A

because some works of art are nonrepresentational, there is no way of judging our aesthetic experience of them

B

an object may have some aesthetic properties and not be a work of art

C

aesthetically relevant properties other than representation can determine whether an object is a work of art

D

some works of art may have properties that are not relevant to our aesthetic experience of them

E

some objects that represent things other than themselves are not works of art

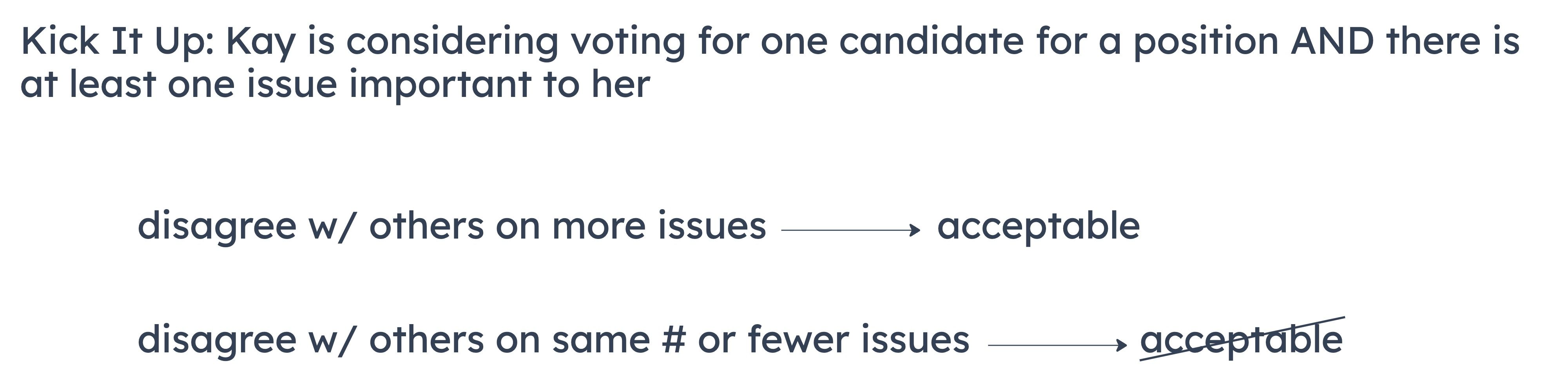

A

If there are no issues important to her, it is unacceptable for her to vote for any candidate in the election.

B

If she agrees with each of the candidates on most of the issues important to her, it is unacceptable for her to vote for any candidate in the election.

C

If she agrees with a particular candidate on only one issue important to her, it is unacceptable for her to vote for that candidate.

D

If she disagrees with each of the candidates on exactly three issues important to her, it is unacceptable for her to vote for any candidate in the election.

E

If there are more issues important to her on which she disagrees with a particular candidate than there are such issues on which she agrees with that candidate, it is unacceptable for her to vote for that candidate.

A

concluding that since an expected consequence of a supposed development did not occur, that development itself did not take place

B

concluding that since only one of the two predictable consequences of a certain kind of behavior is observed to occur, this observed occurrence cannot, in the current situation, be a consequence of such behavior

C

arguing that since people’s economic behavior is guided by economic self-interest, only misinformation or error will cause people to engage in economic behavior that harms them economically

D

arguing that since two alternative developments exhaust all the plausible possibilities, one of those developments occurred and the other did not

E

concluding that since the evidence concerning a supposed change is ambiguous, it is most likely that no change is actually taking place

Which one of the following inferences is most supported by the passage?

This is a Most Strongly Supported question.

Vitamin XYZ has long been a favorite among health food enthusiasts.

Forget about vitamins with only 1 letter. Vitamin B? Vitamin D? Get out of here. You need vitamin XYZ.

In a recent large study, those who took large amounts of vitamin XYZ daily for two years showed on average a 40 percent lower risk of heart disease than did members of a control group.

This sentence gives us something very common on the LSAT, and something very uncommon. What’s common is that we get a correlation between taking vitamin XYZ daily and having a significantly lower risk of heart disease. What’s uncommon is that the stimulus gives us something closer to the ideal experiment than we typically see. This is a large study, with a control group, showing a large effect size (40 percent). All three are features that will help to establish a causal explanation of the results: that the reduction of heart disease risk is because of vitamin XYZ.

At this point, I only see one potential failing of this experiment: we don’t yet know whether the people in the control group are similar to the people in the vitamin XYZ group in features that could affect rates of heart disease. In other words, was group assignment randomized? Let’s keep reading the stimulus.

Researchers corrected for differences in relevant habits, such as diet.

Unclear whether the group assignment was randomized, but these researchers do know what they’re doing. They’ve controlled for “differences in relevant habits” – that gets rid of a whole host of potential alternate causes for the correlation between vitamin XYZ and lower risk of heart disease. Exercise habits? That was controlled for. Eating fatty foods? That was controlled for. There’s still some things that aren’t controlled for, such as the genetics of the two groups. It’s possible that the control group might just, by coincidence, be more genetically vulnerable to heart disease than the vitamin XYZ group. Possible, but not very likely, and we don’t have any reason to think this might have happened.

So what can we have in mind before going to the answers? We got some pretty strong evidence of a causal relationship between vitamin XYZ and lower heart disease. The fact that there was a control group and the researchers controlled for other factors relevant to heart disease is what makes the evidence strong.

Answer Choice (A) Taking large amounts of vitamins is probably worth risking the side effects.

There are at least three issues with (A). First, the idea of “worth” is a prescriptive claim, or in other words, involves a value judgment. But we don’t know from the stimulus how to tell what’s worth anything – there’s no standard we can use to say whether vitamins are worth risking the side effects. Second, what “side effects?” The stimulus contained no information about side effects. Hence, we cannot do acost-benefit analysis. Third, the claim in this answer is about “all vitamins” but the stimulus only talked about vitamin XYZ. If we generalize from one specific vitamin to all vitamins, we will have committed the reasoning flaw of making a hasty generalization.

Correct Answer Choice (B) Those who take large doses of vitamin XYZ daily for the next two years will exhibit on average an increase in the likelihood of avoiding heart disease.

This prediction is supported by the stimulus because evidence of causation is strong. (B) matches up with what we were told about the vitamin XYZ group – it’s about taking large amounts of vitamin XYZ daily for two years. (B) also avoids over-generalizing by not saying that everyone will avoid heart disease or that most people will avoid heart disease. It says instead that the group of vitamin-takers will “on average” have an increased likelihood of avoiding heart disease. That’s moderate enough to be supported on this evidence.

Answer Choice (C) Li, who has taken large amounts of vitamin XYZ daily for the past two years, has a 40 percent lower risk of heart disease than she did two years ago.

This answer is far less supported than (B), because it’s about an individual person. Strong evidence of correlation can provide evidence of cause, but this works only on the level of group averages.

For example, we know that smoking causes lung cancer. But does that mean that every single person who smokes will develop lung cancer? No. There are many causal forces at play. Some, e.g., better genetics, may push against getting lung cancer.

So in this case, we just don’t know whether Li will have a reduced risk of heart disease. Maybe she won’t get that kind of benefit because of her genetics or her lifestyle habits?

In addition, the stimulus specifically said that the vitamin XYZ group showed “on average a 40 percent lower risk of heart disease.” That means the 40 percent figure is an average – that doesn’t mean that each individual person in the group experienced a 40 percent decrease in their risk of heart disease. If one person had a decrease of 30 percent and another person a decrease of 50 percent, that produces a 40 percent average (if those were the only 2 people in the group).

Answer Choice (D) Taking large amounts of vitamin XYZ daily over the course of one’s adult life should be recommended to most adults.

There are at least three issues with this answer.

First, we don’t want to overlook the potential negative effects of taking vitamin XYZ. Just because there’s evidence vitamin XYZ seems to reduce risk of heart disease, that doesn’t mean that people should take it. What if vitamin XYZ has side effects that make one more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease or dementia?

Second, this answer contains the prescriptive word “should.” It’s telling people what they should do. But the stimulus doesn’t give us any standard by which we can know what people should do. Is a lower risk of heart disease something that most people should try to achieve? I think so and you’d probably agree. But that’s not a position that the stimulus supports.

Third, the experiment in the stimulus showed positive results after the participants took these vitamins for two years. We cannot infer that results will still be positive if they take them “over the course of one’s adult life.”

Answer Choice (E) Health food enthusiasts are probably correct in believing that large daily doses of multiple vitamins promote good health.

The study specifically examines the effects of vitamin XYZ on heart disease risk. (E), however, generalizes this to "multiple vitamins" and their impact on "good health" broadly. We cannot assume the effects observed from one particular vitamin to be the same for all vitamins. Likewise, good health encompasses numerous factors beyond heart disease risk, and the study does not provide evidence about the impact (positive or negative) of vitamin XYZ on these other factors.

Moreover, this answer is also wrong when it refers to health food enthusiasts probably being “correct in believing” something. The stimulus doesn’t tell us what health food enthusiasts believe. We know that they seem to like vitamin XYZ – but the stimulus doesn’t say exactly why they like vitamin XYZ, or that they like other vitamins besides XYZ.