Columnist: Research shows significant reductions in the number of people smoking, and especially in the number of first-time smokers in those countries that have imposed stringent restrictions on tobacco advertising. This provides substantial grounds for disputing tobacco companies’ claims that advertising has no significant causal impact on the tendency to smoke.

Summarize Argument

The columnist concludes that, contrary to what tobacco companies claim, advertising indeed has an effect on smoking habits. As evidence, she cites research showing that countries with the strictest tobacco advertising laws also have the greatest reduction in the number of people who smoke.

Notable Assumptions

Based on a correlation between tobacco advertising laws and smoking rates, the author assumes that the former causes the latter. This means the author doesn’t believe the relationship is the inverse (i.e. decreasing rates of smoking cause stringent tobacco advertising laws), or that some third factor (i.e. health campaigns, social attitudes) aren’t responsible for both strict tobacco advertising laws and declining smoking rates.

A

People who smoke are unlikely to quit merely because they are no longer exposed to tobacco advertising.

While the author indeed claims that countries with stringent advertising laws see a decline in smoking, she specifies that decline is most prominent among first-time smokers. Even if current smokers didn’t quit due to the laws, would-be smokers were deterred.

B

Broadcast media tend to have stricter restrictions on tobacco advertising than do print media.

We don’t care which sort of media is strictest. We’re trying to weaken the causal relationship between advertising laws and smoking rates.

C

Restrictions on tobacco advertising are imposed only in countries where a negative attitude toward tobacco use is already widespread and increasing.

This adds a third factor that isn’t smoking rates or advertising laws. Negative attitudes towards tobacco use cause a decline in smoking and strict tobacco laws.

D

Most people who begin smoking during adolescence continue to smoke throughout their lives.

Like (A), this tells us many people don’t quit. That’s fine—the laws still have an effect on first-time smokers, as well as perhaps some long-time ones.

E

People who are largely unaffected by tobacco advertising tend to be unaffected by other kinds of advertising as well.

We have no idea what percentage of people are unaffected by tobacco advertising. This could weaken if most people were unaffected by tobacco advertising, but we don’t have that information.

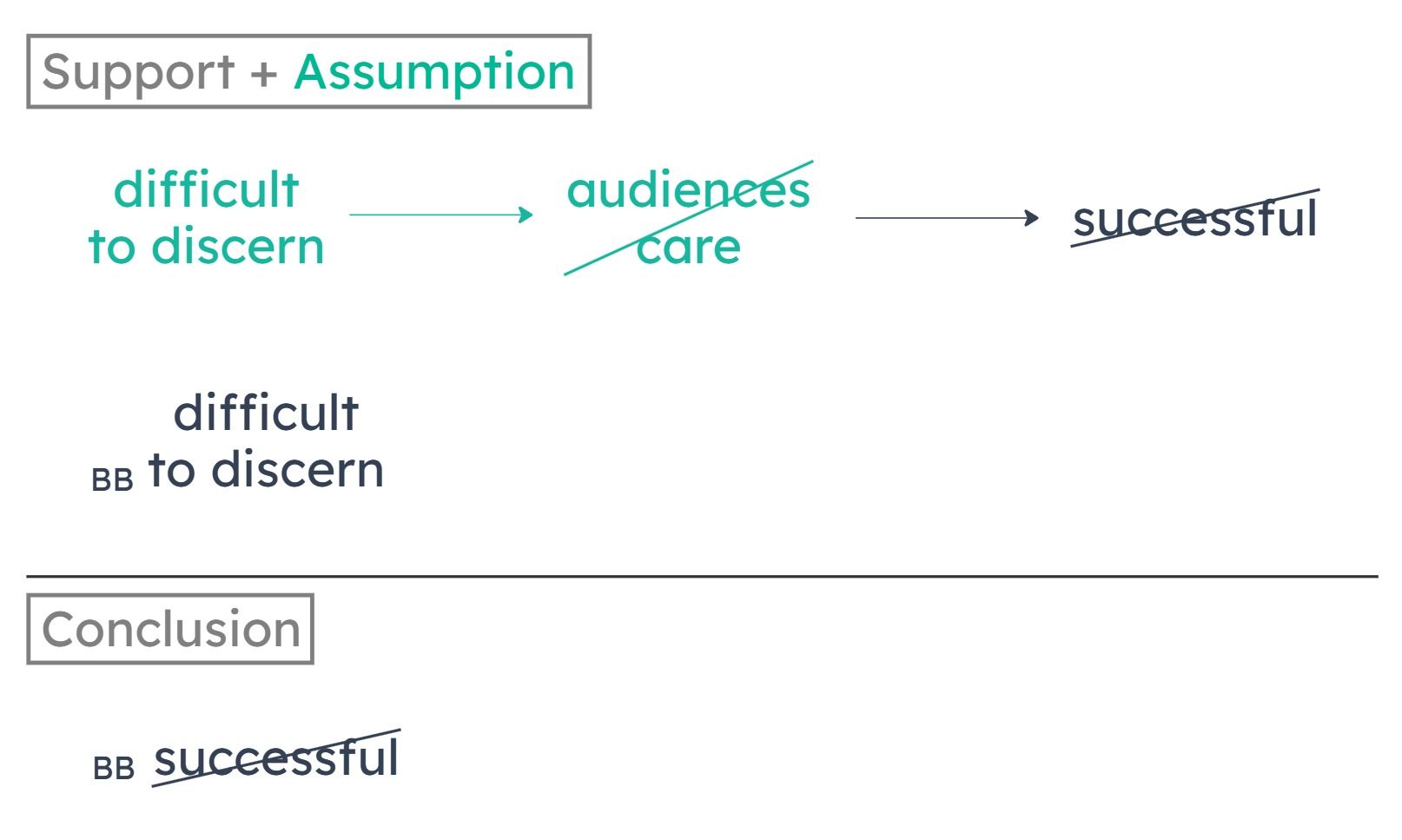

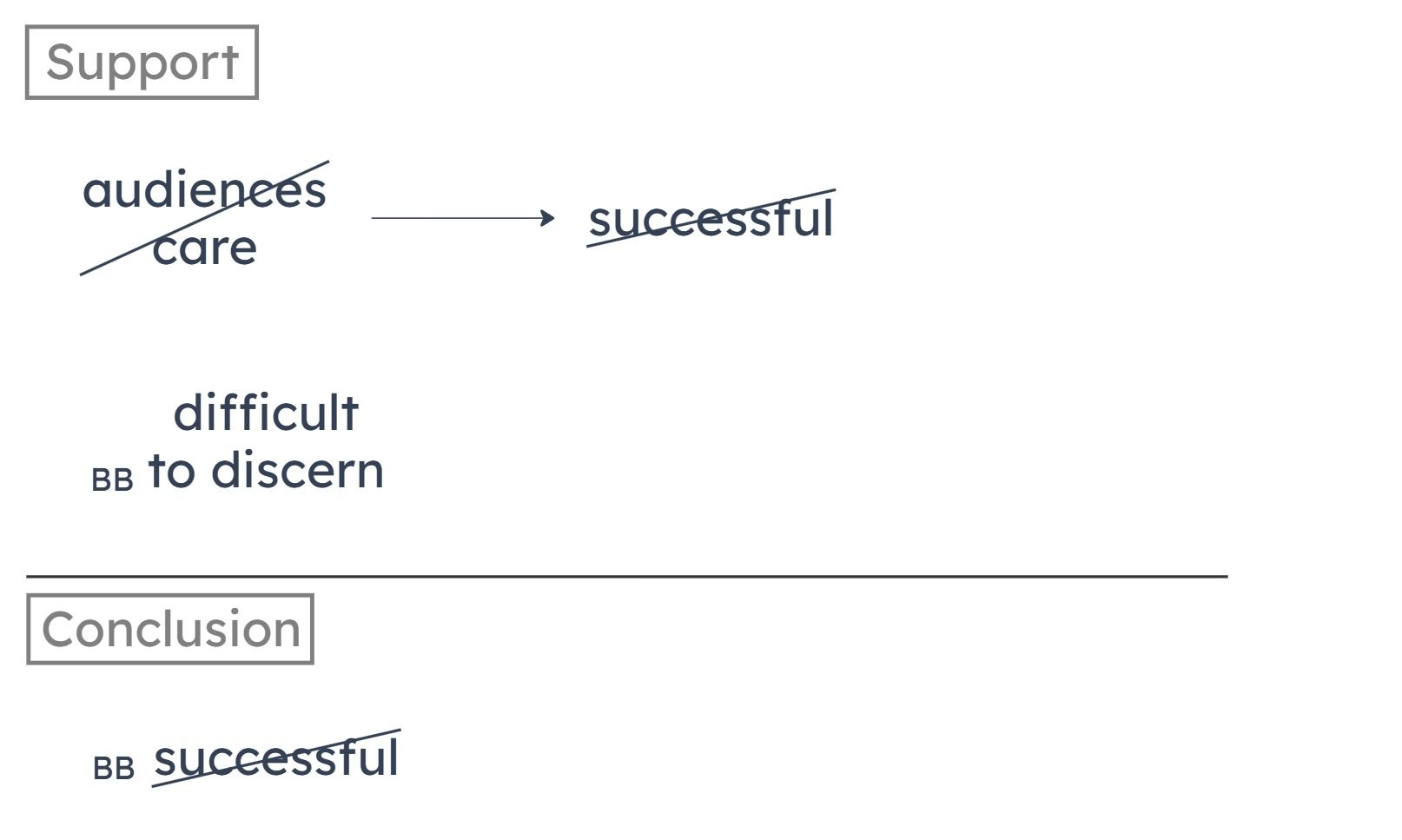

In Brecht’s plays, the audiences and actors find it difficult to discern any of the characters’ personalities.

In order to be a successful drama, audiences must care what happens to at least some of the characters.

The other premise tells us that audiences/actors find it difficult to discern characters’ personalities in Brecht’s plays. If we can show that this difficulty in discerning characters’ personalities implies that audiences won’t care about the characters, that would provide the missing link.

A

An audience that cannot readily discern a character’s personality will not take any interest in that character.