Summary

Some people prefer to avoid facing unpleasant truths. These people resent those who force them into a confrontation with unwanted honesty. Other people dislike having any information withheld from them, including painful information.

Strongly Supported Conclusions

If people who prefer to avoid facing unpleasant truths are guided by the directive to treat others how they would want to be treated, they would withhold painful information from those who want all information given to them.

A

they will sometimes withhold comment in situations in which they would otherwise be willing to speak

This is unsupported because we don’t know in which situations members of the former group would usually be willing to speak.

B

they will sometimes treat those in the latter group in a manner the members of this latter group do not like

This is strongly supported because those in the former group, who wish to have painful information withheld, would do the same and withhold painful information from the latter group. The latter group does not like having any information withheld.

C

those in the latter group must be guided by an entirely different principle of behavior

This is unsupported because we don’t know what principles of behavior guide those in the latter group.

D

those in the latter group will respond by concealing unpleasant truths

This is unsupported because we don’t know that the latter group would reciprocate if the former group started withholding painful truths.

E

the result will meet with the approval of both groups

This is anti-supported because if the former group treated the latter how the former would want to be treated, then the former group would withhold painful information to the dismay of the latter group.

Summarize Argument: Phenomenon-Hypothesis

The advocate argues that taking cold medicine is counterproductive. She supports this claim by citing a study wherein people who took cold medicine reported more severe symptoms than did those who didn’t take cold medicine.

Identify and Describe Flaw

This is a “correlation doesn’t imply causation” flaw, where the advocate sees a correlation and concludes that one thing caused the other without ruling out alternative hypotheses. Specifically, she overlooks two key alternatives:

(1) The causal relationship could be reversed—maybe people with more severe symptoms are more likely to take cold medicine!

(2) Some other factor could be causing the correlation—for example, maybe in parts of the world where colds tend to be more severe, cold medicine also happens to be more widely available.

(1) The causal relationship could be reversed—maybe people with more severe symptoms are more likely to take cold medicine!

(2) Some other factor could be causing the correlation—for example, maybe in parts of the world where colds tend to be more severe, cold medicine also happens to be more widely available.

A

treats something as true simply because most people believe it to be true

The advocate’s premise is a study, not a general belief. Furthermore, we have no reason to think that most people believe her conclusion or her premise to be true.

B

treats some people as experts in an area in which there is no reason to take them to be reliable sources of information

The advocate doesn’t arbitrarily treat anyone as an expert. Rather, she cites the results of a study wherein people reported on their own symptoms—a subject in which people do have some expertise!

C

takes something to be true in one case just because it is true in most cases

The advocate’s conclusion is extremely general; she does not mention any specific cases.

D

rests on a confusion between what is required for a particular outcome and what is sufficient to cause that outcome

The advocate’s argument doesn’t mistake sufficiency for necessity. She doesn’t claim in either the premise or the conclusion that cold medicine is sufficient or necessary to cause severe cold symptoms.

E

confuses what is likely the cause of something for an effect of that thing

This is the cookie-cutter flaw of confusing correlation and causation. The advocate’s argument forgets that the causal relationship could be reversed—maybe people with more severe symptoms are more likely to take cold medicine!

Summarize Argument

The author concludes that children have a good grasp on what’s real versus what’s pretend. For one thing, they can demonstrate their understanding if asked directly. For another, their make-believe games rely on being able to tell real and pretend apart.

Identify Conclusion

The conclusion is about how children think: “Children clearly have a reasonably sophisticated understanding of what is real and what is pretend.”

A

Children apparently have a reasonably sophisticated understanding of what is real and what is pretend.

Make-believe wouldn’t work without a good grasp on what’s real and what’s pretend, and children can tell the two apart if asked. Thus, children have a sophisticated understanding of what’s real and what’s pretend.

B

Children who have acquired a command of language generally answer correctly when asked about whether a thing is real or pretend.

This is a premise that supports the author’s argument. If children can answer correctly whether something is real or not, they clearly have a good understanding of real versus pretend.

C

Even a very young child can tell the difference between a lion and someone pretending to be a lion.

This is an example of children doing make-believe. Since they’re able to tell the difference between a pretend, fun lion and a real, terrifying lion, they must have a good grasp on what’s real and what’s pretend.

D

Children would be terrified if they believed they were in the presence of a real lion.

This supports the conclusion. Since children aren’t terrified in the presence of a pretend lion, they must know it isn’t real. Therefore, they have a good grasp on real versus pretend.

E

The pleasure children get from make-believe would be impossible to explain if they could not distinguish between what is real and what is pretend.

This premise supports the author’s conclusion. Since children are able to get pleasure from make believe, they must know what’s real and what’s pretend.

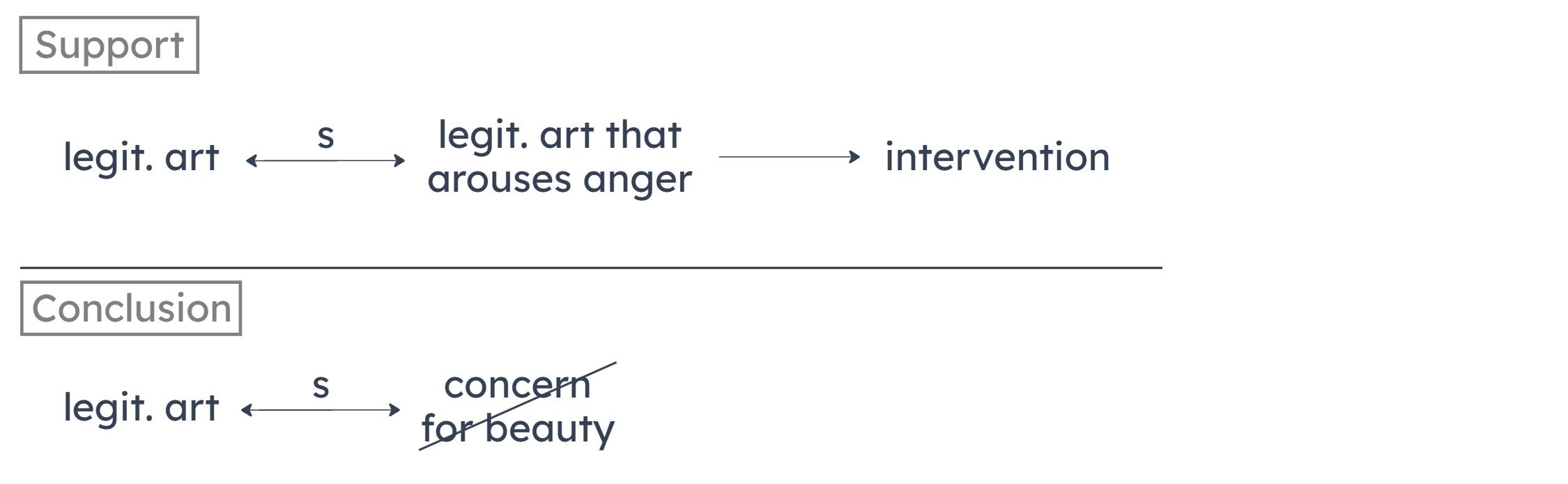

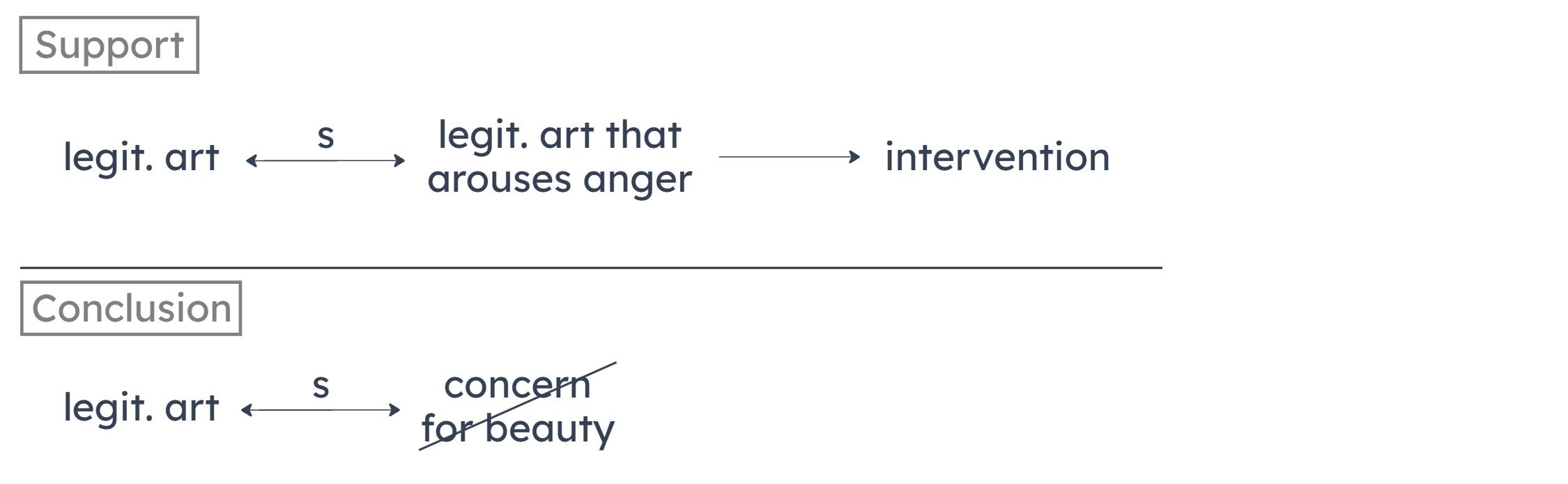

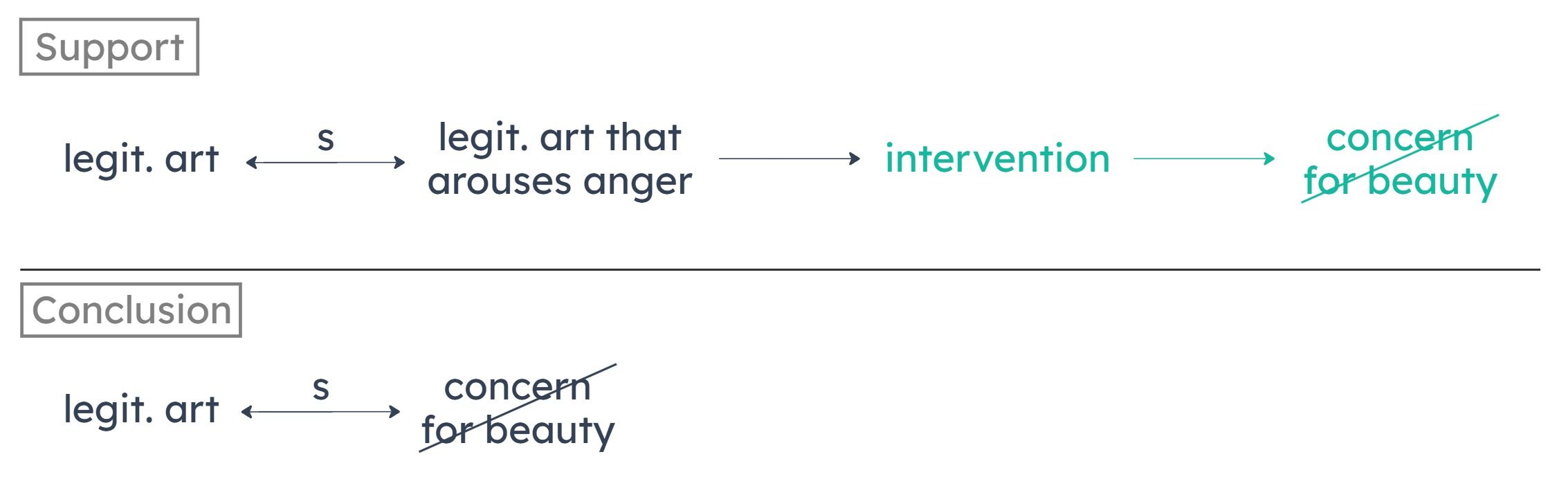

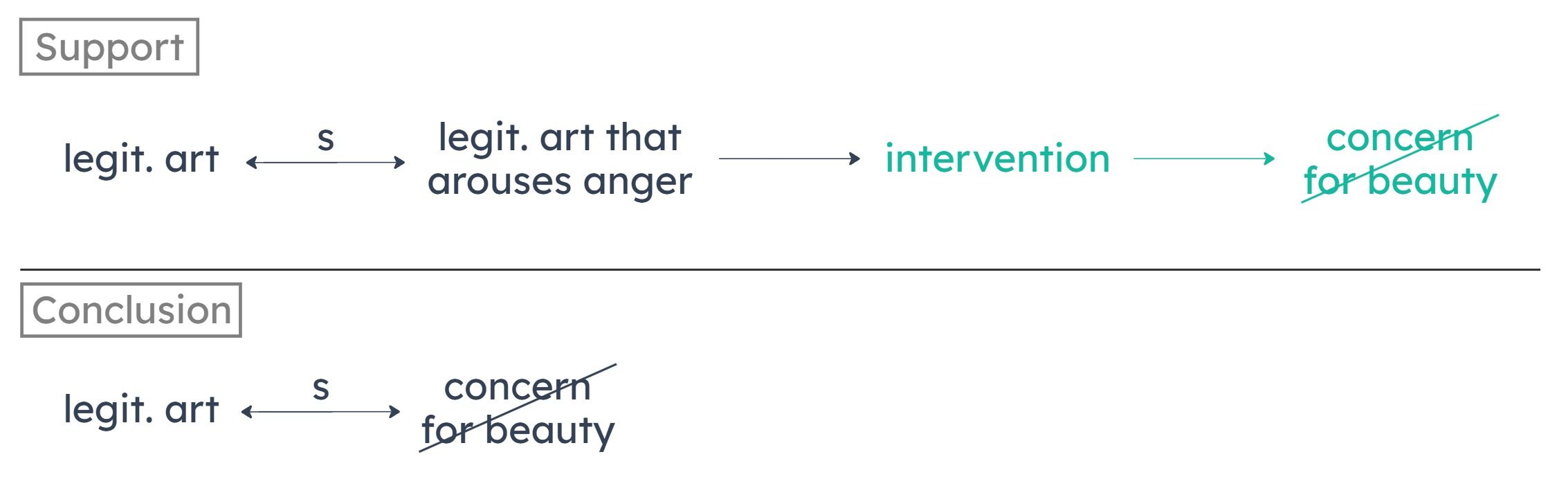

Summary

The author concludes that some legitimate art is not concerned with beauty. Why? Because of the following:

Some legitimate art aims to arouse anger.

All legitimate art with the aim of arousing anger intentionally calls for concrete intervention.

Some legitimate art aims to arouse anger.

All legitimate art with the aim of arousing anger intentionally calls for concrete intervention.

Missing Connection

The conclusion asserts that some legitimate art isn’t concerned with beauty. But the premises don’t tell us anything about what’s not concerned with beauty. So, at a minimum, we know that the correct answer should allow us to establish that something is not concerned with beauty.

To go further, we can anticipate some specific relationships that could get us from the premise to the concept “not concerned with beauty.” We know from the premises that some legitimate art aims to arouse anger. We also know that some legitimate art calls for concrete intervention. Either of these could make the argument valid:

Any art that aims to arouse anger is not concerned with beauty.

Any art that calls for concrete intervention is not concerned with beauty.

To go further, we can anticipate some specific relationships that could get us from the premise to the concept “not concerned with beauty.” We know from the premises that some legitimate art aims to arouse anger. We also know that some legitimate art calls for concrete intervention. Either of these could make the argument valid:

Any art that aims to arouse anger is not concerned with beauty.

Any art that calls for concrete intervention is not concerned with beauty.

A

There are works that are concerned with beauty but that are not legitimate works of art.

(A) tells us that there are some works concerned with beauty that aren’t legitimate art. But we’re trying to prove that there are some legitimate artworks that are NOT concerned with beauty. Learning about works that ARE concerned with beauty doesn’t help us prove that certain works are NOT concerned with beauty.

B

Only those works that are exclusively concerned with beauty are legitimate works of art.

(B) asserts that in order to be legitimate, a work must be exclusively concerned with beauty. But we’re trying to prove that there are legitimate works that are NOT concerned with beauty. (B) contradicts our conclusion.

C

Works of art that call for intervention have a merely secondary concern with beauty.

(C) establishes that art that calls for intervention has a “secondary” concern with beauty. But we want to establish that some of these works are NOT concerned with beauty. Having a secondary concern with beauty does not imply NO concern with beauty.

D

No works of art that call for intervention are concerned with beauty.

(D) asserts that if a work of art calls for intervention, then it’s not concerned with beauty. Since we know some legitimate art calls for intervention, (D) allows us to conclude that some legitimate art is not concerned with beauty.

E

Only works that call for intervention are legitimate works of art.

(E) doesn’t establish what kind of art is not concerned with beauty. Since neither this answer nor the premises tell us what kind of art is not concerned with beauty, there’s no way (E) can make the argument valid.