A

It is a hypothesis the argument provides reasons for believing to be presently false.

B

It is a part of the evidence used in the argument to support the conclusion that a well-known view is misguided.

C

It is an observation that the argument suggests actually supports Malthus’s position.

D

It is a general fact that the argument offers reason to believe will eventually change.

E

It is a hypothesis that, according to the argument, is accepted on the basis of inadequate evidence.

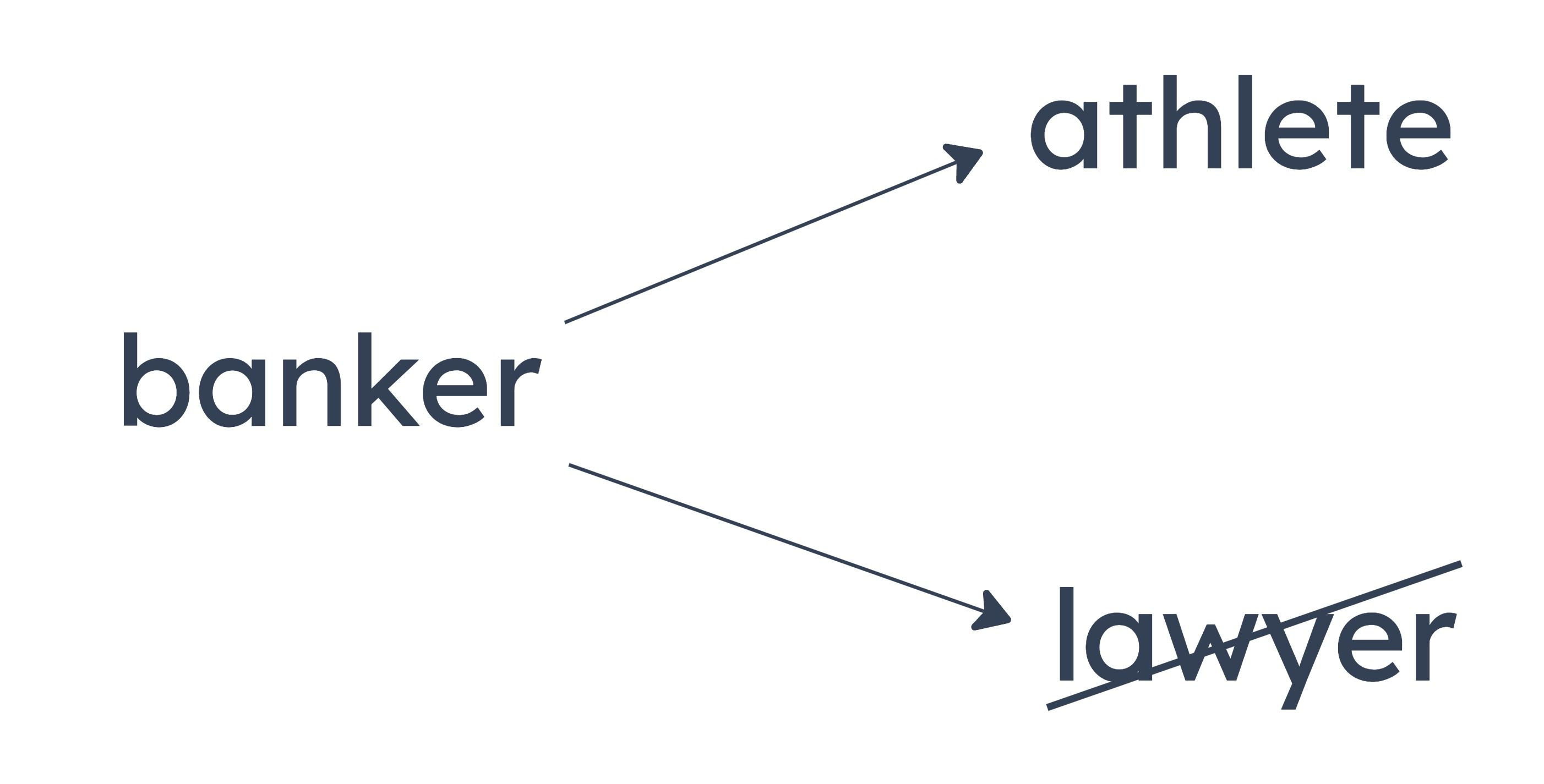

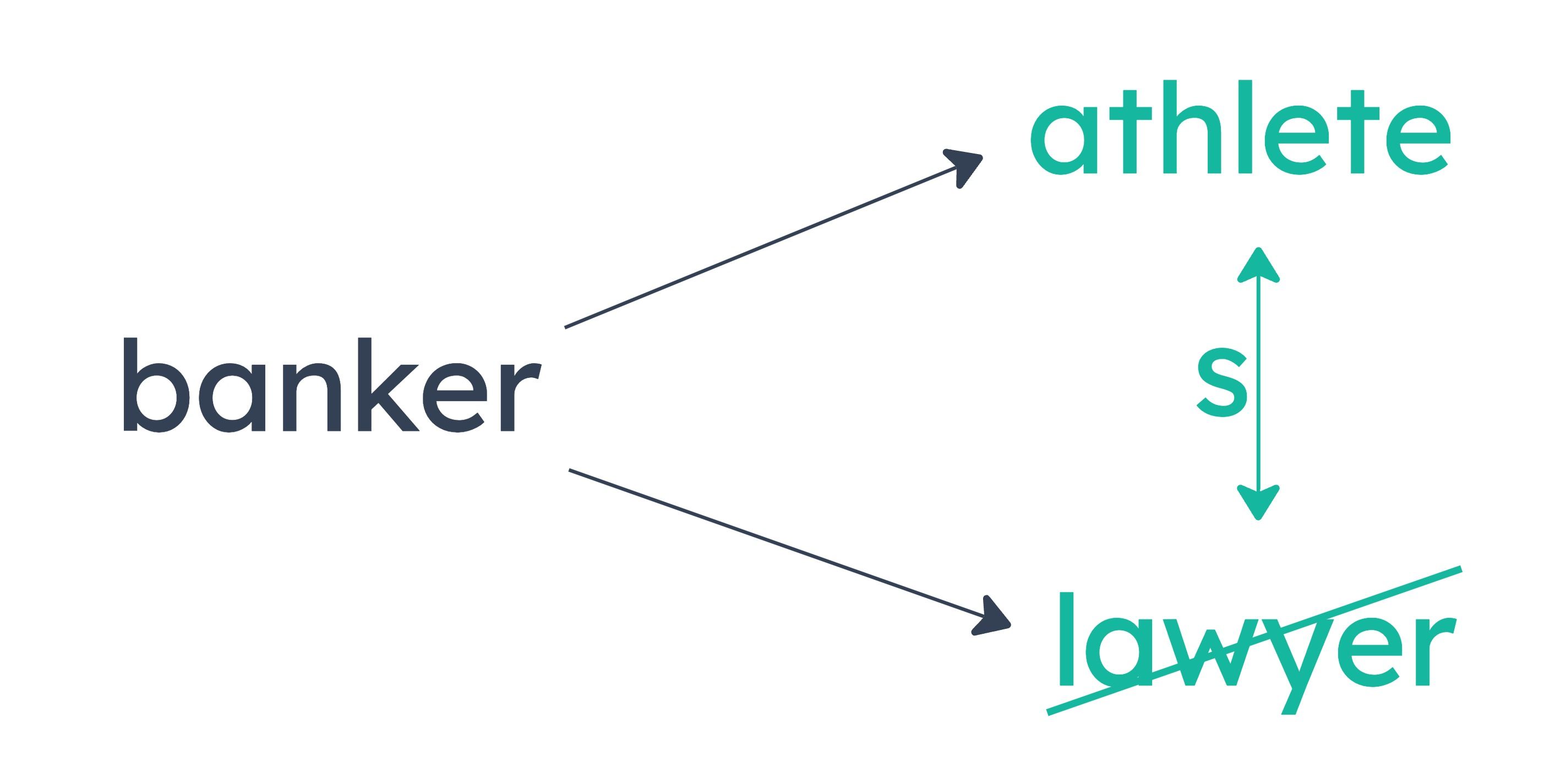

Some of the people who are not lawyers are athletes.

A

All of the athletes are bankers.

B

Some of the lawyers are not athletes.

C

Some of the athletes are not lawyers.

D

All of the bankers are lawyers.

E

None of the lawyers are athletes.

We have an MBT question which we can glean from the question stem which reads: If the statements above are true, which one of the following statements must also be true?

We’re told there are 3 sets of people at this gathering: bankers, athletes, and lawyers. Sounds like a pretty nice gathering! Then we get a pair of very straightforward conditional statements that we can map out: Bankers→Athletes and Lawyers→/Bankers. So what do we know about our three categories of attendees? If you’re a banker then you are definitely an athlete and you are definitely not a lawyer. If you are a lawyer you are definitely not a banker. And if you’re an athlete—well, we don’t know much. We know that all bankers are athletes, and therefore some athletes are bankers. We can’t say anything more than that.

This question is a test of your ability to understand conditional logic. There’s not much more to break down about this stimulus. I suppose we could spend more time asking questions about this gathering—where is it being held? Who are these hybrid banker/athletes? What are these titans of industry and sport gathering to discuss? But that’s not really what you’re here to learn about, so let’s move onto the answer choices:

Answer Choice (A) We know all the bankers are athletes, but if you know your conditional rules, you know that we can’t simply flip this around without negating both sides. This is a very simple case of sufficiency/necessity confusion. Case closed! Moving on.

Answer Choice (B) We know that none of the lawyers are bankers. Other than that, we have no information to go off of. This is wholly unsupported.

Correct Answer Choice (C) Here we go! If you think back to our analysis of the stimulus we concluded that some athletes are bankers. What do we know about bankers? They are definitely not lawyers. Therefore some athletes are not lawyers. Simple as that!

Answer Choice (D) This is just the opposite of what we know to be true. No bankers are, in fact, lawyers.

Answer Choice (E) We don’t know anything about the relationship between lawyers and athletes so we cannot conclude anything about whether there are or are not any lawyers who are athletes.

The Question Stem reads: On the basis of their statements, Price and Albrecht are committed to disagreeing about whether __. This is an Explicit PAI Disagree Question.

Our job here is to evaluate where Price and Albrecht's statements directly contradict each other. Because the question stem does not say "suggests" or "supports," we should be able to find their disagreement directly in the text. Price claims that a corporation has primary responsibility to its shareholders. Why? He offers the Premise that they are the most important constituency because they take the greatest risk. OK. So Price's reasoning is that because the shareholders take on the largest amount of risk, the corporation should keep the shareholder's best interest in mind first when making decisions. He then supports that Premise by saying that if the company were to fail, the shareholders would lose their investment (as seasoned 7Sagers, you'll likely identify that this argument could be better. We need to include a link between risk and responsibility). OK, so now that we know what Price has to say, we need to turn to Albrecht. So a quick recap 1.) A company’s primary responsibility is to shareholders, 2.) because shareholders take on greatest risk, 3.) since if a corporation goes bankrupt, shareholders lose the investment. Albrecht might disagree with any of these claims. Let's see what he has to say.

Albrecht says that shareholders typically have diversified investment portfolios, meaning shareholders are generally invested in multiple companies. This claim suggests that shareholders generally won't lose all their money if one company goes bankrupt. Therefore, they actually are not assuming that much risk. However, our question is explicit, so our job is to see if Albrecht's claim directly contradicts anything Price had to say; currently, it does not. Price then goes on to say that employees' livelihoods are tied to the company and that the well-being of the company has a direct effect on their lives. Albrecht concludes that a corporation's primary responsibility should be to the employees. Bingo. That directly contradicts Price's claim that the primary responsibility is to shareholders. Price and Albrecht disagree on who the corporation's primary responsibility should be, too, because they disagree on who has more at stake. Now it's time to go hunting.

We see that disagreement in Correct Answer Choice (D). Price would agree that shareholders have more at stake than anyone else. That is why Price thinks the company is primarily responsible to the shareholders. Albrecht would disagree. He believes that the employees have more at stake because the company represents their livelihood.

Answer Choice (A) is tricky because both Price and Albrecht are concerned with primary responsibility. However, it is entirely possible for corporations to have more than one responsibility. Albrecht might agree that corporations have a responsibility to their shareholders, butIt's just not their primary responsibility.

Answer Choice (B) is very similar to (A). Price might agree that corporations are responsible for the welfare of their employees, but the corporation's primary responsibility is to their shareholders.

Answer Choice (C) is wrong because we have no idea where Price or Albrecht land on this.

Answer Choice (E) is wrong because both Albrecht and Price would likely agree with this statement. Earlier, we mentioned how Albrecht claimed that shareholders typically have diversified portfolios, which suggested that a corporation failing wouldn't be a big deal. However, he uses the word "typically," which indicates that might not always be the case. He might also believe that some investors would be destroyed by a single company failing. Since it’s likely that both Price and Albrecht agree, we can eliminate this answer choice.

The question stem reads: The reasoning in the scientist’s argument is most vulnerable to criticism on grounds that the argument… This is a Flaw question.

The scientist claims to have discovered that several years of atmospheric pollution during the 1500s coincided with a period of relatively high global temperatures. The scientist concludes, in this case (the period during the 1500s), that atmospheric pollution caused the global temperature to rise.

Right off the bat, we can see that the scientist has taken a correlation to mean causation. Sure atmospheric pollution coincided with higher global temperature, but perhaps the higher global temperature caused the pollution. Perhaps both were derivative effects of the same cause! As a scientist, they really should know better.

Answer Choice (A) is incorrect. The scientist has nothing to say about whether or not rising global temperatures are harmful.

Answer Choice (B) is incorrect. The scientist has not drawn a general rule. He says that atmospheric pollution caused global temperatures to rise in this case. Even if the scientist drew a general rule, we wouldn’t know whether the 1500s were likely or unlikely to be representative.

Answer Choice (C) is incorrect. (C) is very similar to (B). We can rule (C) out because the scientist did not draw a general rule.

Answer choice (D) is incorrect. Sure, we have to assume that the data methods are reliable, but that is not a flaw in reasoning.

Correct Answer Choice (E) is what we discussed. The author has assumed that the correlation between atmospheric pollution and the rising global temperature of the 1500s implies that atmospheric pollution caused the temperatures to rise.

This stimulus starts with Gilbert’s conclusion: the food label is mistaken. We then get his premise: the label says that the cookie has only natural ingredients but the alpha hydroxy acids (AHAs) contained in the cookies are produced synthetically at the cookie plant.

We then get Sabina’s argument. Again we start with her conclusion: the label is, in fact, not mistaken. She goes on to explain in her premise: AHA can also occur naturally in sugarcane.

Basically this boils down to the question of how you define natural ingredients. Is an ingredient natural if it can occur naturally as Sabina argues, or does it matter how the ingredient in question was produced, as Gilbert contends? The answer choice we’re looking for seems like it may resemble a sufficient assumption or PSA rule that will make Sabina’s argument valid. Let’s take a look:

Answer Choice (A) This is irrelevant. What we are concerned with is whether this particular label for these particular cookies is mistaken. If we look at Gilbert’s argument he tells us everything we need to know: we are talking about a particular batch of cookies that do contain AHA and we are discussing whether AHA constitutes a natural ingredient.

Answer Choice (B) Another irrelevant answer choice. We are only concerned with AHA, which we know is part of the cookies. Whether or not other chemicals don’t make it into the final batch doesn’t affect our argument.

Answer Choice (C) Again, we are concerned with this particular label for these particular cookies. This is irrelevant information.

Answer Choice (D) This doesn’t mean that Sabina is correct, it just means that other companies could be repeating similar falsehoods. What we are concerned with is whether or not the claims in question are accurate.

Correct Answer Choice (E) This is exactly what we need. It tells us that all substances (except those that don’t occur naturally in any source) are considered natural. What do we know about AHA? For one, it can be found occurring naturally in sugarcane. Therefore, it is included in the set of substances that can be considered natural. If it’s considered natural, what does that tell us about Sabina’s argument? It’s valid! Remember how I said we might be looking for something that resembles a PSA rule. Well here we have it! Her premise triggers this rule, which leads us directly to her conclusion: that the label which includes AHA in a set of all-natural ingredients is not mistaken.