A

using a claim about what most people appreciate to support an aesthetic principle

B

appealing to an aesthetic principle to defend the tastes that people have

C

explaining a historical fact in terms of the artistic preferences of people

D

appealing to a historical fact to support a claim about people’s artistic preferences

E

considering historical context to defend the artistic preferences of people

A

Implementing flexible schedules would be an effective means of increasing the job satisfaction and efficiency of managers who do not already have scheduling autonomy.

B

Flexible-schedule policies should be expected to improve the morale of some individual employees but not the overall morale of a company’s workforce.

C

Flexible schedules should be expected to substantially improve a company’s productivity and employee satisfaction in the long run.

D

There is little correlation between managers’ job satisfaction and their ability to set their own work schedules.

E

The typical benefits of flexible-schedule policies cannot be reliably inferred from observations of the effects of such policies on managers.

A

Most people who voted in the election that Lopez won did not watch the debate.

B

Most people in the live audience watching the debate who were surveyed immediately afterward said that they thought that Tanner was more persuasive in the debate than was Lopez.

C

The people who watched the televised debate were more likely to vote for Tanner than were the people who did not watch the debate.

D

Most of the viewers surveyed immediately prior to the debate said that they would probably vote for Tanner.

E

Lopez won the election over Tanner by a very narrow margin.

Editor: Most of the books of fiction we have published were submitted by literary agents for writers they represented; the rest were received directly from fiction writers from whom we requested submissions. No nonfiction manuscript has been given serious attention, let alone been published, unless it was from a renowned figure or we had requested the manuscript after careful review of the writer’s book proposal.

Summary

If a fiction book was published → submitted by a literary agent OR received directly by request.

If a nonfiction book has been given serious attention (or published) → from a renowned figure OR requested after review of book proposal.

Very Strongly Supported Conclusions

There’s no obvious conclusion to draw from the stimulus. Just keep in mind that we have one rule for what must be true if a fiction book was published, and we have another rule for what must be true if a nonfiction book was given serious attention or published.

A

Most unrequested manuscripts that the publishing house receives are not given serious attention.

Not supported, because most unrequested manuscripts might be from a renowned figure. Or, they might also be fiction manuscripts submitted by literary agents. This is why most unrequested manuscripts still might be given serious attention.

B

Most of the books that the publishing house publishes that are not by renowned authors are books of fiction.

We don’t know the proportion of books that are fiction among non-renowned authors. It’s possible that every book by a non-renowned author is a nonfiction one (that was published after review of the book proposal).

C

If a manuscript has received careful attention at the publishing house, then it is either a work of fiction or the work of a renowned figure.

Not supported, because a manuscript that gets careful attention could be a nonfiction one that was requested after careful review of the book proposal.

D

The publishing house is less likely to give careful consideration to a manuscript that was submitted directly by a writer than one that was submitted by a writer’s literary agent.

We don’t know anything about the comparative likelihood of giving careful consideration. Notice that the rule about fiction books doesn’t say anything about careful consideration.

E

Any unrequested manuscripts not submitted by literary agents that the publishing house has published were written by renowned figures.

Supported. If a manuscript is unrequested, and not submitted by a literary agent, then it can’t be a book of fiction. So, it must be a nonfiction book. And if it’s a nonfiction book that’s published, if it’s not requested, then it must be from a renowned figure.

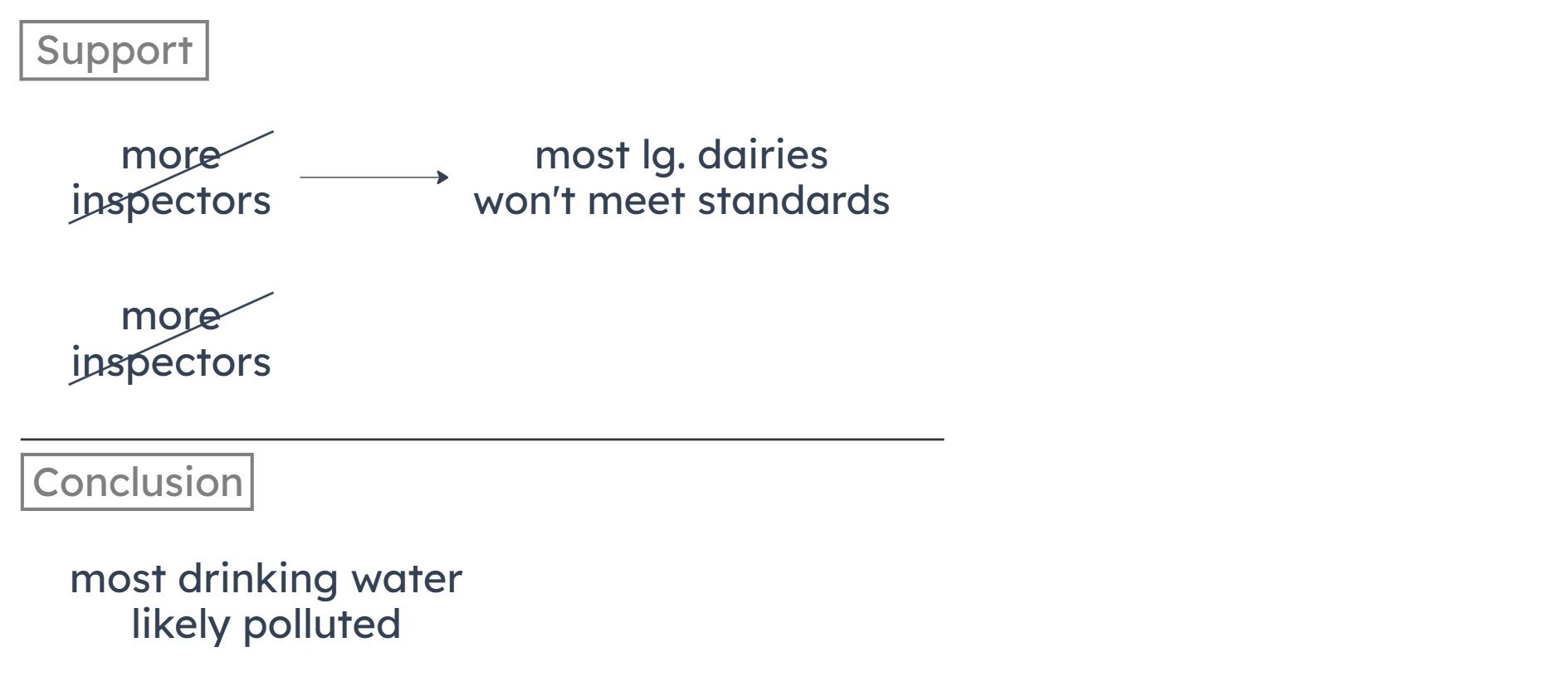

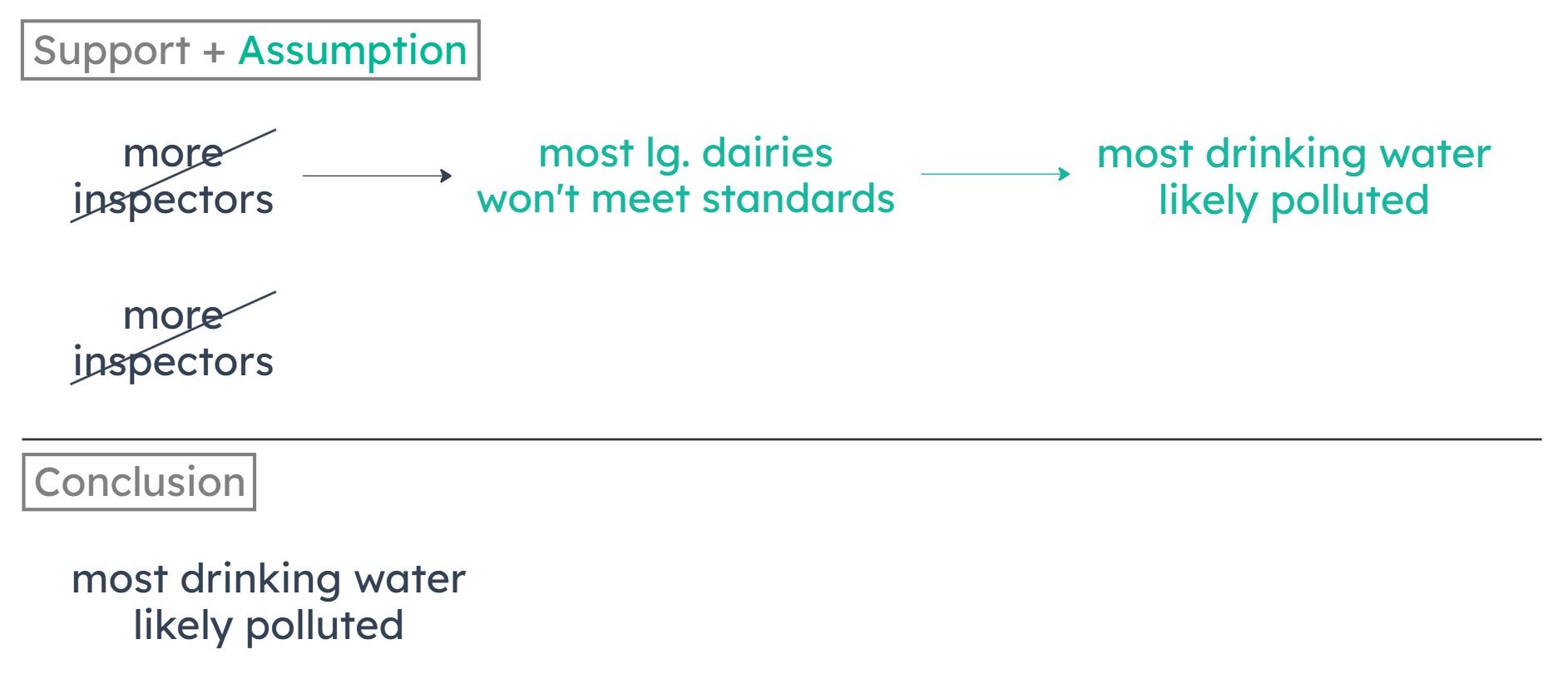

If most large daries in the central valley don’t meet federal standards, then most of the district’s drinking water is likely to be polluted.

A

If most of the dairies in the central valley meet federal standards for the disposal of natural wastes, it is unlikely that most of the district’s drinking water will become polluted.

B

To keep all the drinking water in the district clean requires more dairy inspectors to monitor the dairies’ disposal of natural wastes.

C

All of the district’s drinking water is likely to become polluted only if all of the large dairies in the central valley do not meet federal standards for the disposal of natural wastes.

D

Most of the district’s drinking water is likely to become polluted if most of the large dairies in the central valley do not meet federal standards for the disposal of natural wastes.

E

If none of the large dairies in the central valley meets federal standards for the disposal of natural wastes, most of the district’s drinking water is likely to become polluted.

A science class stored one selection of various fruits at 30 degrees Celsius, a similar selection in similar conditions at 20 degrees, and another similar selection in similar conditions at 10 degrees. Because the fruits stored at 20 degrees stayed fresh longer than those stored at 30 degrees, and those stored at 10 degrees stayed fresh longest, the class concluded that the cooler the temperature at which these varieties of fruits are stored, the longer they will stay fresh.

Summarize Argument

The class concludes that the colder the storage conditions for these fruits, the longer they will stay fresh. They support this with an experiment in which similar fruits were stored at 30, 20, and 10 degrees in similar conditions. The fruits at 20 degrees lasted longer than those at 30 degrees, and the ones at 10 degrees stayed fresh the longest.

Identify and Describe Flaw

The class’s reasoning is flawed because they draw a broad conclusion based on a small range of temperatures (10-30 degrees). They assume that colder storage always keeps the fruits fresh for longer, ignoring the possibility that there could be temperatures that are too cold. In other words, just because the fruits lasted longer at 10 degrees than at 30 doesn’t mean they’ll last longer at 0 degrees.

A

generalized too readily from the fruits it tested to fruits it did not test

This is the cookie-cutter flaw of hasty generalization. The class doesn't make a generalization about fruits that they did not test. Instead, they draw a conclusion about “these varieties of fruits,” meaning the fruits that they did test.

B

ignored the effects of other factors such as humidity and sunlight on the rate of spoilage

The class doesn’t mention other factors, but it doesn’t need to because the experiment controlled for them. By keeping the other conditions similar for each selection of fruits, the class tested the effect of temperature.

C

too readily extrapolated from a narrow range of temperatures to the entire range of temperatures

The experiment showed that within the narrow range of 10-30 degrees, colder storage keeps the fruits fresh longer. They then apply this to all temperatures, assuming that colder storage always works, without considering that some temperatures might be too cold.

D

assumed without proof that its thermometer was reliable

The class never mentions a thermometer at all. Even if they did, we have no reason to believe that the thermometer might be unreliable. The flaw in the class’s argument has to do with how they apply their experiment’s findings, not with their thermometer.

E

neglected to offer any explanation for the results it discovered

The class concludes that colder storage helps the fruits last longer; they don't need to explain why. Even if they did explain why, this wouldn’t fix the fact that they apply their results too broadly.