We’ve got a MSS question which we can tell from the question stem: If the statements above are true, which one of the following is the most strongly supported on the basis of them?

The stimulus starts with what looks like a sentence of contextual information which introduces us to a category: common threats to life. The embedded phrase between the commas gives us examples of common threats to life: automobile and industrial accidents. We’re told that only unusual instances of common threats like these receive coverage from the news media.

We then have a shift into what looks like our potential argument (remember that MSS requires us to find a conclusion that completes said argument). This shift is indicated by the “however” that’s wedged into the middle of the next sentence. We then get a premise that introduces us to another category: rare threats. We also get an example of rare threats: product tampering. We are told that instances of rare threats are seen as news and universally reported by reporters in featured stories.

Ok so we know that the media always reports instances of rare threats, but only reports unusual instances of common threats. We then get some information about how the media impacts the population at large: people tend to estimate the risk of threats based on how often those threats come to their attention.

What’s a common way things come to our attention? Well, the media, right? Do we see a potential connection here?

Media covers rare threats instead of common threats. People see coverage of rare threats but not common threats. People perceive greater risk from rare threats because they estimate risk based on how often something comes to their attention.

Seems like a good synthesis of the information we’ve been given! Now let’s go to the answer choices:

Answer Choice (A) We have no information about governmental action. We know about news coverage of risks and the way that individuals perceive risk, but we do not have enough information to draw any conclusions about the government.

Answer Choice (B) We are only given information about the amount of coverage that two types of risk are given. We don’t know anything about the quality of risk and how that affects people. We just know that the amount that people think about risks impacts how those individuals estimate the likelihood of those potential risks coming to fruition.

Correct Answer Choice (C) We know that people estimate risk based on how often it comes to their attention. People who get information primarily from the news media (the same news media that covers rare threats more than common threats) would be likely to perceive higher risk of uncommon (i.e. rare) threats relative to common threats because of the amount of coverage they receive. This is is fully supported by our stimulus, and therefore, correct!

Answer Choice (D) We don’t get any information in our stimulus about how the element of time plays into threats or coverage of threats, so there is nothing to support this answer.

Answer Choice (E) Hard to know where to start with this one! We don't have any information about money or resources spent on threats, so we can safely (and quickly) rule this AC out.

News media are more likely to report on rare or unusual threats to life than on common threats.

People who estimate risk based on news reports likely underestimate the risk of common threats and overestimate the risk of rare or unusual threats.

A

Whether governmental action will be taken to lessen a common risk depends primarily on the prominence given to the risk by the news media.

B

People tend to magnify the risk of a threat if the threat seems particularly dreadful or if those who would be affected have no control over it.

C

Those who get their information primarily from the news media tend to overestimate the risk of uncommon threats relative to the risk of common threats.

D

Reporters tend not to seek out information about long-range future threats but to concentrate their attention on the immediate past and future.

E

The resources that are spent on avoiding product tampering are greater than the resources that are spent on avoiding threats that stem from the weather.

A

It takes for granted that the economic incentive to construct colonies on the Moon will grow sufficiently to cause such a costly project to be undertaken.

B

It takes for granted that the only way of relieving severe overcrowding on Earth is the construction of colonies on the Moon.

C

It overlooks the possibility that colonies will be built on the Moon regardless of any economic incentive to construct such colonies to house some of the population.

D

It overlooks the possibility that colonies on the Moon might themselves quickly become overcrowded.

E

It takes for granted that none of the human population would prefer to live on the Moon unless Earth were seriously overcrowded.

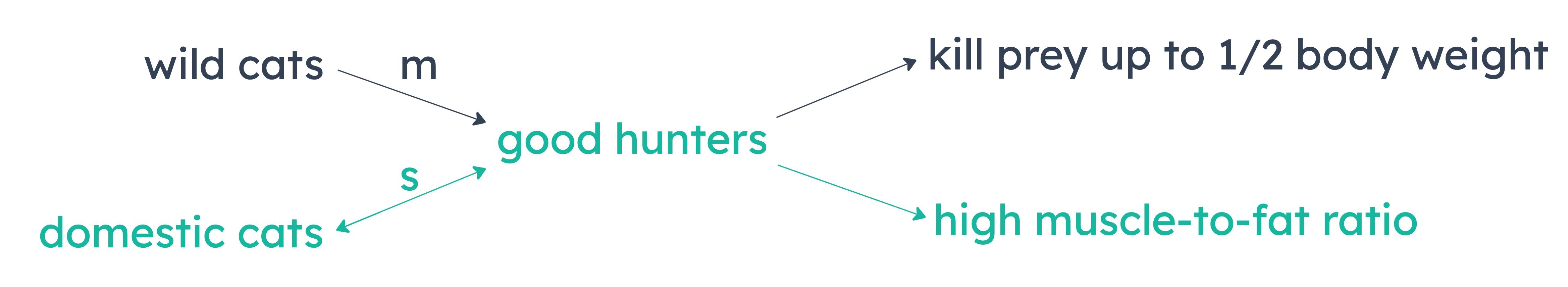

Most wildcats can kill prey that weigh up to half of their body weight.

Some cats that can kill prey that weigh up to half of their body weight have a high muscle-to-fat ratio.

Some domestic cats can kill prey that weigh up to half of their body weight.

Some domestic cats have a high muscle-to-fat ratio.

A

Some cats that have a high muscle-to-fat ratio are not good hunters.

B

A smaller number of domestic cats than wild cats have a high muscle-to-fat ratio.

C

All cats that are bad hunters have a low muscle-to-fat ratio.

D

Some cats that have a high muscle-to-fat ratio are domestic.