A

the argument does not evaluate all aspects of the typological theory

B

the argument confuses a necessary condition for species distinction with a sufficient condition for species distinction

C

the argument, in its attempt to refute one theory of species classification, presupposes the truth of an opposing theory

D

the argument takes a single fact that is incompatible with a theory as enough to show that theory to be false

E

the argument does not explain why sibling species cannot interbreed

A

Individuals do not have control over their actions when they feel certain emotions.

B

If a person is morally blameworthy for something, then that person is responsible for it.

C

Although a person may sometimes be unjustifiably angry, jealous, or resentful, there are occasions when these emotions are appropriate.

D

If an emotion is under a person’s control, then that person cannot hold others responsible for it.

E

The emotions for which a person is most commonly blamed are those that are under that person’s control.

In a poll of a representative sample of a province’s residents, the provincial capital was the city most often selected as the best place to live in that province. Since the capital is also the largest of that province’s many cities, the poll shows that most residents of that province generally prefer life in large cities to life in small cities.

Summarize Argument

The author concludes that most residents in the province prefer large cities to small cities. As support, he notes that the capital is the largest city in the province and was most often selected as the best place to live in a poll of the province’s residents.

Identify and Describe Flaw

(1) The author assumes that people chose the capital as the best city because it’s large. But if they chose it for other reasons, like its job opportunities or food scene, he can’t assume that these residents prefer large cities.

(2) The author confuses plurality and majority. He assumes that the option with more votes than any other (plurality) is also the option with the majority of the votes (>50%). But maybe 40% of people chose the capital, while 30% chose City A and 30% chose City B. If so, it’s not true that most residents prefer the capital.

A

overlooks the possibility that what is true of the residents of the province may not be true of other people

Like (B), the author’s conclusion is only about the preferences of the residents of the province. It doesn’t matter if other people share these preferences.

B

does not indicate whether most residents of other provinces also prefer life in large cities to life in small cities

Like (A), the author’s conclusion is only about the preferences of the residents of this province. The preferences of the residents of other provinces are irrelevant.

C

takes for granted that when people are polled for their preferences among cities, they tend to vote for the city that they think is the best place to live

The author may assume this, but it doesn’t explain why his argument is vulnerable to criticism. The poll is seeking to measure what city the residents think is the best place to live.

D

overlooks the possibility that the people who preferred small cities over the provincial capital did so not because of their general feelings about the sizes of cities, but because of their general feelings about capital cities

The author overlooks the possibility that people who preferred the capital city didn’t do so because of their general feelings about the sizes of cities, but because of their general feelings about capital cities.

E

overlooks the possibility that most people may have voted for small cities even though a large city received more votes than any other single city

The author confuses plurality and majority. Just because the capital city received more votes than any other city doesn’t mean that most residents chose the capital. Maybe most people voted for small cities, even though the capital had more votes than any of the small cities.

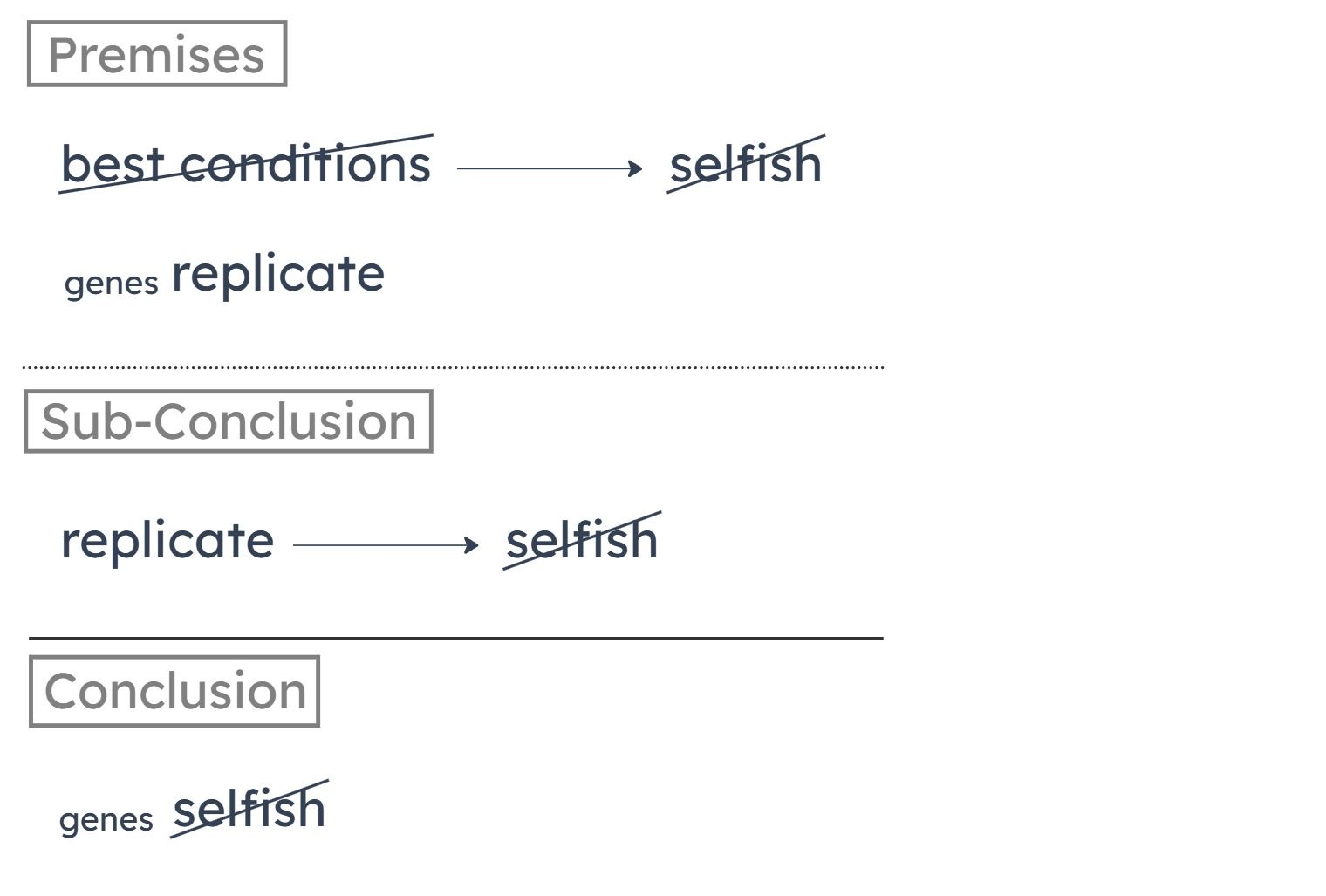

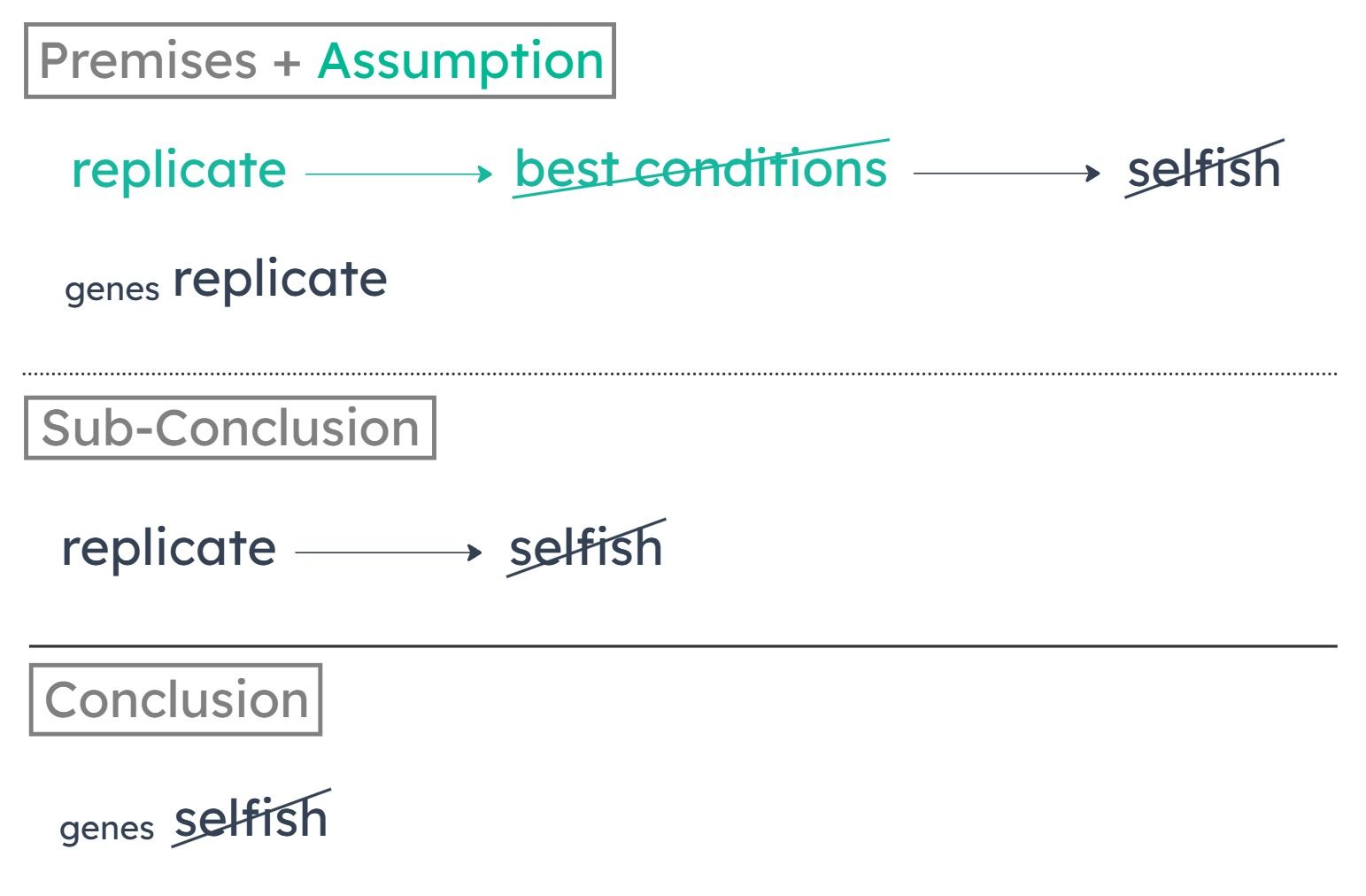

A

Bringing about the best conditions for oneself is less important than doing this for others.

B

Creating replicas of oneself does not help bring about the best conditions for oneself.

C

The behavioral definition of “selfish” is incompatible with its everyday definition.

D

To ignore the fact that self-replication is not limited to genes is to misunderstand genetic behavior.

E

Biologists have insufficient evidence about genetic behavior to determine whether it is best described as selfish.

Additionally, we are speaking specifically about genes and replication, not genetic behavior overall.

Designer: Any garden and adjoining living room that are separated from one another by sliding glass doors can visually merge into a single space. If the sliding doors are open, as may happen in summer, this effect will be created if it does not already exist and intensified if it does. The effect remains quite strong during colder months if the garden is well coordinated with the room and contributes strong visual interest of its own.

Summary

A Designer says that any garden and adjoining living room separated by a sliding glass door can visually merge into a single space. If the doors are left open, this effect will be created if it is not already present. If they are already visually merged, the effect will be intensified. If the garden is well coordinated with the room and contributes a strong visual interest, the effect will remain quite strong during colder months.

Strongly Supported Conclusions

If the sliding doors are closed, this effect can/cannot be present.

If the doors are left open, this effect will be present.

A

A garden separated from an adjoining living room by closed sliding glass doors cannot be well coordinated with the room unless the garden contributes strong visual interest.

The stimulus does not give this condition. The stimulus only says that being well coordinated and contributing a strong visual interest is sufficient for the effect to remain strong in the winter.

B

In cold weather, a garden and an adjoining living room separated from one another by sliding glass doors will not visually merge into a single space unless the garden is well coordinated with the room.

This is too strong to support. The stimulus says that the effect will remain *strong* if the room is well coordinated and contributes a strong visual interest. The stimulus gives no condition that can conclude that the room does not visually merge.

C

A garden and an adjoining living room separated by sliding glass doors cannot visually merge in summer unless the doors are open.

This is antisupported. The doors being open in the summer *enhances* the effect if it is already present and provides the effect if it is not.

D

A garden can visually merge with an adjoining living room into a single space even if the garden does not contribute strong visual interest of its own.

This reflects the reasoning in the stimulus. The room contributing a strong visual interest is only linked to the effect remaining quite strong during *colder* months. The room can still visually merge without this condition.

E

Except in summer, opening the sliding glass doors that separate a garden from an adjoining living room does not intensify the effect of the garden and room visually merging into a single space.

This is antisupported. The stimulus only uses summer as an example, not a definitive rule. The stimulus says that the effect will be enhanced or created if the doors are left open and does not specify any time of year.

Last summer, after a number of people got sick from eating locally caught anchovies, the coastal city of San Martin advised against eating such anchovies. The anchovies were apparently tainted with domoic acid, a harmful neurotoxin. However, a dramatic drop in the population of P. australis plankton to numbers more normal for local coastal waters indicates that it is once again safe to eat locally caught anchovies.

"Surprising" Phenomenon

Why does the decrease in plankton numbers make the anchovies safe to eat?

Objective

The correct answer will establish a relationship between the number of P. australis and the safety of the anchovies. It will imply that fewer plankton means less domoic acid in the anchovies or that a decrease in plankton makes the domoic acid in anchovies safer to consume.

A

P. australis is one of several varieties of plankton common to the region that, when ingested by anchovies, cause the latter to secrete small amounts of domoic acid.

This states that anchovies will secrete, not contain, domoic acid after ingesting P. australis. It is not implied that anchovies secreting domoic acid must contain that acid, nor that domoic acid in the water builds up in anchovies’ bodies.

B

P. australis naturally produces domoic acid, though anchovies consume enough to become toxic only when the population of P. australis is extraordinarily large.

This explains why a decrease in P. australis numbers makes the anchovies safe. Once the plankton are less prevalent, the domoic acid in anchovies lowers to safe levels.

C

Scientists have used P. australis plankton to obtain domoic acid in the laboratory.

This does not imply that high P. australis numbers cause anchovies to contain domoic acid. It is possible that P. australis does not naturally produce or contain domoic acid, in which case its relationship to the anchovies remains unexplained.

D

A sharp decline in the population of P. australis is typically mirrored by a corresponding drop in the local anchovy population.

This does not explain why locally caught anchovies are safe to eat. It does not imply that the surviving anchovies are in any way safer to consume.

E

P. australis cannot survive in large numbers in seawater that does not contain significant quantities of domoic acid along with numerous other compounds.

This establishes a condition necessary for the survival of P. australis, but does not imply that a decrease in plankton must accompany a decrease in domoic acid. It is possible the plankton died for a different reason and domoic acid is still prevalent in the water.

Brigita: That traditional definition of full employment was developed before the rise of temporary and part-time work and the fall in benefit levels. When people are juggling several part-time jobs with no benefits, or working in a series of temporary assignments, as is now the case, 5 percent unemployment is not full employment.

A

what definition of full employment is applicable under contemporary economic conditions

B

whether it is a good idea, all things considered, to allow the unemployment level to drop below 5 percent

C

whether a person with a part-time job should count as fully employed

D

whether the number of part-time and temporary workers has increased since the traditional definition of full employment was developed

E

whether unemployment levels above 5 percent can cause inflation levels to rise