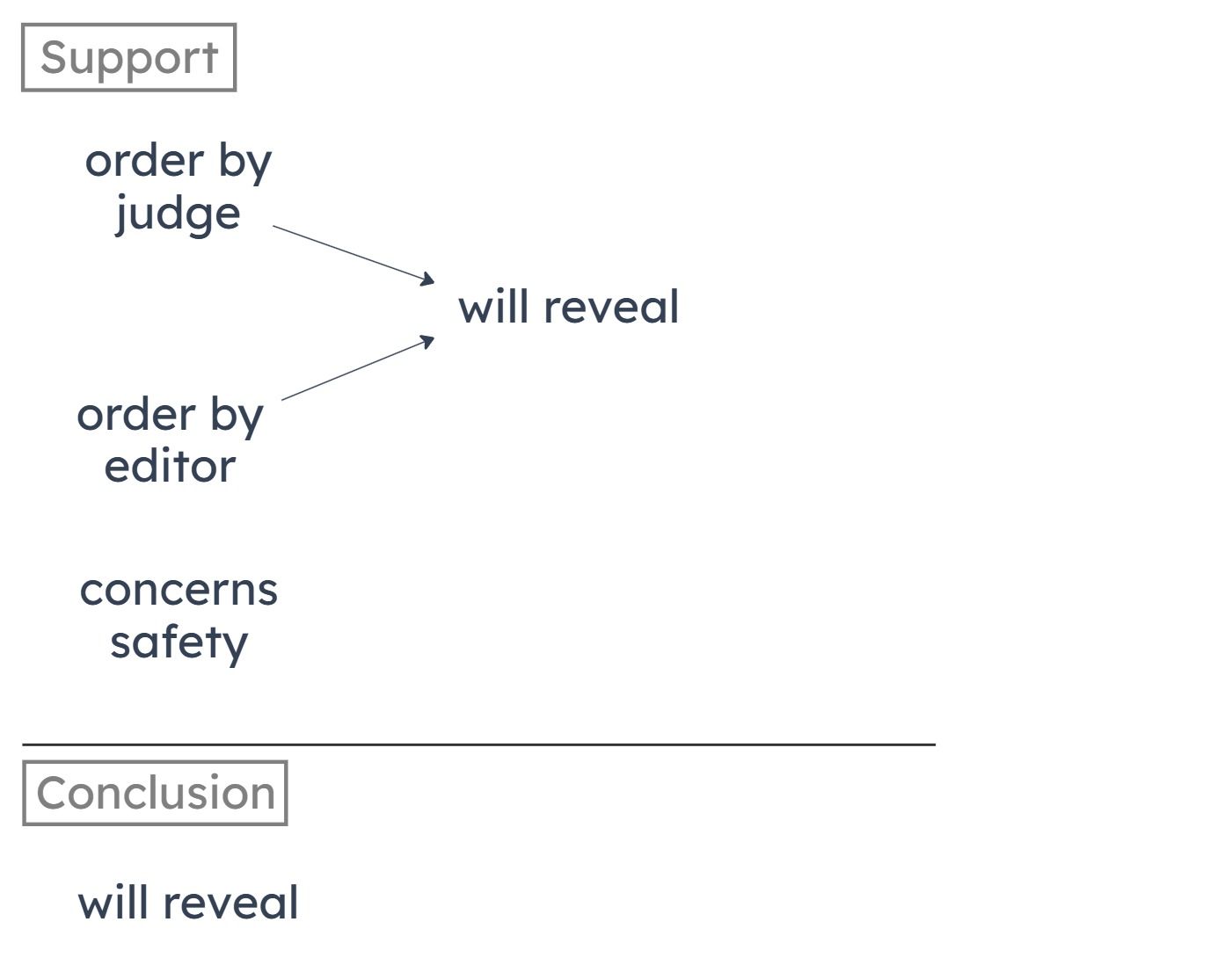

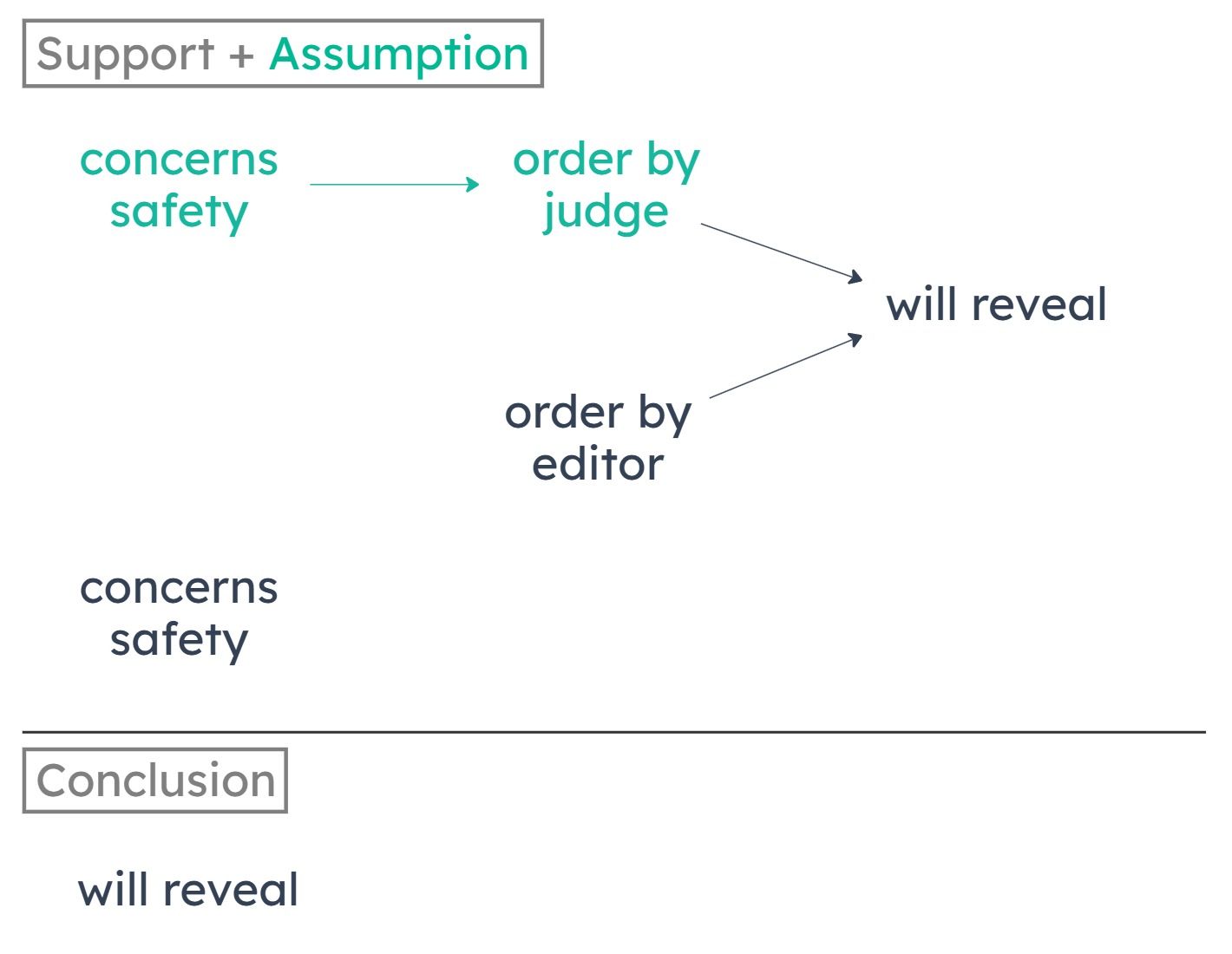

If she is ordered to do so by a judge or by her editor, the journalist will publicly reveal the informant’s identity.

The information provided by the informant concerns safey violations at the power plant.

A

The information that the informant provided is known to be false.

B

The journalist’s editor will not order her to reveal the informant’s identity unless the information is accurate and concerns public safety.

C

If the information concerns safety at the power plant, a judge will order the journalist to reveal her informant’s identity.

D

The truth of the information provided by the informant can be verified only if the informant’s identity is publicly revealed.

E

The informant understood, at the time the journalist promised him confidentiality, that she would break this promise if ordered to do so by a judge.

A

The 2009 analysis revealed that cobalt was located only in the topmost paint layer, which was possibly applied to conceal damage to original paint layers.

B

The 2009 analysis used sophisticated scientific equipment that can detect much smaller amounts of cobalt than could the equipment used for the 1955 analysis.

C

The 2009 analysis took more samples from the painting than the 1955 analysis did, though those samples were smaller.

D

Many experts, based on the style and the subject matter of the painting, have dated the painting to the 1700s.

E

New information that came to light in the 1990s suggested that cobalt blue was used only rarely in Italy in the years immediately following 1804.

The author also assumes that the measures encouraged by the campaign are effective against the spread of influenza, so that the public’s following of those measures could cause the lower rates.

A

The incidence of food-borne illnesses, which can be effectively controlled by frequent hand washing, was markedly lower than usual during the six-month period.

B

During the six-month period, the incidence of the common cold, which has many of the same symptoms as influenza, was about the same as usual.

C

There were fewer large public gatherings than usual during the six-month period.

D

Independently of the public health campaign, the news media spread the message that one’s risk of contracting influenza can be lessened by frequent hand washing.

E

In a survey completed before the campaign began, many people admitted that they should do more to limit the spread of influenza.

A

In general, a meeting at the company that is no more than 30 minutes long and has a clear time frame will achieve maximum productivity.

B

Most meetings at the company show diminishing returns after 30 minutes, according to a study.

C

A meeting at the company will be maximally productive only if it has a clear time frame and lasts no more than 30 minutes.

D

According to a study, meetings at the company were the most productive when they had clear time frames.

E

A study of meetings at the company says that little productivity should be expected after the 60-minute mark.

Nutritionist: Most fad diets prescribe a single narrow range of nutrients for everyone. But because different foods contain nutrients that are helpful for treating or preventing different health problems, dietary needs vary widely from person to person. However, everyone should eat plenty of fruits and vegetables, which protect against a wide range of health problems.

Summary

Most fad diets prescribe a narrow range of nutrients for everyone. But dietary needs vary widely from person to person because different foods have different nutrients for treating and preventing different health problems. However, everyone should eat plenty of fruits and vegetables because these foods protect against a range of health problems.

Strongly Supported Conclusions

Most fad diets do not meet the dietary needs of at least some people.

A

Most fad diets require that everyone following them eat plenty of fruits and vegetables.

This answer is unsupported. We don’t know what specifically most fad diets require. We only know that most fad diets prescribe a narrow range of nutrients.

B

Fruits and vegetables are the only foods that contain enough different nutrients to protect against a wide range of health problems.

This answer is unsupported. Saying these are the “only” foods with these characteristics is too strong. We only know that fruits and vegetables are an example of a food group containing a diversity of nutrients.

C

Any two people have different health problems and thus different dietary needs.

This answer is unsupported. It is possible that you could have two people with the same health problems.

D

Most fad diets fail to satisfy the dietary needs of some people.

This answer is strongly supported. We know that the dietary needs of people vary widely and that most fad diets prescribe a narrow range of nutrients. It’s inevitable that most fad diets don’t meet some people’s dietary needs.

E

There are very few if any nutrients that are contained in every food other than fruits and vegetables.

This answer is unsupported. We don’t know what nutrients are contained in other foods.