Inventor: All highly successful entrepreneurs have as their main desire the wish to leave a mark on the world. Highly successful entrepreneurs are unique in that whenever they see a solution to a problem, they implement that idea. All other people see solutions to problems but are too interested in leisure time or job security to always have the motivation to implement their ideas.

Summary

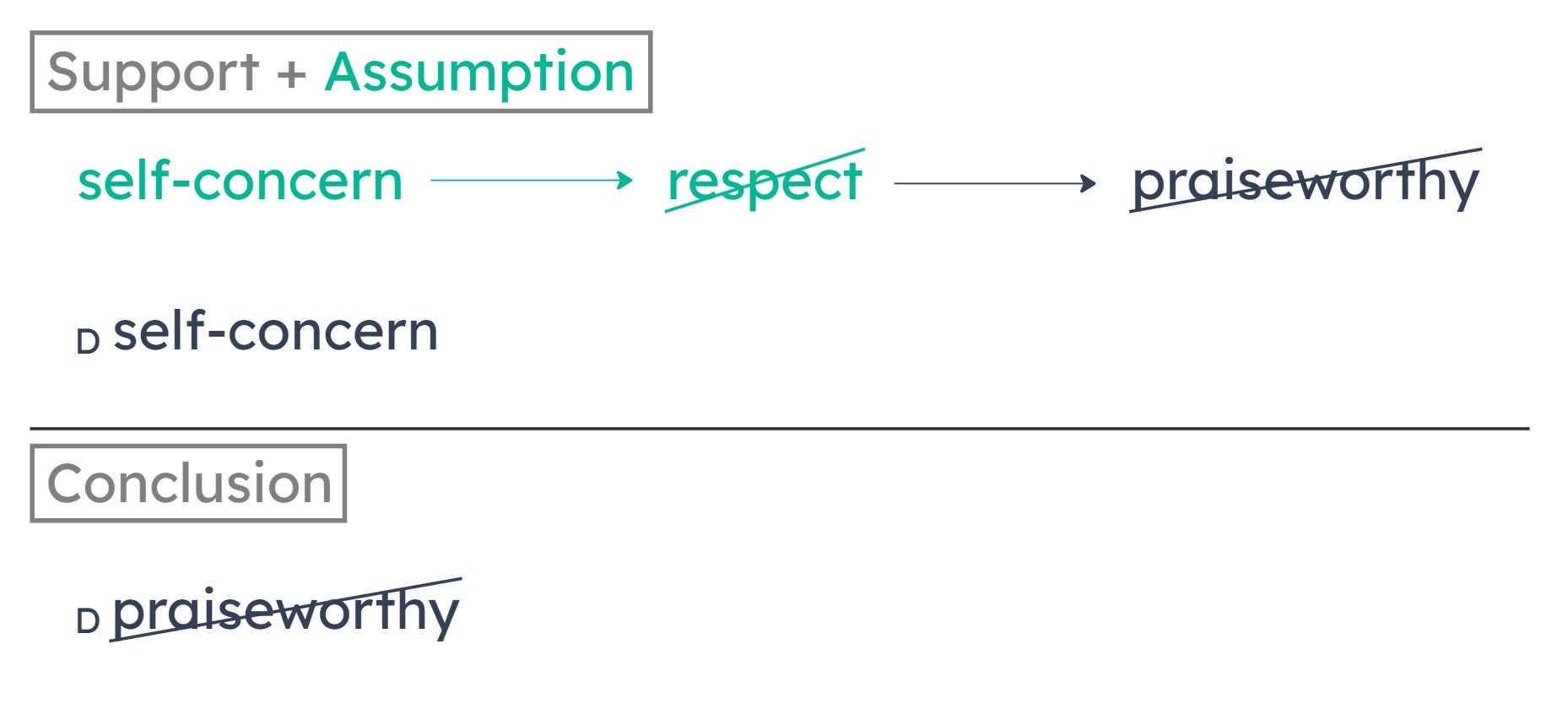

The stimulus can be diagrammed as follows:

Notable Valid Inferences

People who implement the solutions that they see whenever they detect them have as their main desire the wish to leave a mark on the world.

A

Most people do not want to leave a mark on the world because trying to do so would reduce their leisure time or job security.

Could be false. The stimulus does not discuss quantities, so we cannot infer what “most people” don’t want.

B

All people who invariably implement their solutions to problems have at least some interest in leisure time or job security.

Could be false. We don’t know anything about how interested in leisure time or job security the invariable problem solvers are.

C

The main desire of all people who implement solutions whenever they detect them is to leave a mark on the world.

Must be true. As shown below, implementing solutions whenever one detects them is a sufficient condition for having one’s main desire be to leave a mark on the world.

D

Generally, highly successful entrepreneurs’ interests in leisure time or job security are not strong enough to have a negative impact on their ability to see solutions to problems.

Could be false. From the stimulus, we just know that when highly successful entrepreneurs see solutions, they implement the solutions. We don’t know anything about how often they see solutions, or what factors influence their ability to see solutions.

E

All people whose main desire is to implement their solutions to problems leave a mark on the world.

Could be false. The stimulus discusses people who implement their solutions, not people whose main desire is to implement their solutions. Similarly, the stimulus discusses those whose main desire is to leave a mark on the world, not those who actually leave a mark.

That Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale (1610–1611) is modeled after Euripides’ Alcestis (fifth century B.C.) seems undeniable. However, it is generally accepted that Shakespeare knew little or no Greek, so Euripides’ original play would be an unlikely source. Thus, it seems most likely that Shakespeare came to know Euripides’ play through a Latin translation.

Summarize Argument: Phenomenon-Hypothesis

The author hypothesizes that Shakespeare probably learned about Euripedes’ play through a Latin translation. This is based on the fact that Shakespeare knew little or no Greek, which suggests he didn’t read the original version of Euripedes’ play.

Notable Assumptions

The author assumes that Shakespeare didn’t learn about the play through a translation in another language, such as English. The author also assumes that Shakespeare learned about Euripedes’ play through a translation, as opposed to learning about the play through a conversation or through other kinds of communiation with people who knew about the play. The author also assumes that Shakespeare could read Latin.

A

Latin phrases that were widely used in England during Shakespeare’s time appear in a number of his plays.

This doesn’t suggest that Shakespeare knew Latin. If the phrases were widely used, that suggests he may have simply used phrases that came to be part of general parlance. (Think about a phrase like “schadenfreude” - you may know what this means without knowing German.)

B

The only English language version of Alcestis available in Shakespeare’s time differed drastically from the original in ways The Winter’s Tale does not.

This provides evidence against the theory that Shakespeare learned about Euripedes’ play through an English translation.

C

Paul Buchanan’s 1539 Latin translation of Alcestis was faithful to the original and widely available during the 1600s.

This strengthens by affirming that there was in fact a Latin translation of Euripedes’ play in existence at the time Shakespeare wrote The Winter’s Tale.

D

Shakespeare’s father’s community standing makes it probable that Shakespeare attended grammar school, where Latin would have been a mandatory subject.

This strengthens by providing evidence that Shakespeare knew Latin.

E

There is strong evidence to suggest that Shakespeare relied on Latin translations of Greek plays as sources for some of his other works.

This strengthens by showing that there is precedent for the idea that Shakespeare was influenced by Latin translations of Greek plays.

A

He proposed two alternative hypotheses, each of which would explain a set of observations.

B

His investigation partially confirmed prior observations but led to a radical reinterpretation of those observations.

C

He proposed a theory and then proceeded to confirm it through observation.

D

He used different methods from those used in earlier studies but arrived at the same conclusion.

E

His investigation replicated previous studies but yielded a more limited set of observational data.

A

For a piece of music to be classified as jazz, it must feature some amount of improvisation.

B

The later music featuring improvisation was heavily influenced by early jazz.

C

Some of the later music featuring improvisation was performed by artists who had been jazz musicians earlier in their careers.

D

Many types of music other than jazz feature a great deal of improvisation.

E

The later music featuring improvisation has much more in common with early jazz than with any other type of music.

The author concludes that Costa’s reasoning can be discounted. This is based on the fact that Costa’s own theories assign works of art to period styles.

A

The argument confuses a necessary condition for discounting a person’s reasoning with a sufficient condition for discounting a person’s reasoning.

B

The argument overlooks the possibility that theoreticians can hold radically different theories at different times.

C

The argument rejects the reasoning on which a criticism is based merely on the grounds that that very criticism could be applied to theories of the person who offered it.

D

The argument presumes, without providing justification, that what is true of art in general must also be true of every particular type of art.

E

The argument presumes, without providing justification, that theories about one type of art cannot be compared to theories about another.

Downing was motivated by concern for his own well-being.

In order for it to be morally praiseworthy to be honest, it is necessary that the honesty be done out of respect for morality.

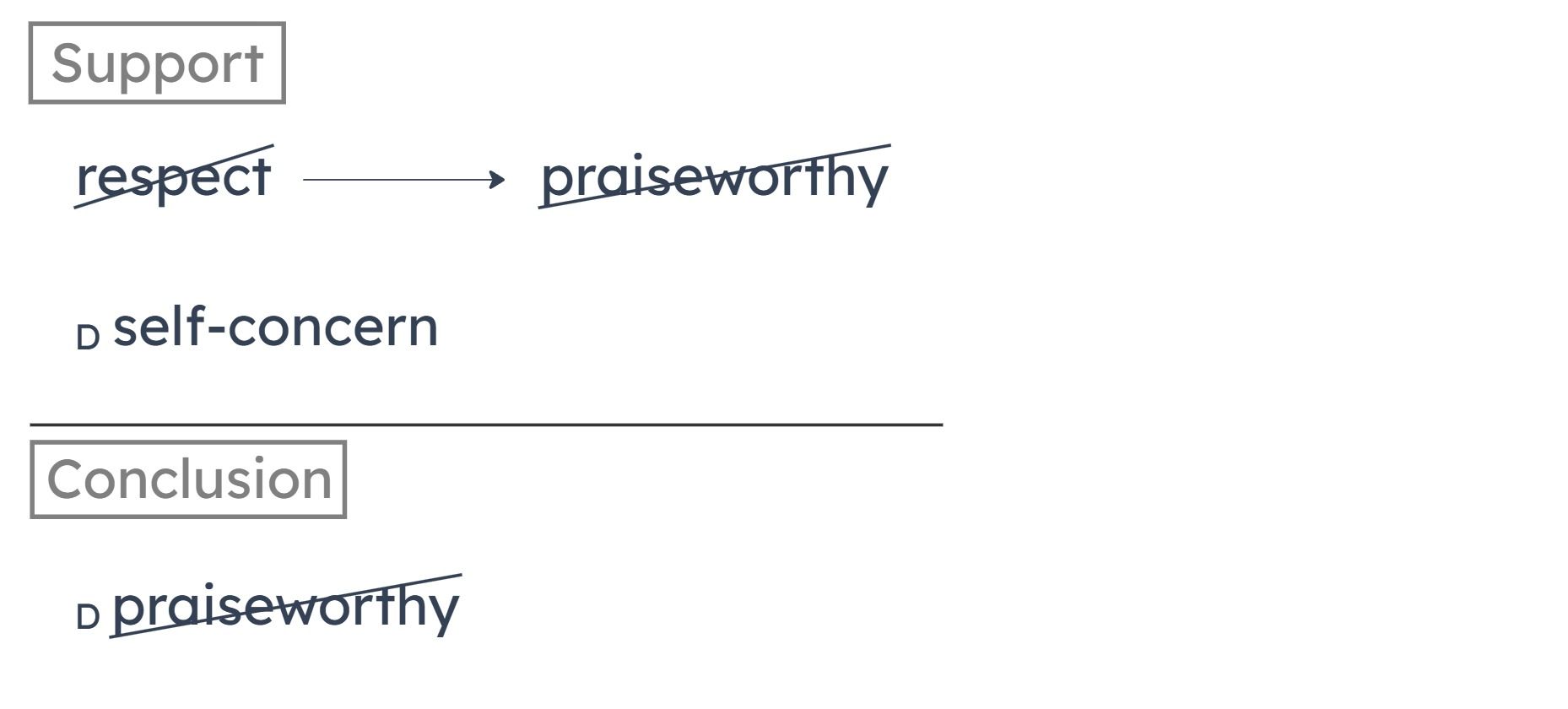

Another premise tells us that Downing was motivated by self-concern. Does this guarantee that he was not motivated by respect for morality? Not necessarily, since someone can have multiple motivations. To make this argument valid, then, we want to establish that if someone’s motivation is self-concern, then they cannot also be motivated by morality.

A

An action motivated by concern for oneself cannot be deserving of moral condemnation.

B

Some actions that are essentially honest are not morally praiseworthy.

C

An action performed out of respect for morality cannot also be an action motivated by concern for oneself.