Because most children under 6 are egocentric and selfish in their attitudes toward animals.

In addition, most children under 6 don’t understand that animals are independent creatures with their own feelings and needs.

To go further, we can anticipate a more specific connection between the premises and the conclusion. Any answer that connects a feature we know about most children under 6 to “should not have pets” can be correct:

If one is egocentric and selfish in attitudes toward animals, then one shouldn’t have a pet.

or

If one doesn’t understand that animals are independent creatures with their own feelings and needs, then one shouldn’t have a pet.

A

Most children who are egocentric and selfish in their attitudes towards animals rely on others to take care of a pet.

B

Children who are old enough to understand that animals are independent creatures with their own feelings and needs should be allowed to have pets.

C

Most children who are egocentric and selfish in their attitudes towards animals do not have pets.

D

Most children are egocentric and selfish in their attitudes towards their pets and do not understand that their pets are independent creatures with their own feelings and needs.

E

The only children who should have pets are those who understand that their pets are independent creatures with their own feelings and needs.

This is a PSA question.

The difficulty in this question is partially in the complexity of the argument. Where is the main conclusion? There’s also a sub-conclusion present! It’s also partially in the answers. Some of the principles on offer tempt us to react based on what we know to be true or false in the world. But if we cut through these difficulties, this is a straightforward PSA question with a straightforward PSA answer: P→C.

First, the ranger says it’s unfair to cite people for fishing in the newly restricted areas. Okay, why? Because the people are probably unaware of the changes in the rules. Okay, why do you say that? Because many of “us rangers” are even unaware of the changes in the rules. So here’s the complex argument.

Minor premise: Many rangers are unaware of the new rules.

Major premise/sub-conclusion: Park visitors are probably unaware of the new rules.

Main conclusion: Unfair to cite visitors for violations.

But there’s one more pesky sentence at the end that says until after we really try to publicize these new rules, the most we should do is to issue a simple warning. How does this fit in? Maybe this is the main-main conclusion? Perhaps. It’s unfair to give citations, therefore issue a warning instead. That makes sense. Maybe this is the second half of the main conclusion? Park visitors aren’t aware of the new rules, therefore don’t cite them (negative), just give a warning (positive). That makes sense too. The conclusion is an injunction with a positive and negative component. Either way you interpret the last statement will be just fine. Something ambiguous like this won’t form the basis of the right/wrong answers. So, for simplicity, I’ll just interpret this to be part of the main conclusion.

Minor premise: Many rangers are unaware of the new rules.

Major premise/sub-conclusion: Park visitors are probably unaware of the new rules.

Main conclusion: Unfair to cite visitors; instead, give warnings.

Before we look at the answers, note that there are two places for us to PSA the support. We can bridge the minor premise to the sub-conclusion or we can bridge the major premise to the main conclusion. What would those bridges, in our own words, look like?

Minor descriptive-P → descriptive-C bridge: If some rangers are unaware of the new rules, then probably visitors are unaware.

Major descriptive-P → prescriptive-C bridge: If visitors are unaware of the new rules, then they should only be given a warning.

Correct Answer Choice (A) supplies the major descriptive-P → prescriptive-C bridge. It says that people should not be cited for violating laws of which they are unaware. If unaware, then should not be cited. Granted, it doesn’t “justify” the “simple warning” bit of the conclusion but this is a PSA question, after all, and not an SA question. The bar isn’t set so high as to require validity.

If you eliminated (A), ask yourself why. I don’t know, but might it be because (A) runs against what you know to be true in the world? Our legal system has a principle that ignorance of the law is no excuse. Yet (A) contradicts this principle. Is that why you were repelled by (A)?

Answer Choice (C) pretends to supply the minor P→C bridge. It says that the public should not be expected to know more about the law than any law enforcement officer. That lowers the bar for what the public “should be expected to know” all the way down to the knowledge possessed by the least-informed officer. So if any officer is unaware of the new regulations, then the public should not be expected to be aware either. On the face of it, this is appealing. The minor premise says some rangers aren’t aware, and with this principle, we can conclude that the public should not be expected to be aware. But wait a second, the sub-conclusion isn't prescriptive. It isn’t about what the public should or should not be expected to know. It’s a factual, probabilistic, descriptive statement about what the public does or does not know. To justify the minor support structure, we needed a descriptive-P → descriptive-C bridge.

But it’s appealing because we “like” this principle. We think it’s right. We think it’s just. But ask yourself, even if this principle is true, where does it get us? It gets us to the position that the public shouldn’t be expected to know about the new regulations. Okay. Then what? Does that mean they also therefore should be cited? That depends on whether ignorance of the law is an excuse. So you’re back to (A) anyway.

Answer Choice (B) says regulations should be widely publicized. Okay, so publicize them. But what should we do in the meantime? Should we cite or merely warn violators? (B) is embarrassingly silent.

Answer Choice (D) puts the burden on the public. It says that people who fish in a public park should make every effort to be fully aware of the rules. Where does this principle get us? That if there’s some lapse in knowledge about the rules, then it’s squarely on the shoulders of the public? That doesn’t help justify the conclusion.

Answer Choice (E) is a principle that affords violators the right to explain themselves, a right to a defense. Okay, calm down. Nobody is talking about a trial here. We’re just trying to figure out if a warning is enough or if a citation is warranted. It doesn’t matter what the violator has to say about how they view the regulations and whether they think it applies to them.

This is a PSA question.

The difficulty in this question is partially in the complexity of the argument. Where is the main conclusion? There’s also a sub-conclusion present! It’s also partially in the answers. Some of the principles on offer tempt us to react based on what we know to be true or false in the world. But if we cut through these difficulties, this is a straightforward PSA question with a straightforward PSA answer: P→C.

First, the ranger says it’s unfair to cite people for fishing in the newly restricted areas. Okay, why? Because the people are probably unaware of the changes in the rules. Okay, why do you say that? Because many of “us rangers” are even unaware of the changes in the rules. So here’s the complex argument.

Minor premise: Many rangers are unaware of the new rules.

Major premise/sub-conclusion: Park visitors are probably unaware of the new rules.

Main conclusion: Unfair to cite visitors for violations.

But there’s one more pesky sentence at the end that says until after we really try to publicize these new rules, the most we should do is to issue a simple warning. How does this fit in? Maybe this is the main-main conclusion? Perhaps. It’s unfair to give citations, therefore issue a warning instead. That makes sense. Maybe this is the second half of the main conclusion? Park visitors aren’t aware of the new rules, therefore don’t cite them (negative), just give a warning (positive). That makes sense too. The conclusion is an injunction with a positive and negative component. Either way you interpret the last statement will be just fine. Something ambiguous like this won’t form the basis of the right/wrong answers. So, for simplicity, I’ll just interpret this to be part of the main conclusion.

Minor premise: Many rangers are unaware of the new rules.

Major premise/sub-conclusion: Park visitors are probably unaware of the new rules.

Main conclusion: Unfair to cite visitors; instead, give warnings.

Before we look at the answers, note that there are two places for us to PSA the support. We can bridge the minor premise to the sub-conclusion or we can bridge the major premise to the main conclusion. What would those bridges, in our own words, look like?

Minor descriptive-P → descriptive-C bridge: If some rangers are unaware of the new rules, then probably visitors are unaware.

Major descriptive-P → prescriptive-C bridge: If visitors are unaware of the new rules, then they should only be given a warning.

Correct Answer Choice (A) supplies the major descriptive-P → prescriptive-C bridge. It says that people should not be cited for violating laws of which they are unaware. If unaware, then should not be cited. Granted, it doesn’t “justify” the “simple warning” bit of the conclusion but this is a PSA question, after all, and not an SA question. The bar isn’t set so high as to require validity.

If you eliminated (A), ask yourself why. I don’t know, but might it be because (A) runs against what you know to be true in the world? Our legal system has a principle that ignorance of the law is no excuse. Yet (A) contradicts this principle. Is that why you were repelled by (A)?

Answer Choice (C) pretends to supply the minor P→C bridge. It says that the public should not be expected to know more about the law than any law enforcement officer. That lowers the bar for what the public “should be expected to know” all the way down to the knowledge possessed by the least-informed officer. So if any officer is unaware of the new regulations, then the public should not be expected to be aware either. On the face of it, this is appealing. The minor premise says some rangers aren’t aware, and with this principle, we can conclude that the public should not be expected to be aware. But wait a second, the sub-conclusion isn't prescriptive. It isn’t about what the public should or should not be expected to know. It’s a factual, probabilistic, descriptive statement about what the public does or does not know. To justify the minor support structure, we needed a descriptive-P → descriptive-C bridge.

But it’s appealing because we “like” this principle. We think it’s right. We think it’s just. But ask yourself, even if this principle is true, where does it get us? It gets us to the position that the public shouldn’t be expected to know about the new regulations. Okay. Then what? Does that mean they also therefore should be cited? That depends on whether ignorance of the law is an excuse. So you’re back to (A) anyway.

Answer Choice (B) says regulations should be widely publicized. Okay, so publicize them. But what should we do in the meantime? Should we cite or merely warn violators? (B) is embarrassingly silent.

Answer Choice (D) puts the burden on the public. It says that people who fish in a public park should make every effort to be fully aware of the rules. Where does this principle get us? That if there’s some lapse in knowledge about the rules, then it’s squarely on the shoulders of the public? That doesn’t help justify the conclusion.

Answer Choice (E) is a principle that affords violators the right to explain themselves, a right to a defense. Okay, calm down. Nobody is talking about a trial here. We’re just trying to figure out if a warning is enough or if a citation is warranted. It doesn’t matter what the violator has to say about how they view the regulations and whether they think it applies to them.

This is a Must Be True question.

This question tests your ability to manipulate grammar to reveal underlying logical relationships between sets. In particular, we are dealing with sets of intersections and supersets and subsets.

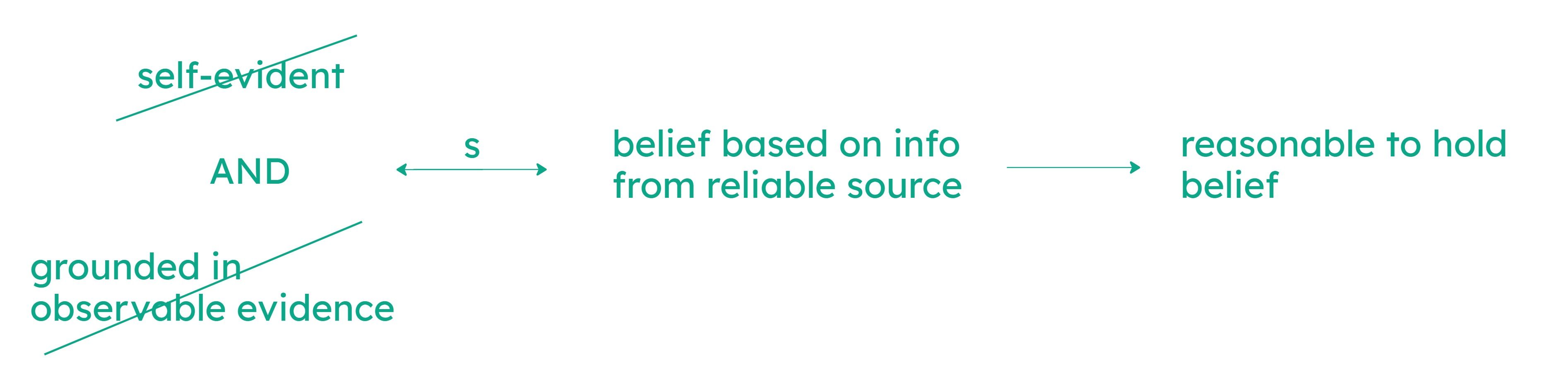

The stimulus states that if a belief is based on information from a reliable source, then it is reasonable to maintain that belief. This is a standard conditional claim using the “if... then...” formulation. Let's kick the idea of “a belief” up into the domain. This will simplify the analysis. You wouldn't know at this moment to do this. You have to finish reading the stimulus.

Kicking the idea of “a belief” as the subject up into the domain, we get to talk about the properties of beliefs. And it's those properties that have a sufficiency necessity relationship. The sufficient property is “based on reliable information.” If that's true, then the necessary property is “reasonableness.”

The next claim is an intersection claim. We know this from the presence of the word “some.” Some beliefs are based on information from a reliable source and yet are neither self-evident nor grounded in observable evidence. This is where you might notice that the subject once again is belief. The sentence here is talking about a triple intersection between three different sets of properties of beliefs.

- based on reliable information (same set as the sufficient condition in the previous sentence)

- not self-evident

- not grounded in observable evidence

These three sets have an intersection. But we also know from the first sentence that if based on reliable information, then reasonable. That implies “reasonable” gets to join this intersection with “not self-evident” and “not grounded in observable evidence” as well.

Using logic, first, represent the intersection of 2 and 3 as simply A. B will represent based on reliable information. C will represent reasonable. The triple intersection can now be represented as A ←s→ B. The conditional is B → C. The valid inference is A ←s→ C. Again, that’s just the triple intersection between “reasonable” and 2 and 3.

If that was confusing, consider this. If a cat is mild-mannered, then it’s domestic. Some mild-mannered cats are large and fluffy. Therefore, some domestic cats are large and fluffy. That’s analogous to the question here. Kick the subject “cats” up into the domain. The “some” premise describes a triple intersection between mild-mannered, large, and fluffy. Because mild-mannered implies domestic, we know that domestic also intersects with large and fluffy.

Hopefully that clears up the logic. Translating it back into English reveals that we have many options. “Some domestic cats are large and fluffy” is probably the most straightforward translation. But we could also say, “Among the large cats, some domestic ones are fluffy.” Or we could say, “Among the fluffy cats, some large ones are domestic.” The order of the modifiers in “some” intersections doesn’t matter. “Some” can be reversibly read.

So, there are many ways to translate the valid inference from the actual stimulus back into English. We could say, “Some beliefs that are neither self-evident nor grounded in observable evidence are nonetheless reasonable.” Or we could state this as Correct Answer Choice (E) does. Among reasonable beliefs that are not self-evident, there are some beliefs that are not grounded in observable evidence. Or even differently still. Grammar is the reason for this flexibility. As long as you know that you're just trying to express a triple intersection, you should be all set.

Answer Choice (A) says beliefs for which a person does not have observable evidence are unreasonable. This is a mishmash of the concepts in the stimulus. What must be true is that some beliefs for which a person does not have observable evidence are reasonable. Or alternatively, we could say that unreasonable beliefs must not be based on unreliable information.

Answer Choice (B) says beliefs based on information from a reliable source are self-evident. This is also a mishmash of the concepts above. We have no information to make claims about self-evident beliefs.

Answer Choice (C) says all reasonable beliefs for which a person has no observable evidence are based on information from a reliable source. This does not validly follow from the premises. But if we changed the quantifier “all” into the quantifier “some,” then it would follow validly.

Answer Choice (D) says if the belief is not grounded in observable evidence then it is not self-evident either. This also does not follow. The relationship between these two concepts is only one of intersection. We don't know if the two sets have a superset-subset relationship.

Some beliefs that are neither self-evident nor grounded in observable evidence are reasonable.

A

Beliefs for which a person does not have observable evidence are unreasonable.

B

Beliefs based on information from a reliable source are self-evident.

C

All reasonable beliefs for which a person has no observable evidence are based on information from a reliable source.

D

If a belief is not grounded in observable evidence, then it is not self-evident either.

E

Among reasonable beliefs that are not self-evident, there are some beliefs that are not grounded in observable evidence.

This is a Must Be True question.

This question tests your ability to manipulate grammar to reveal underlying logical relationships between sets. In particular, we are dealing with sets of intersections and supersets and subsets.

The stimulus states that if a belief is based on information from a reliable source, then it is reasonable to maintain that belief. This is a standard conditional claim using the “if... then...” formulation. Let's kick the idea of “a belief” up into the domain. This will simplify the analysis. You wouldn't know at this moment to do this. You have to finish reading the stimulus.

Kicking the idea of “a belief” as the subject up into the domain, we get to talk about the properties of beliefs. And it's those properties that have a sufficiency necessity relationship. The sufficient property is “based on reliable information.” If that's true, then the necessary property is “reasonableness.”

The next claim is an intersection claim. We know this from the presence of the word “some.” Some beliefs are based on information from a reliable source and yet are neither self-evident nor grounded in observable evidence. This is where you might notice that the subject once again is belief. The sentence here is talking about a triple intersection between three different sets of properties of beliefs.

- based on reliable information (same set as the sufficient condition in the previous sentence)

- not self-evident

- not grounded in observable evidence

These three sets have an intersection. But we also know from the first sentence that if based on reliable information, then reasonable. That implies “reasonable” gets to join this intersection with “not self-evident” and “not grounded in observable evidence” as well.

Using logic, first, represent the intersection of 2 and 3 as simply A. B will represent based on reliable information. C will represent reasonable. The triple intersection can now be represented as A ←s→ B. The conditional is B → C. The valid inference is A ←s→ C. Again, that’s just the triple intersection between “reasonable” and 2 and 3.

If that was confusing, consider this. If a cat is mild-mannered, then it’s domestic. Some mild-mannered cats are large and fluffy. Therefore, some domestic cats are large and fluffy. That’s analogous to the question here. Kick the subject “cats” up into the domain. The “some” premise describes a triple intersection between mild-mannered, large, and fluffy. Because mild-mannered implies domestic, we know that domestic also intersects with large and fluffy.

Hopefully that clears up the logic. Translating it back into English reveals that we have many options. “Some domestic cats are large and fluffy” is probably the most straightforward translation. But we could also say, “Among the large cats, some domestic ones are fluffy.” Or we could say, “Among the fluffy cats, some large ones are domestic.” The order of the modifiers in “some” intersections doesn’t matter. “Some” can be reversibly read.

So, there are many ways to translate the valid inference from the actual stimulus back into English. We could say, “Some beliefs that are neither self-evident nor grounded in observable evidence are nonetheless reasonable.” Or we could state this as Correct Answer Choice (E) does. Among reasonable beliefs that are not self-evident, there are some beliefs that are not grounded in observable evidence. Or even differently still. Grammar is the reason for this flexibility. As long as you know that you're just trying to express a triple intersection, you should be all set.

Answer Choice (A) says beliefs for which a person does not have observable evidence are unreasonable. This is a mishmash of the concepts in the stimulus. What must be true is that some beliefs for which a person does not have observable evidence are reasonable. Or alternatively, we could say that unreasonable beliefs must not be based on unreliable information.

Answer Choice (B) says beliefs based on information from a reliable source are self-evident. This is also a mishmash of the concepts above. We have no information to make claims about self-evident beliefs.

Answer Choice (C) says all reasonable beliefs for which a person has no observable evidence are based on information from a reliable source. This does not validly follow from the premises. But if we changed the quantifier “all” into the quantifier “some,” then it would follow validly.

Answer Choice (D) says if the belief is not grounded in observable evidence then it is not self-evident either. This also does not follow. The relationship between these two concepts is only one of intersection. We don't know if the two sets have a superset-subset relationship.

This is an RRE question.

The stimulus tells us that, in general, significant intellectual advances occur in societies with a stable political system. It then goes on to tell us that in ancient Athens during a period of great political and social unrest, Plato and Aristotle made significant intellectual progress.

As with all RRE questions, whether we feel like the phenomenon is surprising or the phenomenon contains some apparent internal inconsistency depends on how much we know about the subject matter. That's just another way of saying it depends on what assumptions we bring into the phenomenon. In this question, whether we think Plato and Aristotle represent a counterexample to the general rule depends on our assumptions about the underlying causal mechanism. The general rule that great intellectual progress occurs in societies with politically stable systems doesn't reveal causation. It merely invites us to speculate that perhaps it's the stability of the political system which causally contributes to the intellectual progress. This is what makes Athens in the time of Plato and Aristotle look like a counterexample. This is not a terrible hypothesis. But it's not the only hypothesis.

Correct Answer Choice (C) suggests a different hypothesis, a different causal mechanism. It tells us that financial support for intellectual endeavors is typically unavailable in unstable political environments, but in ancient Athens wealthy citizens provided such support. This answer suggests an explanation for both the general rule and the apparent counterexample, thus reconciling them. Why is it that we tend to see great intellectual progress take place in politically stable systems? It's not that political stability directly causes intellectual advancement. Rather, political stability enables financial support for intellectual progress and, conversely, lack of political stability typically destroys that financial support. But it’s the financial support that’s causally important. This means that even in a politically unstable society, like Athens in the time of Plato and Aristotle, as long as there is financial support, then intellectual progress can occur anyway. This answer is not ideal. It does require the assumption that financial support for intellectual endeavors has a causal impact on intellectual progress.

Answer Choice (A) says the political systems that have emerged since the time of Plato and Aristotle have in various ways been different from the political system in ancient Athens. This seems so obvious that it's not worth the pixels on which it's displayed. Ancient Athens had a particular political system in the time of Plato and Aristotle. Of course other kinds of political systems have emerged since then. This is a banal fact that doesn't explain the phenomenon above.

Answer Choice (B) says the citizens of ancient Athens generally held in high esteem people who were accomplished intellectually. This is a recurring type of wrong answer. It’s ignoring half the phenomenon in order to explain the other half. We’ll see this again in (D). While (B) may suggest an explanation of the intellectual progress made in Athens, that intellectual progress nonetheless feels like a counterexample to the general rule. If we were simply asked to come up with a list of the causes of intellectual progress in Athens, this answer might be one item on the list. That is to say, one motivating factor for Plato or Aristotle to make progress was prestige or esteem. But that wasn't the task. Our job was to reconcile the apparent counterexample with the general rule. This answer doesn't do that. Now that I know Plato was motivated by esteem, the fact that he made progress in a time of political instability still seems to buck the general rule.

Answer Choice (D) says significant intellectual advances sometimes, though not always, lead to stable political environments. This answer is similar to (B) in that it's explaining only half the phenomenon while ignoring the other half. (D) can function as an explanation of the general rule. Why do we tend to see significant intellectual advances occur in societies with stable political systems? It's because significant intellectual advances cause that stability. Fair enough. But that leaves unexplained why in ancient Athens the unparalleled intellectual progress made there didn't also result in political stability.

Answer Choice (E) says many thinkers besides Plato and Aristotle contributed to the intellectual achievements of ancient Athens. This is a cookie-cutter wrong answer choice. It doesn't explain the phenomenon above. It merely adds to the phenomenon in need of an explanation. The stimulus already gave us a problem. We needed to explain why Plato and Aristotle seemed to have bucked the trend. (E) merely tells us that it's not just Plato and Aristotle that seem to have bucked the trend; there were other thinkers as well.

A

The political systems that have emerged since the time of Plato and Aristotle have in various ways been different from the political system in ancient Athens.

B

The citizens of ancient Athens generally held in high esteem people who were accomplished intellectually.

C

Financial support for intellectual endeavors is typically unavailable in unstable political environments, but in ancient Athens such support was provided by wealthy citizens.

D

Significant intellectual advances sometimes, though not always, lead to stable political environments.

E

Many thinkers besides Plato and Aristotle contributed to the intellectual achievements of ancient Athens.

This is a Weakening question.

The journalist says when judges do not maintain strict control over their courtrooms, lawyers often try to influence jury verdicts by using inflammatory language and by badgering witnesses. And these obstructive behaviors hinder the jury's efforts to reach a correct verdict. Therefore, whenever lawyers engage in such behavior, it is reasonable to doubt whether the verdict is correct.

Does the conclusion follow? We know obstructive behaviors hinder the jury's effort to reach a correct verdict. But hinder isn't the same thing as prevent. That assumes the hindrance is effective. It's possible that the hindrance prevents the jury from reaching a correct verdict but it's also possible that the hindrance is simply an annoyance, something that the jury can shrug off. The point is that to hinder is just that, to hinder. It's not as dispositive as the argument wants us to believe.

Answer Choice (A) says court proceedings overseen by judges who are strict in controlling lawyers' behaviors are known to result sometimes in incorrect verdicts. I am already not interested in (A) because the argument is contemplating a specific situation where judges do not maintain control over their courtrooms. (A) does not engage with this premise and tells us that in a different world where judges do control their courtrooms, juries also reach wrong verdicts.

To make (A) better, we can edit the conclusion to say that only when lawyers engage in such behavior is it reasonable to doubt the veracity of the verdict. This version of the conclusion is saying that when we have a reason to doubt a verdict, it must be because of obstructive behavior. And (A) would weaken by illustrating a counterexample: juries mess up even when lawyers do not engage in obstructive behavior.

You will see a very similar cookie-cutter wrong Answer Choice (B) in Question 24 of this section, which also tells you to forget the situation at hand and talks about a different world. Just as you find patterns that repeat in the stimulus and correct answers, you will find recurring patterns in the wrong answer choices as well.

Answer Choice (B) says lawyers tend to be less concerned than are judges about whether the outcomes of jury trials are just or not. This is a comparative claim and somewhat obvious. We have an adversarial system where lawyers are concerned about winning and judges are concerned about justice. At best, (B) explains why lawyers have to be kept in check because they are not so concerned about justice.

Answer Choice (C) says people who are influenced by inflammatory language are very unlikely to admit they were influenced by such language. Let’s give (C) a charitable reading and say that the people influenced by inflammatory language here are the jurors. But even with this reading, (C) does not weaken the argument. If jurors were influenced, it does not matter if they are humble or reflective enough to admit that they were. If anything, (C) just tells us that this hindrance might actually lead to reasonable doubt about the verdict.

Answer Choice (E) says the selection of jurors is based in part on an assessment of the likelihood that they are free from bias. This is true in reality. For example, in a corporation versus an individual case, you would want jurors who are not already biased against corporations. However, the argument is not about bias. (E) would have been better if it said the selection of jurors is based in part on an assessment of the likelihood that they are free from being influenced by inflammatory language.

But even then, (E) would not be a great answer choice because it is denying the premise that obstructive behaviors do hinder the jury's effort to some extent. And while you do sometimes see explicit contradictions to a premise in the LSAT, this is generally not how the test writers weaken arguments.

Correct Answer Choice (D) says obstructive courtroom behavior by a lawyer is seldom effective in cases where jurors are also presented with legitimate evidence. This is the only answer choice that addresses the gap between the premise and the conclusion.

Remember we said that just because obstructive behaviors hinder the jury's efforts, we cannot assume that this hindrance is effective. And (D) confirms this. It says there's this other factor, legitimate evidence, that renders obstructive behaviors ineffective.

You might object and say (D) requires an assumption that cases where jurors are presented with legitimate evidence are most cases, or at minimum, the cases where lawyers engage in obstructive behaviors. But this is not an unreasonable assumption. We have a functioning judicial system with robust rules of evidence, and in the vast majority of cases, there is legitimate evidence. You might think it is unfair to be expected to know this, but what you are expected to know is how to identify the assumption that (D) requires and compare it to assumptions required by the other answer choices. While (D) may not be the perfect answer choice, it still is the best answer choice.

The Journalist also assumes that the impact of obstructive behaviors outweighs that of other evidence/testimony