conclusion. The premise is that the chorus sometimes introduces information inconsistent with the rest of the play. The conclusion is that the chorus is not equivalent to the narrator.

What’s the missing link? It’s a premise-to-conclusion bridge. We have to assume that the narrator never introduces inconsistent information.

This is what Correct Answer Choice (D) provides. It says that information introduced by a narrator can never be inconsistent with the rest of the information in the novel. That’s it. And with this assumption, the argument is valid. This is an example of where a necessary assumption is also a sufficient assumption. This tends to happen when the argument structure is simple and therefore there is only one assumption to bridge the premise to the conclusion.

Answer Choice (A) is attractive. It says the narrator is never deceptive. This sounds necessary, right? Because the premise said the chorus was deceptive and so in order for the narrator to not be equivalent with the chorus, it must be that the narrator is never deceptive. But no, this isn’t necessary. The premise just said that the chorus sometimes introduces information that’s inconsistent with the rest of the play. That doesn’t mean the chorus is being deceptive. We’re projecting intent onto the chorus without evidence. Maybe they’re trying to deceive. Maybe they’re trying to help us see through the deception of a character in the play. The chorus is telling the truth to the character’s lies. So no, (A) is not necessary. The narrator can be deceptive and the conclusion can still follow that the narrator is not equivalent to the chorus.

This also explains why Answer Choice (E) is unnecessary. (E) claims that authors sometimes use choruses to mislead audiences.

Answer Choice (B) says the voice of a narrator is sometimes necessary in plays that employ a chorus. What? Get out of here with this basic BS. This is just a mish-mash of ideas from the stimulus. There’s no reason why a play that employs a chorus must also employ a narrator.

Answer Choice (C) claims that information necessary for the audience to understand the events in a play is sometimes introduced by the chorus. No, this isn’t necessary. Let’s say that all the information introduced by the chorus is “extra” information: nice to have but not required for the audience to understand the play. What impact would that have on the argument? Not much. The narrator can still be not equivalent to the chorus as long as the narrator does what (D) says.

This is an NA question.

The stimulus opens with context that the premises call upon with a referential phrase. To establish a human colony on Mars, it requires the presence of a tremendous quantity of basic materials on Mars. And then we need to assemble those materials. The premise states that the costs of transporting those materials through space would be very high. Therefore, the argument concludes that it wouldn’t be economically feasible to establish a colony on Mars.

The assumption is that the costs in the premises are a consideration that matters. What are those costs again? Costs of “transporting material through space.” Now, why would we need to transport materials through space? Because a Martian colony requires a tremendous amount of basic materials. But again, why must we transport that “tremendous amount of basic materials” through space? The assumption is that those materials cannot be found on Mars.

This is absolutely necessary for the premises to even matter to the conclusion. This is what Correct Answer Choice (E) says. That Mars isn’t a practical source of the basic materials required for establishing human habitation there. If Mars were, then there’d be no need to transport those materials through space.

(E) seems pretty obvious once you get there. But the hard part is in getting past the other trap answers.

Answer Choice (A) is one such trap. It uses “only if” to lay out a necessary condition for establishing human habitation on Mars: the decrease in cost of transporting materials from Earth to Mars. This sounds good but it isn’t necessary. First, note that the conclusion didn’t claim that it would be physically impossible to colonize Mars. Rather, just that it would be economically infeasible. Economically infeasible means highly unlikely, but it doesn’t mean impossible. Economic constraints are softer than physical or technological constraints. Economic constraints are a matter of collective resource allocation. Physical or technological constraints are imposed by what knowledge we have access to. Second, note that the premises cited the costs of transportation through space. Surely Earth to Mars is through space but so is the moon to Mars. And so is the asteroid belt to Mars. If the materials aren’t even coming from Earth in the first place, then why should we care about the transportation costs of Earth to Mars?

Answer Choice (B) is another trap. It says that the cost of transportation through space (note already the improvement upon (A)) isn’t expected to decrease in the near future. Again, this sounds good. Don’t we need the costs to not decrease? Well, first notice that (B) isn’t about what will actually happen to the costs. It’s about what we expect to happen to the costs. We don’t need expectations to point in any particular direction. We need actual costs to not decrease. Second, even if actual costs decrease in the near future, the argument can still survive as long as the costs don’t decrease too much. For example, imagine if the costs decrease by 0.01%. That’s presumably not enough of a decrease to make a difference. In order to hurt the argument, we need to have the costs decrease to the point of being economically feasible to transport enough basic materials to Mars.

Answer Choice (C) claims that Earth is the only source of basic materials necessary for a Martian colony. This is a classic Strengthen answer in an NA question. If (C) were true, then that definitely helps the argument. Earth is the only source of raw materials and therefore, to get those materials to Mars, we must transport them through space. But this isn’t necessary. What if one of Mars' two moons had the requisite materials? That would still require transportation through space and so the argument would still survive. (C) isn’t necessary.

Answer Choice (D) says that no significant benefit would result from establishing a human colony on Mars. This isn’t necessary. The argument didn’t express a value judgment. It wasn’t about the pros and cons of establishing a Mars colony or whether we should do it. It was just an argument about the costs and economic feasibility of such an endeavor. (D) is not only unnecessary, it is also irrelevant.

This is an NA question.

This is a very difficult argument to understand substantively. Let’s first approach this question by breaking it up into its parts. Conveniently, it progresses in order from minor premise to major premise to main conclusion. The two conclusion indicator words “thus” and “therefore” help us recognize this.

There may be a way to get to the right answer without fully understanding the argument substantively, but I wouldn’t bank on it. You’ll have to pick up in the main conclusion the new reference to “other characteristics.” What other characteristics? We’ve only talked about a star’s brightness. So the “other characteristics,” whatever they may be, had better be determinable.

If you picked up on that, then you’re probably down to Answer Choice (B) and Correct Answer Choice (D). The problem with (B) is that it’s too specific and hence unnecessary. We don’t need “differences in the elements each is burning” to be detectable from Earth. We just need some difference to be detectable from Earth, like how (D) has it.

Okay, but let’s back up and try to actually understand this argument.

The minor premise tells us that the distance between Earth and a distant galaxy overwhelms the distance between Earth and any object in that distant galaxy. Imagine you’re on a tiny island and we’re trying to measure the distance between you and two people on a different faraway tiny island. They’re not equidistant from you. One of them is actually closer, because, say, one is standing at the shore and the other is standing on the other side of the island. But the first sentence is saying that the distance between the two islands is so vast that that’s the only thing that really matters. The islands themselves are so small and the vast space between the islands so large that it hardly matters where anyone is standing on their islands. That difference is so small that it’s negligible.

So it follows that if two stars are in the same distant galaxy (two people on the same distant island), then the distance between those two stars to Earth will in effect be the same (because whatever difference is negligible). But if we still observe a difference in their brightness, that difference can’t be due to their (negligibly different) distance. It must be due to their actual brightness as in how bright they’re actually burning and not just how bright they appear to be.

Now the argument reaches for its main conclusion. It concludes that we should be able to figure out the correlation between two stars' relative actual brightness and the two stars’ other characteristics. We see “other characteristics” appear out of nowhere. We did talk about brightness and how if two stars are in the same distant galaxy, we can in effect treat them as being equidistant from Earth in terms of their brightness. But in order to correlate their brightness with “other characteristics,” we first have to be able to detect and measure those “other characteristics.”

Again, this is what Correct Answer Choice (D) picks up on. It says that there are stars in distant galaxies that have characteristics, other than brightness, discernible from Earth. This must be true. If this were false, that would mean that we could discern only a distant star’s brightness and nothing else. If that’s true, then we would be unable to correlate brightness with anything else.

Note that (D) doesn’t care to specify what the “characteristics” are. That’s good because the conclusion didn’t care to specify either. This is what makes Answer Choice (B) unnecessary. While (B) would certainly strengthen the argument, we don’t need the differences in the elements each is burning to be detectable from Earth. Who knows what “other characteristics” the conclusion wanted to correlate with brightness? Maybe it’s the elements that each is burning. Maybe it’s the color of the stars, their size or mass, or their temperature. It could be any of those characteristics that need to be detectable from Earth.

Answer Choice (A) says that if two stars are in two different galaxies... Eh, we can stop. We don’t care. The argument cares about two stars in the same distant galaxy. (A) talks about two stars in two different (near or far?) galaxies. Whatever else (A) is about to say for these two stars will be irrelevant so you should move on to the next answer.

But for review, we can negate this and see that it has no impact on the argument. So what if it is possible to determine their distances from Earth? That doesn’t hurt the argument.

Answer Choice (C) is similarly irrelevant for it talks about stars in our own galaxy. Again, for the same reasons as in (A), we don’t care. We should move on.

If we negate (C), that’s just fine for the argument. It would be absolutely bizarre if all the stars in the Milky Way were all approximately the same distance from Earth but it wouldn’t affect the argument.

Answer Choice (E) can also be similarly eliminated as soon as you see that it’s talking about stars that are significantly different in distance from Earth. The argument contemplated two stars that are not significantly different in distance from Earth. That’s what the sub-argument established by placing the two stars in distant galaxies to begin with. We should move on.

(E) goes on to say that if there are significant differences in how far away two stars are from Earth, then those stars will differ significantly in apparent brightness. This isn’t required. It’s fine for the argument if two stars of significant difference in distance from Earth are about the same in brightness. The argument contemplated two stars of insignificant difference in distance but significant difference in brightness. After all, a major assumption of the argument is that distance is only one factor in determining a star’s brightness.

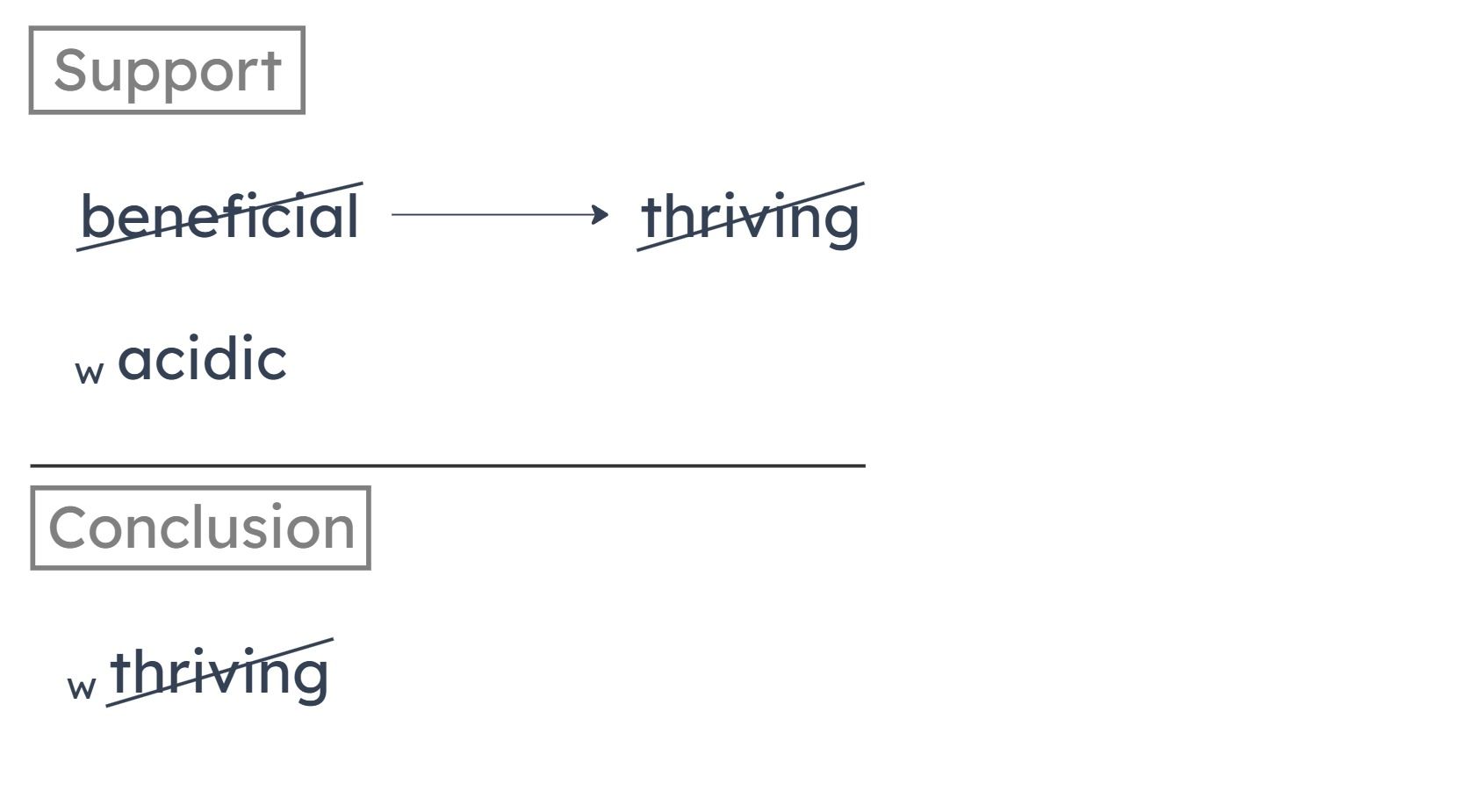

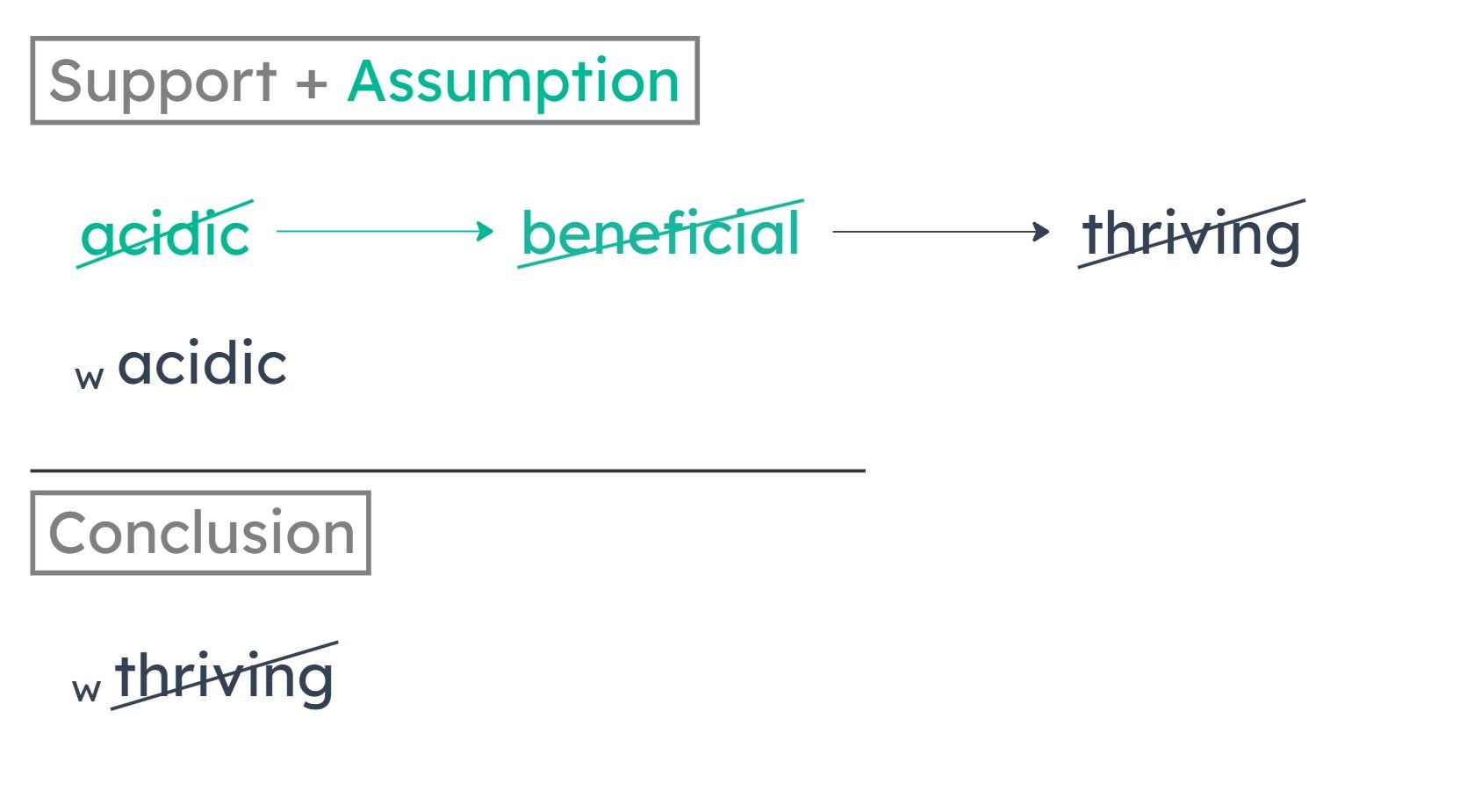

In order to have a thriving population of turtles in a pond, conditions in the pond must be beneficial to turtles.

The water in Wallakim Pond is acidic.

Do we have enough to prove that? No...the other premise simply states that Wallakim Pond is acidic. But is an acidic pond something that does NOT benefit turtles? We don’t know. To make the argument valid then, we want to establish that an acidic pond is a condition that does NOT benefit turtles.

A

If the water in a pond is not acidic, the conditions at that pond are beneficial to turtles.

B

The most important factor that determines whether a pond will have a thriving turtle population is the acidity of the water.

C

The water conditions at Sosachi Pond are more beneficial to turtles than are the water conditions at Wallakim Pond.

D

Wallakim Pond would have a thriving population of turtles if it were not acidic.

E

The conditions at a pond are beneficial to turtles only if the water in the pond is not acidic.

This is a Sufficient Assumption question.

The argument starts with a conditional: a thriving population of turtles in a pond requires beneficial conditions at the pond.

thriving → beneficial

Wallakim Pond, we’re told, has acidic water.

acidicw

We’re also told that Sosachi Pond doesn’t but the conclusion doesn’t care about Sosachi and so we shouldn’t either.

Finally, the conclusion says that the population of turtles at Wallakim Pond must not be thriving.

/thrivingw

Let’s put this all together.

thriving → beneficial

acidicw

_________________

/thrivingw

Looking at the conclusion, you can see that the argument is trying to contrapose on the conditional. It’s trying to fail the “beneficial” condition. If it’s successful in doing that, then we can conclude “/thriving.” But the problem is that the only other premise doesn’t hook up to “/beneficial.” We don’t know what “acidic” means for turtles. Is that beneficial for them or not? If we’re able to establish that “/acidic” is a necessary condition, then this argument becomes valid:

thriving → beneficial → /acidic

acidicw

_________________

/thrivingw

This is what Correct Answer Choice (E) gives us. It says that the conditions of a pond are beneficial only if the water is not acidic. That’s exactly what we’re looking for: beneficial → /acidic.

Answer Choice (A) says that if the water is not acidic, then the conditions are beneficial. /acidic → beneficial. That’s the sufficiency-necessity confused version of (E).

Answer Choice (B) says that the acidity of water is the most important factor that determines whether the population of turtles will be thriving. But that doesn’t tell us whether acid is good or bad. It just says it’s powerful. In which direction? Even if (B) said that it’s in the bad direction, it would merely strengthen the argument, which would still fall short of the SA requirement.

This is what we in effect get in Answer Choice (C). It says that the conditions at Sosachi are more beneficial than the conditions at Wallakim. We have to assume that all other conditions are held equal between Sosachi and Wallakim. On that assumption, we can infer that the difference is caused by the difference in their waters’ acidity. But even then, it just means that acidity is relatively less beneficial.

Answer Choice (D) says that Wallakim would have a thriving population if the water were not acidic. That translates to /acidic → thriving. But that doesn’t fit what we’re looking for.

That means it’s the acidity in the water that’s causing the population to not be thriving.

This is a PSA question.

The argument begins with the conclusion that some of the rare pygmy bears should be moved from their native island to the neighboring island. Naturally, we wonder why. The rest of the argument supplies the premises. First, we learned that they are at risk of extinction owing to habitat loss. Second, we learned that the neighboring island is the only place that has a similar habitat. Hence, moving them is the only viable chance of saving them from extinction. That's a sub-conclusion/major premise. The main conclusion is the first sentence. We should move them.

This PSA question is just like most other PSA questions. The argument presents a P and arrives at a C. Our job is to find in the answers a P → C rule or bridge.

We can say something like if an action is the only viable method of saving an endangered species, then we should take that action. Keep in mind that PSA answers can be stated very specifically or very generally. Overinclusiveness is not a problem for this question type.

Correct Answer Choice (C) gets the job done. It says if a species is in danger of extinction, whatever is most likely to prevent the extinction should be undertaken. The premises trigger the sufficient condition because the rare pygmy bears are explicitly said to be at risk of extinction. The conclusion satisfies the necessary condition. Moving them to the neighboring island is the only viable chance and therefore it is the most likely way to prevent extinction. Therefore, it should be undertaken.

Answer Choice (B) can be eliminated on the basis of its logic alone, as is commonly the case for wrong answers on PSA questions. It says rare animals should not be moved from one habitat to another unless these habitats are similar to one another. This stipulates a necessary condition on the movement, not a sufficient condition on the movement. That's a problem for us because the conclusion wants to move these animals. Do the Group 3 translation on the logical indicator “unless.” If the habitats are not similar to one another, then the animals should not be moved. Satisfying the sufficient condition here only allows us to draw the conclusion that these animals should not be moved.

Answer Choice (E) can be eliminated because it's too weak. It's better than (B) in the sense that there is no logical issue. It says if an animal's original habitat is in danger of being lost, then it is permissible to try to find a new habitat for the animal. That's fine, the premises satisfy the sufficient condition, which allows us to draw the conclusion that it is permissible to try to find a new habitat for the pygmy bears. But that doesn't mean we should do it. Permissible doesn't imply should. This is too weak.

Answer Choice (A) says some species are more deserving of protection than other species. This is a truism. Which species are more deserving of protection than others? We don't know. Even if we did, what manner should the protection take? Again, we don't know.

Answer Choice (D) says the rarer a species of plant or animal is, the more that should be done to protect that species. This allows us to draw conclusions about preservation priorities. If we know that the rare pygmy bear is rarer than, say, the panda bear, then according to (D), we should afford priority and do more to protect the pygmy bears. But how is this relevant to the argument? We’re not concerned about whether we're doing too much or too little for the pygmy bears in comparison to some other endangered species.

The question stem says of the following judgments, which one most closely conforms to the principle above? This is a rarer type of question though we have seen it plenty before. They're asking us to take the principle in the stimulus which is a conditional statement and push it into the arguments in the answers to see where it fits. But that’s like a PSA question. Instead of the stimulus containing an argument searching for a conditional in the answer, it's the other way around. The stimulus contains a conditional searching for an argument. This is a cosmetic difference.

The stimulus lays down two jointly sufficient conditions for justified governmental interference with an individual’s actions. The two conditions are:

- The action would increase the likelihood of harm to others; and

- The action is not motivated by a desire to help others.

If both conditions are met, then the government is justified in interfering with the individual’s action.

As an aside, note that these two conditions each cover a different kind of consideration. The first looks at the consequences of the action. Will this action harm others? The second looks at the intent of the action. What motivated the action? In general, considerations of morality tend to fall into these two buckets of consequences and intent.

Back to the task at hand. Given that this is a PSA question, it’s important to note which conclusions are reachable and which are unreachable.

A reachable conclusion is that the government is justified in interfering with the individual’s action. To reach this conclusion, we just have to show that (1) and (2) are satisfied.

An unreachable conclusion is that the government is not justified in interfering with the individual’s action. There’s simply nothing we can show to trigger the conditional in that way. If we wanted to reach the unjustified conclusion, we need to know what the necessary conditions of justified are, fail those conditions, then contrapose back.

This analysis is helpful in eliminating Answer Choice (A). It tries to conclude that the government is unjustified in interfering with Jerry’s moviemaking. We don’t need to read the rest of the argument. There’s nothing that the premise can state that will make use of the conditional to reach this conclusion. (A) is therefore wrong on its logic alone. In other words, it makes a sufficiency-necessity confusion, the oldest mistake in the book. We can stop here, but for review, look at the premise. It says that Jerry’s action (moviemaking) doesn’t harm and won’t increase the likelihood of harming anyone. It also says that it is motivated by a desire to help others. So it fails both (1) and (2). But failing sufficient conditions just makes the rule go away. It doesn’t trigger anything. Yet, (A) thinks it triggers the failure of the necessary condition. That’s textbook sufficiency-necessity confusion.

Contrast this with Correct Answer Choice (E). It concludes that the government is justified in preventing Jill from giving her speech. That’s a reachable conclusion. We just need to show that Jill’s speech satisfies (1) and (2). And it does. Her speech “would most likely have caused a riot and people would have gotten hurt.” That’s physical harm to others. And her speech was “to further her own political ambitions.” That’s a selfish motivation and hence not a motivation to help others.

Answer Choice (B) concludes that the government is justified in fining the neighbor for not mowing his lawn. That’s a reachable conclusion. We just need to show that the neighbor’s not mowing his lawn satisfies (1) and (2). (1) is problematic. It’s not pleasant to look at an unkempt lawn, but that’s not physical harm to others. We don’t need to consider (2) but probably the neighbor’s decision to not mow his lawn was selfishly motivated. He was probably just feeling lazy.

Answer Choice (C) concludes that the government is justified in requiring motorcyclists to wear helmets. That’s a reachable conclusion. We just need to show that motorcyclists’ not wearing helmets satisfies (1) and (2). Again, we have a problem for (1). It’s not clear that their failure to wear helmets would increase harm to others, whatever the consequences of harm are for themselves. We don’t need to consider (2) but probably their decision to not to wear helmets was selfishly motivated. They probably were feeling lazy, wanted to look cool, or have a death wish.

Answer Choice (D) concludes that the government is justified in suspending Z’s license to test new drugs. That’s a reachable conclusion. We just need to show that Z’s testing new drugs satisfies (1) and (2). Again, we have a problem for (1). It’s not clear that their testing of new drugs would increase harm to others. In fact, if they’re a drug company, then it’s more likely that their testing of new drugs would do just the opposite. It would help others alleviate pain and suffering. We don’t need to consider (2) but here the argument makes explicit that their motivation is selfish and not to help others.

A

Some strains of honey produced by bees harvesting sage nectar are unusually high in antioxidants.

B

Most plants produce nectar that, when harvested by bees, results in light-colored honey.

C

Light-colored honey tends to be more healthful than dark honey.

D

Certain strains of honey produced by bees harvesting primarily sage nectar are unusually low in antioxidants.

E

The strain of honey that has the highest antioxidant content is a light-colored honey.

Further Explanation

This is a Most Strongly Supported question.

The stimulus provides two different types of information. First, we’re given a correlation, which turns out to be useless. Second, we’re given a logical chain, which is what produces the inference.

The correlation is that darker honey tends to be higher in antioxidants than lighter honey.

The next piece of information, even though it's still in the same sentence, expresses a different relationship. It says that all of the most healthful strains of honey are unusually high in antioxidants. The keyword is “all” which the test writers conveniently hid in the middle of the sentence. If you catch that, you can translate this into an all statement using the conditional arrow. The set of “the most healthful strains of honey” is completely subsumed under the set of “honey that's unusually high in antioxidants”:

most healthful → unusually high in antioxidants

Finally, we learned that there are some strains of honey that come from sage nectar and are among the lightest in color, yet are also among the most healthful. This is a “some relationship,” an overlap in two sets. One of the sets is what we've already talked about: the set of the most healthful strains of honey. The other is the set of honey that comes from sage nectar and is lightest in color.

sage and among lightest ←s→ most healthful

We can chain together this “some statement” and the previous “all statement”:

sage and among lightest ←s→ most healthful → unusually high in antioxidants

This is a commonly repeating valid argument form A ←s→ B → C which produces the valid inference A ←s→ C. Translated back into English, some of the lightest strains of honey produced by bees harvesting sage nectar are unusually high in antioxidants. This is what Correct Answer Choice (A) says. Almost. (A) drops “lightest” but that’s fine. If it’s true that some of the lightest sage honey is X, then it’s also true that some sage honey is X.

Answer Choice (B) says most plants produce nectar that results in light-colored honey. This is unsupported. The information in the stimulus is consistent with most plants producing dark-colored honey or light-colored honey.

Answer Choice (C) says light-colored honey tends to be more healthful than dark honey. This is not supported (or actually, a bit anti-supported). All we know is that darker honey tends to be high in antioxidants. We also know that the most healthful honeys are all unusually high in antioxidants. This weakly suggests that it's the antioxidants that are causally responsible for the healthful effects. If we take that to be true, then (C) is actually anti-supported. But we don’t have to because this is just an MSS question and being unsupported is good enough to eliminate this answer.

Answer Choice (D) says certain strains of honey produced by bees harvesting primarily sage nectar are unusually low in antioxidants. This is unsupported. It’s a tempting answer because we know that sage nectar produces “among the lightest strains of honey” and we also know that there is a general correlation between honey being light and it having less antioxidants. But we also have enough information to infer that sage is an exception to the correlation, because we know that sage-produced light honey is among the most healthful strains of honey and we further know that the entire set of the most healthful strains of honey is subsumed under the set of honey that is unusually high in antioxidants.

Answer Choice (E) says the strain of honey that has the highest antioxidant content is a light-colored honey. This is unsupported. It could be true but it also could be false. We only have information in the stimulus about the set of honey that is among the lightest or among the most healthful or is unusually high in antioxidants. We have no information about the specific strains of honey at any of the extremes of those spectrums.

Many sociologists oppose this theory. They oppose this theory based on the premise that a complex phenomenon — such as the popularity of political parties — cannot be caused by a simple phenomenon.

A

economically motivated decisions by voters need not constitute a complex phenomenon

B

a complex phenomenon generally will have many complex causes

C

political phenomena often have religious and cultural causes as well as economic ones

D

popular support for political parties is never a complex phenomenon

E

the decisions of individual voters are not usually influenced by their beliefs about which policies will yield them the greatest economic advantage

This is an Inference question.

The question stem says “properly inferred” from the sociologist's perspective. Inference from others' perspective is a question type that we see more often in RC.

The stimulus starts by telling us what rational choice theory says about what causes support for political parties. It says that popular support for political parties is caused by individual voters making deliberate decisions to support those parties whose policies they believe will economically benefit them. In other words, individuals' beliefs about the economic consequences of a particular party's policies cause those individuals to support those parties. This causal relationship is what is meant by “sufficiently explained.”

But the sociologists don't agree. They oppose rational choice theory on the premise that a complex phenomenon like the rise of a political organization or party cannot be caused by a simple phenomenon.

What is this “simple phenomenon”? It must be the individual voters making economic decisions to support political parties, which implies that it must not be a complex phenomenon. This is what Correct Answer Choice (A) says. Sociologists believe that economically motivated decisions by voters need not constitute a complex phenomenon. We are getting hints of an NA question. Note how (A) could have stated this much more strongly. Economically motivated decisions by voters constitute a simple phenomenon. That would have been correct as well. But the test writers took it one step further and stated an inference of that statement.

Answer Choice (B) says a complex phenomenon generally will have many complex causes. This is unsupported. The sociologists only said that a complex phenomenon cannot be caused by a simple phenomenon. This leaves open several possibilities. Perhaps they believe that a complex phenomenon can be caused by many simple phenomena. Or perhaps they believe that a complex phenomenon can be caused by a single complex phenomenon. We’d have to dismiss those alternatives without warrant in order to arrive at (B).

Answer Choice (C) says political phenomena often have religious and cultural causes as well as economic ones. This is even more unsupported. Note the same reasoning in (B) applies here. Additionally, (C) draws an inference to religious and cultural causes on the basis of nothing.

Answer Choice (D) says popular support for political parties is never a complex phenomenon. This is anti-supported. The sociologist called the rise of a political organization a complex phenomenon. Within the context of the stimulus, the rise of the political organization is synonymous with popular support for a political party.

Answer Choice (E) says the decisions of individual voters are not usually influenced by their beliefs about which policies will yield them the greatest economic advantage. This is unsupported. The stimulus talks about a narrow political relationship. It examines the causes of the rise of popular political parties. (E) talks about a much broader political relationship, the causes of individual voting decisions. The stimulus has very little to say about what generally causes (influences) or doesn't cause voters to cast their vote one way or another.

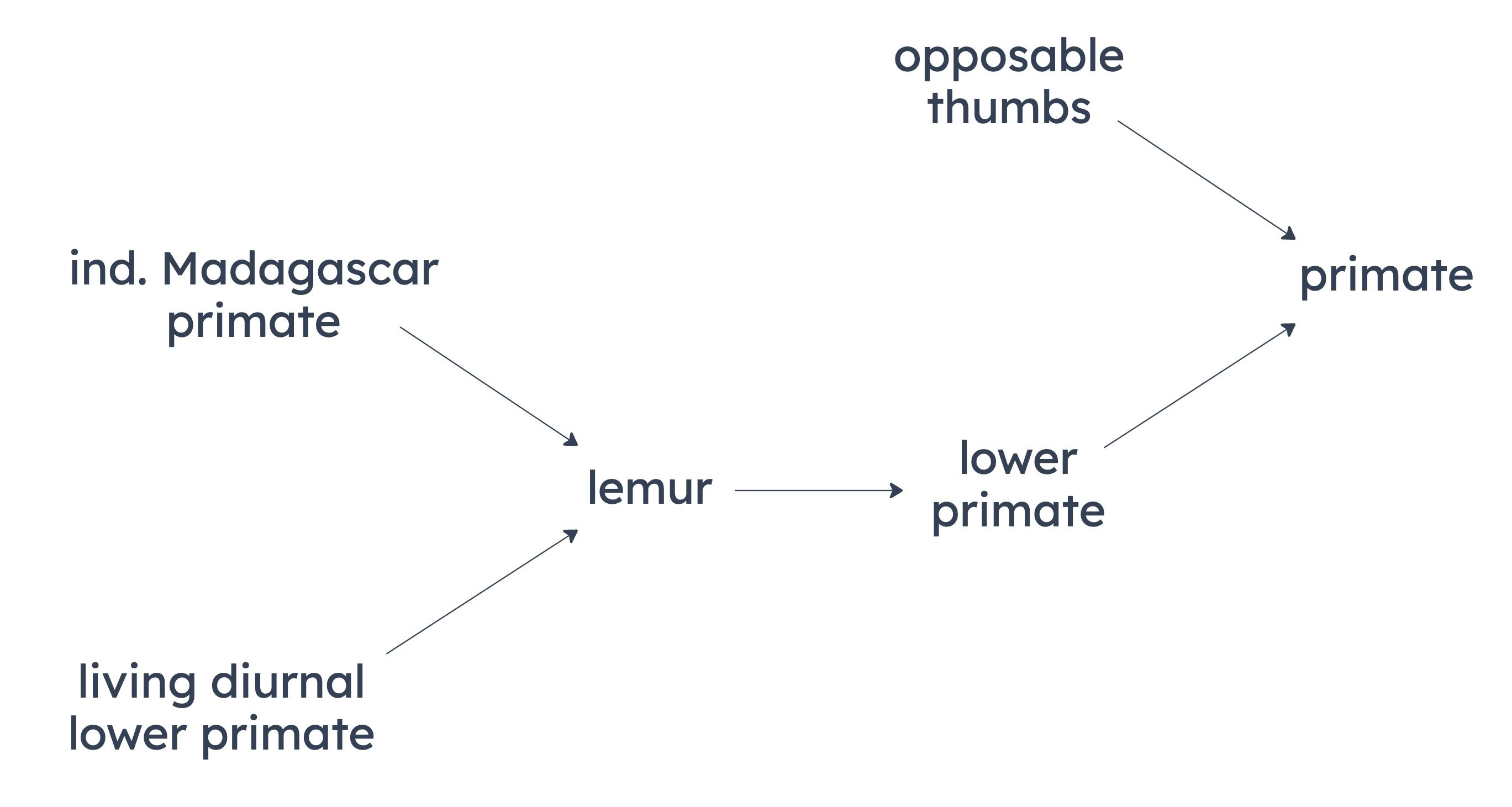

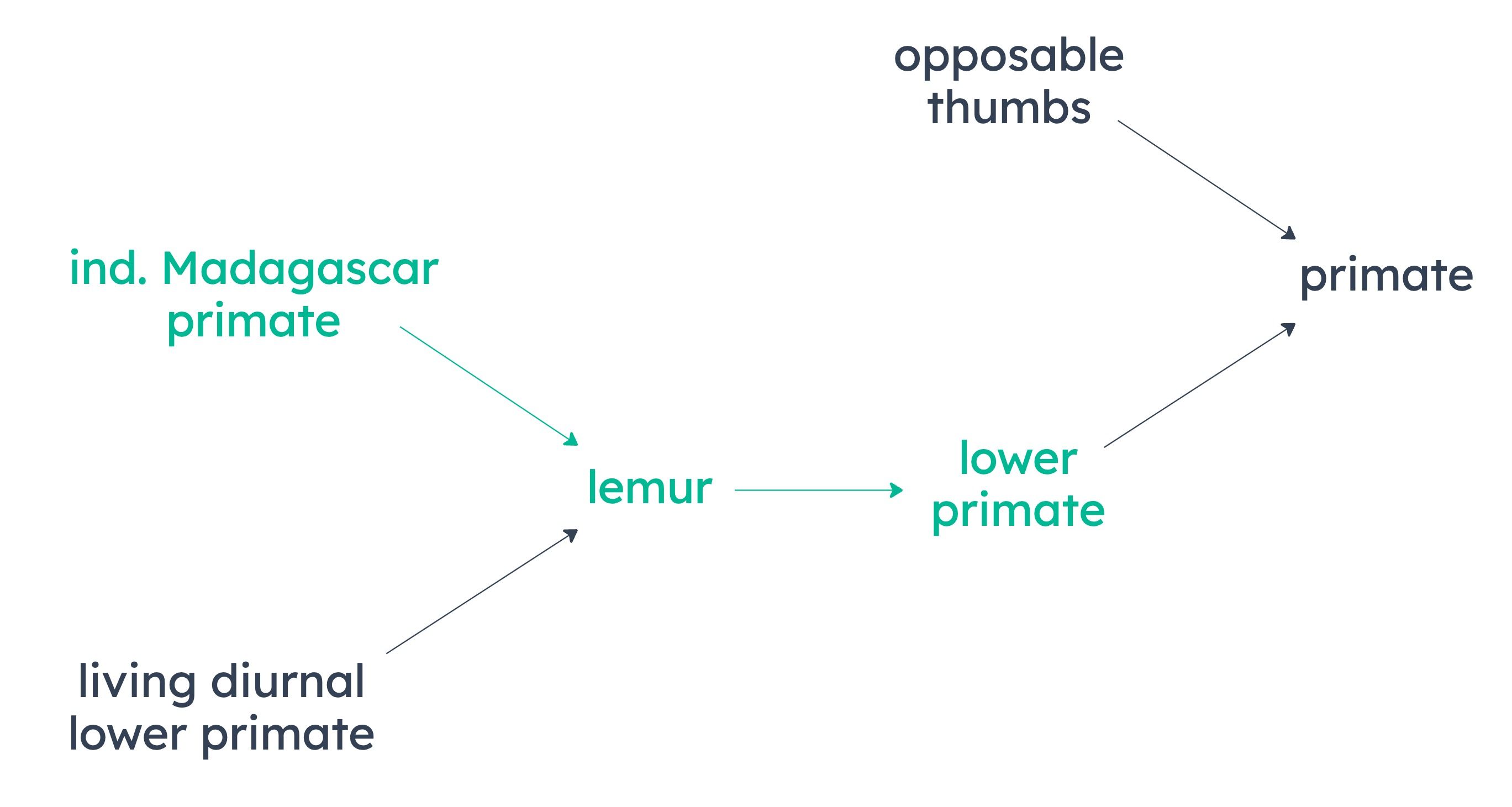

The only primates indigenous to Madagascar are lemurs.

Lemurs are lower primates.

Some lemurs are the only living diurnal lower primates.

All higher primates are thought to have evolved from a single diurnal species of lower primate.

All living diurnal lower primates are lemurs.

A

The chimpanzee, a higher primate, evolved from the lemur.

B

No primates indigenous to Madagascar are diurnal higher primates.

C

No higher primate is nocturnal.

D

There are some lemurs without opposable thumbs.

E

There are no nocturnal lemurs.

This is an Inference question.

The question stem says “properly inferred.” This is a challenging question because there is so much information in the stimulus that is all connected. That can easily induce panic as you scramble to draw all the connections and valid inferences. Strategically, you shouldn't do that. The more connected information a stimulus contains, the more valid inferences there are to be drawn, the less you are able to anticipate the correct answer choice. In stimuli like those, POE is the better approach.

The first line in the stimulus about the study of primates being interesting is the only irrelevant fact. Everything else is fair game.

Only primates have opposable thumbs. Lemurs are lower primates (a subset of primates.) And lemurs are the only primates indigenous to Madagascar. Some species of lemurs are the only living lower primates that are diurnal. They go ahead and define diurnal for us but the answer choices never swapped out the term for its definition so we don't need to pay attention to it. Finally, all higher primates (a subset of primates) are thought to have evolved from a single diurnal species of lower primates.

Lots of information. Let’s POE.

The last piece of information is what sets up the trap in Answer Choice (A). It says that the chimpanzee, a higher primate, evolved from the lemur. This is not a proper inference. This is unsupported. All we can say is that the chimpanzee, being a higher primate, is thought to have evolved from a single diurnal species of lower primates. Which one, though? Must it be the lemur because the lemur is a diurnal species of lower primates and it is the only living one? No. Being alive isn’t required. We’re talking about evolution here. Most ancestor species are extinct. There may well have been other extinct, diurnal species of lower primates. One of those extinct species may well be the evolutionary starting point of all higher primates.

Correct Answer Choice (B) says no primates indigenous to Madagascar are diurnal higher primates. We can transform this into the following logically equivalent claim: all primates indigenous to Madagascar are not diurnal higher primates. This must be true. The stimulus says that the only primates indigenous to Madagascar are lemurs and that lemurs are all lower primates. It is implied that lower primates cannot be higher primates, diurnal or otherwise. This is the conditional chain: prim-indig-M → lemur → low-prim

Answer Choice (C) says no higher primate is nocturnal. This is unsupported. We simply have no idea if higher primates are nocturnal or diurnal or anything else. The only piece of information we have about higher primates is that they are thought to have evolved from a single diurnal species of lower primates.

Answer Choice (D) says there are some lemurs without opposable thumbs. This is unsupported. The stimulus says only primates have opposable thumbs. That means if something is not a primate then it doesn't have opposable thumbs. But lemurs are primates. Sufficient condition failed, rule goes away.

Answer Choice (E) says there are no nocturnal lemurs. This is unsupported. The stimulus tells us that some species of lemurs are diurnal. Maybe all species of lemurs are diurnal, maybe not.