This is an NA question.

The argument begins with a pretty long sentence that turns out to be just context. It tells us similarities between the “chorus” in a play and the “narrator” in a novel. They share many similarities. Both introduce a point of view untied to other characters. Both allow the author to comment on the characters’ actions and to introduce other information.

With the word “however,” we transition from context to argument. And it’s a simple argument with one premise and one conclusion. The premise is that the chorus sometimes introduces information inconsistent with the rest of the play. The conclusion is that the chorus is not equivalent to the narrator.

What’s the missing link? It’s a premise-to-conclusion bridge. We have to assume that the narrator never introduces inconsistent information.

This is what Correct Answer Choice (D) provides. It says that information introduced by a narrator can never be inconsistent with the rest of the information in the novel. That’s it. And with this assumption, the argument is valid. This is an example of where a necessary assumption is also a sufficient assumption. This tends to happen when the argument structure is simple and therefore there is only one assumption to bridge the premise to the conclusion.

Answer Choice (A) is attractive. It says the narrator is never deceptive. This sounds necessary, right? Because the premise said the chorus was deceptive and so in order for the narrator to not be equivalent with the chorus, it must be that the narrator is never deceptive. But no, this isn’t necessary. The premise just said that the chorus sometimes introduces information that’s inconsistent with the rest of the play. That doesn’t mean the chorus is being deceptive. We’re projecting intent onto the chorus without evidence. Maybe they’re trying to deceive. Maybe they’re trying to help us see through the deception of a character in the play. The chorus is telling the truth to the character’s lies. So no, (A) is not necessary. The narrator can be deceptive and the conclusion can still follow that the narrator is not equivalent to the chorus.

This also explains why Answer Choice (E) is unnecessary. (E) claims that authors sometimes use choruses to mislead audiences.

Answer Choice (B) says the voice of a narrator is sometimes necessary in plays that employ a chorus. What? Get out of here with this basic BS. This is just a mish-mash of ideas from the stimulus. There’s no reason why a play that employs a chorus must also employ a narrator.

Answer Choice (C) claims that information necessary for the audience to understand the events in a play is sometimes introduced by the chorus. No, this isn’t necessary. Let’s say that all the information introduced by the chorus is “extra” information: nice to have but not required for the audience to understand the play. What impact would that have on the argument? Not much. The narrator can still be not equivalent to the chorus as long as the narrator does what (D) says.

This is an NA question.

The argument begins with a pretty long sentence that turns out to be just context. It tells us similarities between the “chorus” in a play and the “narrator” in a novel. They share many similarities. Both introduce a point of view untied to other characters. Both allow the author to comment on the characters’ actions and to introduce other information.

With the word “however,” we transition from context to argument. And it’s a simple argument with one premise and one conclusion. The premise is that the chorus sometimes introduces information inconsistent with the rest of the play. The conclusion is that the chorus is not equivalent to the narrator.

What’s the missing link? It’s a premise-to-conclusion bridge. We have to assume that the narrator never introduces inconsistent information.

This is what Correct Answer Choice (D) provides. It says that information introduced by a narrator can never be inconsistent with the rest of the information in the novel. That’s it. And with this assumption, the argument is valid. This is an example of where a necessary assumption is also a sufficient assumption. This tends to happen when the argument structure is simple and therefore there is only one assumption to bridge the premise to the conclusion.

Answer Choice (A) is attractive. It says the narrator is never deceptive. This sounds necessary, right? Because the premise said the chorus was deceptive and so in order for the narrator to not be equivalent with the chorus, it must be that the narrator is never deceptive. But no, this isn’t necessary. The premise just said that the chorus sometimes introduces information that’s inconsistent with the rest of the play. That doesn’t mean the chorus is being deceptive. We’re projecting intent onto the chorus without evidence. Maybe they’re trying to deceive. Maybe they’re trying to help us see through the deception of a character in the play. The chorus is telling the truth to the character’s lies. So no, (A) is not necessary. The narrator can be deceptive and the conclusion can still follow that the narrator is not equivalent to the chorus.

This also explains why Answer Choice (E) is unnecessary. (E) claims that authors sometimes use choruses to mislead audiences.

Answer Choice (B) says the voice of a narrator is sometimes necessary in plays that employ a chorus. What? Get out of here with this basic BS. This is just a mish-mash of ideas from the stimulus. There’s no reason why a play that employs a chorus must also employ a narrator.

Answer Choice (C) claims that information necessary for the audience to understand the events in a play is sometimes introduced by the chorus. No, this isn’t necessary. Let’s say that all the information introduced by the chorus is “extra” information: nice to have but not required for the audience to understand the play. What impact would that have on the argument? Not much. The narrator can still be not equivalent to the chorus as long as the narrator does what (D) says.

This is a Main Conclusion question.

The stimulus contains an argument with many complications. It starts with other people's argument. OPA is a causal argument moving from a correlational premise to a causal conclusion. The author responds to OPA by pointing out the possibility of an alternate cause. She does so by pointing out another correlation that wasn't considered by OPA. She concludes that OPA wasn't well reasoned.

First, we learned that North Americans are becoming more lethargic. In the third sentence, we find out that North Americans are also consuming more fast food meals. This is the correlational phenomenon which OPA—“one researcher”—uses to support his causal conclusion in the second sentence. OPA concludes that fast food has an adverse effect (casual) on people's health. Note the assumption that lethargy is bad for health.

The author begins her argument with “however.” The first thing she tells us is that few lethargic adults exercise regularly. This is introducing another correlation. OPA told us that lethargy is correlated with increased consumption of fast food. The author is telling us that lethargy is also correlated with less exercise. But more than that, the author says this correlation is actually causal because lack of exercise can contribute to lethargy.

Now we get to the author's conclusion, which is that OPA delivered a weak argument. The lethargy studies do not settle the question of whether fast food is unhealthy. In other words, the correlation between lethargy and fast food isn’t dispositive evidence that fast food causes lethargy and hence poor health. Why? Because an alternative explanation of the lethargy studies is available through its correlative and causal relationship with exercise.

Note that the last sentence of the stimulus is in fact the main conclusion and it has a conclusion indicator “thus” preceding it. This is a good reminder that shortcuts don't always work. In general, we’re better off focusing on the fundamentals rather than playing mind games with the test writers.

Answer Choice (A) is a premise of the author's argument.

Answer Choice (B) states something new and therefore cannot be the conclusion. It says that high consumption of fast food is a health risk only when combined with a lack of regular exercise. Given the information in the stimulus, I have no idea if that's true.

Answer Choice (C) says the researcher’s data show that the consumption of fast food is not the main cause of poor health in North Americans. This might be tempting, but this isn’t the main conclusion. There is a big difference between something not being the main cause versus not knowing whether something is the main cause. The author's conclusion is simply that whether fast food is unhealthy isn't settled by the lethargy studies. That's a much more modest claim than what's present in (C), which says that it is settled and we know definitively that fast food is not the main cause of poor health. That's not what the author was trying to say. The author pointed out exercise simply to reveal OPA's failure to consider alternative causes.

Answer Choice (D) says the lethargy studies failed to consider one probable cause of lethargy. This is not exactly right. The author criticizes OPA for failing to consider one probable cause of lethargy. Both the author and OPA use the lethargy studies as a starting point. Neither criticizes that study.

Correct Answer Choice (E) says the researcher's conclusion was not adequately justified by the lethargy studies. This is exactly right, and if you map the language from this answer onto the content of the argument, you get a correlation-causation flaw. The researcher's conclusion is that fast food causes lethargy. The lethargy studies are what supply half of the correlation between lethargy and fast food consumption. The author is simply saying that the correlation between lethargy and fast food doesn't adequately justify the conclusion that fast food causes lethargy.

A

A lack of regular exercise is one cause of lethargy in North Americans.

B

High consumption of fast food is a health risk only when combined with a lack of regular exercise.

C

The researcher’s data show that the consumption of fast food is not the main cause of poor health in North Americans.

D

The lethargy studies failed to consider one probable cause of lethargy.

E

The researcher’s conclusion was not adequately justified by the lethargy studies.

This is a Strengthen question.

The argument begins with a phenomenon that a certain ancient society burned large areas of land. Naturally, we wonder why they did this. The author presents other people's hypothesis: they burned large areas of land to prepare the ground for planting, which means that the ancient society was beginning the transition to agriculture.

To test this hypothesis, we can check its predictions. One prediction would be evidence of agriculture. If it's true that they burned the ground in preparation for planting, then we should expect to find evidence of agriculture. But we have little evidence of cultivation after the fires. This strongly implies that the other people's hypothesis of transition to agriculture is wrong. And so the author concludes it is likely that the society was still a hunter-gatherer society.

Now, one quick assumption you might've noticed is whether ancient societies fall into the binary buckets of either agricultural or hunter-gatherer. That is something to keep in mind, but as it turns out, those two buckets do largely capture all societies. The answer choices don't try to undercut that assumption.

But don't forget that we still have this phenomenon presented in the beginning argument. The author hasn't given an explanation of why the ancient society burned large areas of land. She has only, rather effectively, disposed of a bad explanation.

This is where Correct Answer Choice (D) improves the reasoning of the argument. It says hunter-gatherer societies are known to have used fire to move animal populations from one area to another. This presents a plausible explanation of the phenomenon unexplained in the original argument. If this is true, then that phenomenon itself becomes support for the author's conclusion that the society was still a hunter-gatherer society.

Answer Choice (A) says many ancient cultures had agriculture before they began using fire to clear large tracts of land. This means that fire clearing of land is not necessary for the transition to agriculture. That's good to know if you were curious about early human civilization. But this has nothing to do with the argument. The fact is the particular ancient society we’re talking about did clear large areas of land with fire. We’re trying to figure out what that means about the status of their civilizational development.

Answer Choice (B) says hunter-gatherer societies use fire for cooking and for heat during cold weather. This doesn't affect the argument at all. The argument told us that this particular society used fire to burn large areas of land and then we try to argue that this particular society was still a hunter-gatherer society. Information about hunter-gatherer societies using fire to do other things doesn't help the claim.

Answer Choice (C) says many plants and trees have inedible seeds that are contained in hard shells and are released only when subjected to the heat of a great fire. This is probably the most attractive wrong answer choice because it also looks like it's trying to provide an explanation for the phenomenon described above. It's trying to suggest that the reason why the ancient society burned large areas of land was to extract the seeds from the hard shells. There are at least two problems with (C), however. The first problem is that the seeds are inedible. That means you can't eat them. So what are you trying to do by extracting them? One plausible explanation is that you're trying to plant them. But that's not good for this argument, because that suggests that the culture might have been agrarian. The other problem is that this explanation doesn't fit very well with the phenomenon. Even if it's true that the seeds are released only when subjected to the heat of a great fire, it's not clear that the way to extract a seed is to burn down an entire tract of land. Why not collect all the shells and just burn them? Wouldn’t that be easier than setting a whole forest on fire? Notice (D) doesn't suffer from this problem. The hypothesis fits the facts. If you're trying to move entire populations of animals, then burning large areas of land makes sense. The solution is at the right scale for the problem.

Answer Choice (E) says few early societies were aware that burning organic material can help create nutrients for soil. This suggests the preclusion of a potential explanation. Before reading (E), one potential explanation for why the ancient society burned large areas of land was to fertilize the soil. After reading (E), it seems less likely that that's what our ancient society was attempting to do. What is the significance of this? I suppose it's less likely now that our ancient society was agrarian. But this was already established in the argument.

There is evidence that a certain ancient society burned large areas of land. Some suggest that this indicates the beginning of large-scale agriculture in that society—that the land was burned to clear ground for planting. But there is little evidence of cultivation after the fires. Therefore, it is likely that this society was still a hunter-gatherer society.

Summarize Argument: Phenomenon-Hypothesis

The author concludes that the society was a hunter-gatherer society. She bases this on evidence that they burned large areas of land with little sign of farming afterward, making it unlikely they were agricultural, as some suggest.

Notable Assumptions

The author assumes that because large areas of land were burned with little evidence of farming afterward, the society must have been hunter-gatherer. She doesn’t consider why a hunter-gatherer society would burn a large area of land, or whether an agricultural society might burn large areas of land for some reason other than farming.

A

Many ancient cultures had agriculture before they began using fire to clear large tracts of land.

Irrelevant—the society in the stimulus did use fire to clear large areas of land. Whether some ancient agricultural societies did not do this doesn't matter. Instead, we need an answer that helps us determine if these fires indicate a hunter-gatherer society.

B

Hunter-gatherer societies used fire for cooking and for heat during cold weather.

Irrelevant— using fire for cooking and heat during the cold is not the same as burning large areas of land. We need to know why burning large areas of land might be evidence of a hunter-gatherer society. Whether this society used fire in other ways doesn’t matter.

C

Many plants and trees have inedible seeds that are contained in hard shells and are released only when subjected to the heat of a great fire.

Even if we assume that these inedible seeds grow into edible plants and that the best way to release them is to burn a large area of land, (C) weakens the argument because it presents evidence of an agricultural society, not a hunter-gatherer society.

D

Hunter-gatherer societies are known to have used fire to move animal populations from one area to another.

This strengthens the argument by addressing the assumption that a hunter-gatherer society would have reason to burn a large area of land at all. If hunter-gatherer societies used fire to move animals from one area to another, the author’s conclusion becomes much more plausible.

E

Few early societies were aware that burning organic material can help create nutrients for soil.

Irrelevant—even if this society didn’t know that burning organic material can enrich soil, (E) only tells us that they probably didn’t plant on the land, which was already stated in the stimulus.

This is a Strengthen question.

The argument begins with a phenomenon that a certain ancient society burned large areas of land. Naturally, we wonder why they did this. The author presents other people's hypothesis: they burned large areas of land to prepare the ground for planting, which means that the ancient society was beginning the transition to agriculture.

To test this hypothesis, we can check its predictions. One prediction would be evidence of agriculture. If it's true that they burned the ground in preparation for planting, then we should expect to find evidence of agriculture. But we have little evidence of cultivation after the fires. This strongly implies that the other people's hypothesis of transition to agriculture is wrong. And so the author concludes it is likely that the society was still a hunter-gatherer society.

Now, one quick assumption you might've noticed is whether ancient societies fall into the binary buckets of either agricultural or hunter-gatherer. That is something to keep in mind, but as it turns out, those two buckets do largely capture all societies. The answer choices don't try to undercut that assumption.

But don't forget that we still have this phenomenon presented in the beginning argument. The author hasn't given an explanation of why the ancient society burned large areas of land. She has only, rather effectively, disposed of a bad explanation.

This is where Correct Answer Choice (D) improves the reasoning of the argument. It says hunter-gatherer societies are known to have used fire to move animal populations from one area to another. This presents a plausible explanation of the phenomenon unexplained in the original argument. If this is true, then that phenomenon itself becomes support for the author's conclusion that the society was still a hunter-gatherer society.

Answer Choice (A) says many ancient cultures had agriculture before they began using fire to clear large tracts of land. This means that fire clearing of land is not necessary for the transition to agriculture. That's good to know if you were curious about early human civilization. But this has nothing to do with the argument. The fact is the particular ancient society we’re talking about did clear large areas of land with fire. We’re trying to figure out what that means about the status of their civilizational development.

Answer Choice (B) says hunter-gatherer societies use fire for cooking and for heat during cold weather. This doesn't affect the argument at all. The argument told us that this particular society used fire to burn large areas of land and then we try to argue that this particular society was still a hunter-gatherer society. Information about hunter-gatherer societies using fire to do other things doesn't help the claim.

Answer Choice (C) says many plants and trees have inedible seeds that are contained in hard shells and are released only when subjected to the heat of a great fire. This is probably the most attractive wrong answer choice because it also looks like it's trying to provide an explanation for the phenomenon described above. It's trying to suggest that the reason why the ancient society burned large areas of land was to extract the seeds from the hard shells. There are at least two problems with (C), however. The first problem is that the seeds are inedible. That means you can't eat them. So what are you trying to do by extracting them? One plausible explanation is that you're trying to plant them. But that's not good for this argument, because that suggests that the culture might have been agrarian. The other problem is that this explanation doesn't fit very well with the phenomenon. Even if it's true that the seeds are released only when subjected to the heat of a great fire, it's not clear that the way to extract a seed is to burn down an entire tract of land. Why not collect all the shells and just burn them? Wouldn’t that be easier than setting a whole forest on fire? Notice (D) doesn't suffer from this problem. The hypothesis fits the facts. If you're trying to move entire populations of animals, then burning large areas of land makes sense. The solution is at the right scale for the problem.

Answer Choice (E) says few early societies were aware that burning organic material can help create nutrients for soil. This suggests the preclusion of a potential explanation. Before reading (E), one potential explanation for why the ancient society burned large areas of land was to fertilize the soil. After reading (E), it seems less likely that that's what our ancient society was attempting to do. What is the significance of this? I suppose it's less likely now that our ancient society was agrarian. But this was already established in the argument.

This is a Most Strongly Supported question.

The stimulus says that in the past, infants who were not breast-fed were fed cow's milk. Then doctors began advising that cow's milk fed to infants should be boiled, as the boiling would sterilize the milk and prevent gastrointestinal infections potentially fatal to infants. And once this advice was widely implemented, there was an alarming increase among infants in the incidence of scurvy, which is caused by vitamin C deficiency. Breast-fed infants, however, did not contract scurvy.

While this is not an ideal experiment, it's what's known as a natural experiment. There are two groups, the "intervention" and "control" groups. The intervention group (boiling cow's milk) exhibited more incidences of scurvy than the control group (breast-fed milk). We suspect that the explanation is that boiling cow's milk was the cause. But how? Why would boiling cow's milk cause the infants to contract scurvy? The stimulus contains another fact: scurvy is caused by vitamin C deficiency. That's a clue about the causal mechanism. Together, the facts (the phenomena) strongly support the hypothesis that boiling cow's milk destroyed vitamin C, which in turn caused scurvy.

Correct Answer Choice (A) says boiled cow's milk makes less vitamin C available to the infant than does the same amount of mother's milk. This is a version of the hypothesis above. That's why it's the right answer. (A) is by no means a “must be true,” but the standard of proof is lower for MSS. You never really reach 100% validity in scientific reasoning anyway. That only happens in formal reasoning.

And notice how similar this is to Resolve Reconcile Explain. (A) would still be correct if this was an RRE question since it would explain the phenomenon in the stimulus. This reveals that the question stem is more or less superficial, and that there is an underlying unity to Logical Reasoning. And here the logic is scientific reasoning. You are presented with a natural experiment that resembles the ideal experiment and asked to come up with a reasonable hypothesis.

What's a natural experiment and why do I put quotations around "control group"? Because natural experiments are less reliable than ideal experiments. That doesn't mean they're not reliable at all. Far from it. Natural experiments can sometimes provide very strong evidence. But they are not ideal because the "control group" didn't control for everything.

Imagine you had an alternative hypothesis, say, the citrus shortage hypothesis. Under that hypothesis, there was a shortage in citrus fruits that just happened to coincide with the intervention (boiling cow's milk). Perhaps it's actually the citrus shortage that caused the increase in scurvy.

Okay, but we can preclude this hypothesis with an ideal experiment. We can run a control group. Hold everything else equal (including access to citrus) and feed the control group breast milk. If they don't develop scurvy, then it can't be the citrus shortage that caused the scurvy. That's kind of like what happened in the natural experiment of the stimulus. The difference is that we have no assurances that the breast-fed babies' exposure to citrus was the same as the intervention babies' exposure. It's possible that breast-fed infants somehow had priority access to oranges. It's just very unlikely. That distance is there, though, in the natural experiment, whereas in the ideal experiment, we have assurances that the control group did in fact control for everything. That's why natural experiments are weaker than ideal ones. How much weaker? That depends in turn on which hypotheses you're trying to eliminate. For the citrus shortage hypothesis, it's highly unlikely that the breast-fed group would have had priority access and, therefore, the natural experiment is not that much weaker than the ideal experiment.

Answer Choice (B) says infants who consume cow's milk that has not been boiled frequently contract potentially fatal gastrointestinal infections. (B) could have been correct if it had said sometimes, potentially, or even in danger of contracting. Doctors recommended the intervention precisely to prevent gastrointestinal infections, so it is a reasonable assumption that they thought of unboiled cow’s milk as an actual risk. But “frequently” is too strong to be supported.

Answer Choice (C) says mother's milk can cause gastrointestinal infections in infants. This is just a mishmash. We do know that unboiled cow's milk potentially can cause gastrointestinal infections, but can mother's milk cause it? Nothing in the stimulus suggests the answer is one way or another.

Answer Choice (D) is really attractive. If you picked (D), you probably read some alternate version of (D) that resembles the following: when doctors advised that cow's milk fed to infants be boiled, they did not know that this intervention would lead to vitamin C deficiency, which then would lead to scurvy.

Then (D) would be pretty well supported. It seems clear that when doctors began advising to boil the milk, they did not anticipate that scurvy would be a consequence. I am guessing they also did not know that infants depended on milk for their vitamin C, because if they had some other source, for example, like orange juice, who cares about the vitamin C in the milk? Just drink your orange juice.

But that is not what (D) says. (D) just says that when doctors advised cow's milk to be boiled, the cause of scurvy was a mystery. This I am not so sure about. It is totally possible that doctors knew the cause of scurvy. Lots of sailors knew vitamin C deficiency was the cause of scurvy for hundreds of years. They just did not think this intervention (boiling cow's milk) would result in vitamin C deficiency and hence scurvy.

Answer Choice (E) says that when doctors advised that cow's milk fed to infants be boiled, most mothers did not breast-feed their infants. We know that when this intervention happened, there were some infants who were drinking cow's milk and some who were breast-fed. But nothing in the stimulus says which set is larger, so (E) is totally unsupported.

A

Boiled cow’s milk makes less vitamin C available to infants than does the same amount of mother’s milk.

B

Infants who consume cow’s milk that has not been boiled frequently contract potentially fatal gastrointestinal infections.

C

Mother’s milk can cause gastrointestinal infections in infants.

D

When doctors advised that cow’s milk fed to infants should be boiled, they did not know that scurvy was caused by vitamin C deficiency.

E

When doctors advised that cow’s milk fed to infants should be boiled, most mothers did not breast-feed their infants.

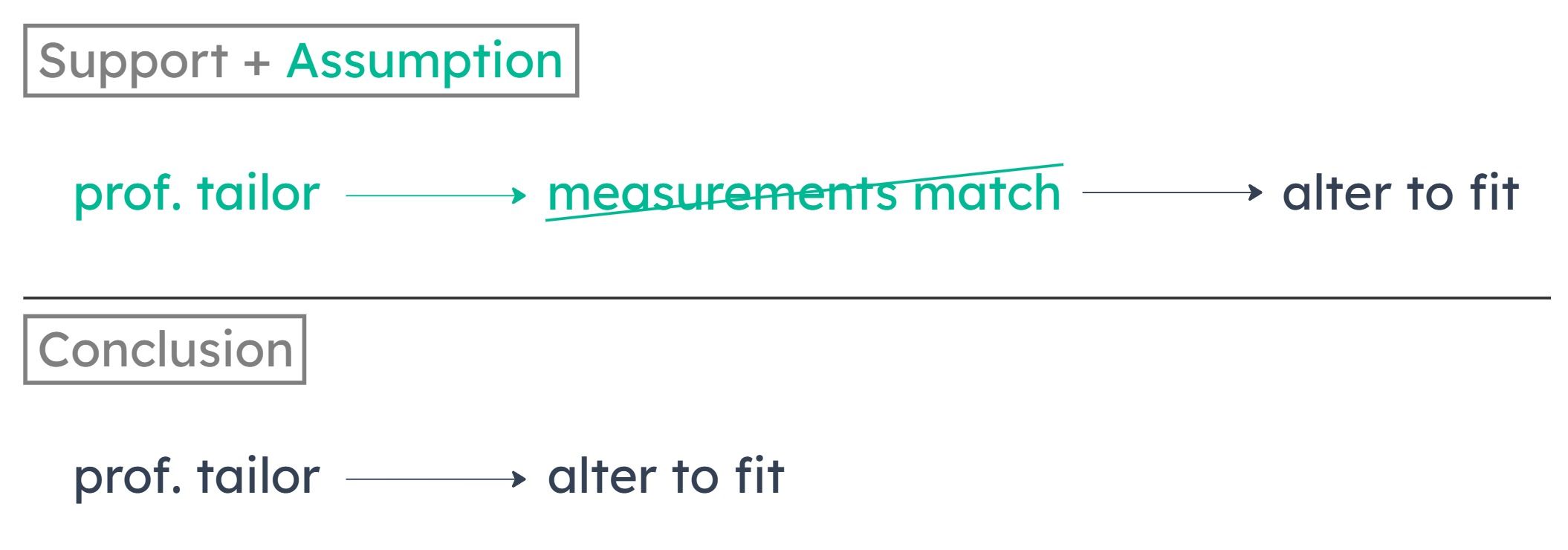

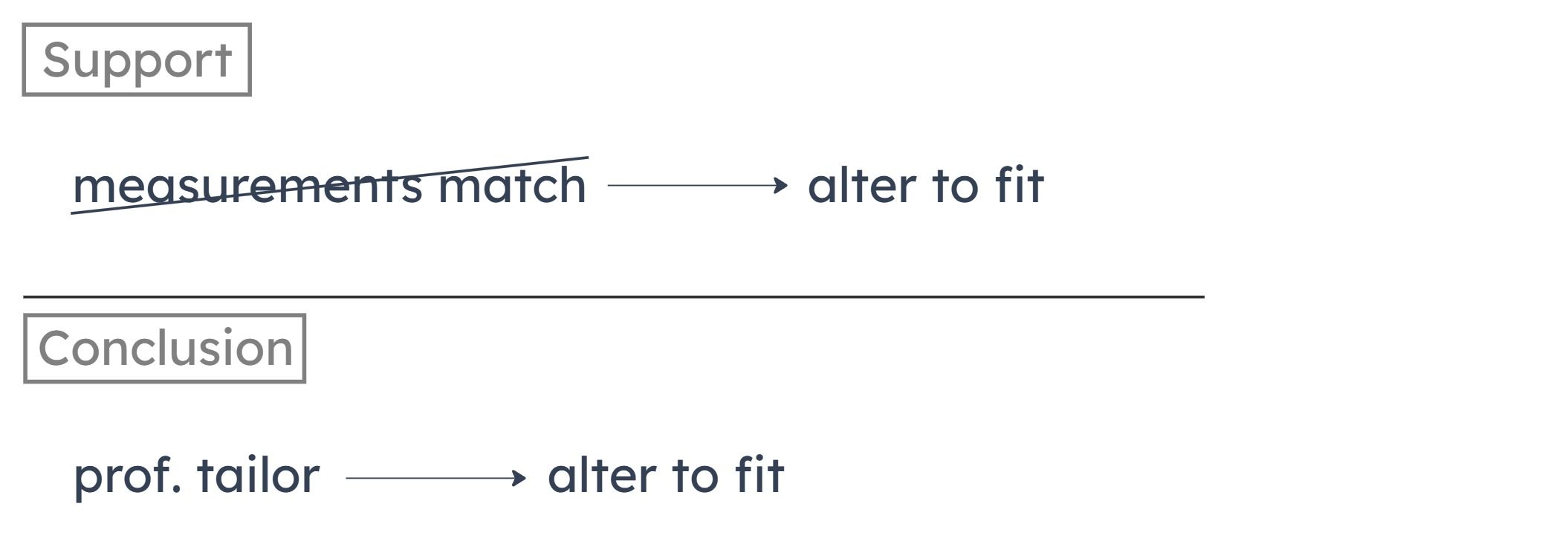

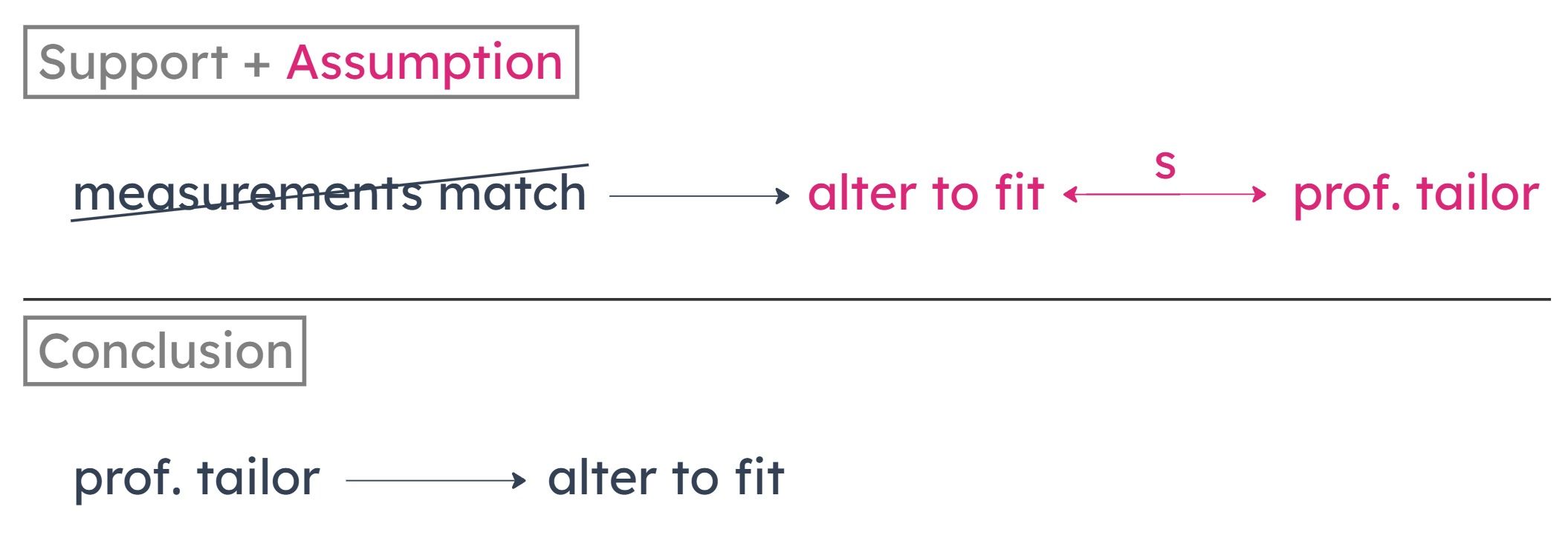

Note that the first sentence provides no support for the conclusion.

Also, the conclusion is that professional tailors always alter the pattern, no exceptions. But the premise allows for an exception: tailors in general alter the pattern unless the wearer’s measurements already match the pattern.

The premise would lead to the conclusion if we knew that for professional tailors specifically, the exception never applies. That is, for a professional tailor, the wearer’s measurements never match the pattern.

A

Most manufactured patterns do not already accommodate the future distortion of fabrics that shrink or stretch.

B

At least some tailors who adjust patterns to the wearer and to the fabrics used are professional tailors.

C

The best tailors are those most able to alter patterns to fit the wearer exactly.

D

All professional tailors sew only for people whose measurements do not exactly match their chosen patterns.