Summarize Argument

The newspaper executive concludes that the newspaper is justified in paying its reporters a far-below-average salary. Why? Because the lower pay is compensated by the training the reporters get on the job.

Notable Assumptions

The executive assumes that the training reporters receive while working for the newspaper in question is substantially higher in quality than the training they would receive at a higher-paying competitor. Otherwise, the training couldn’t justify the low salary.

The executive also assumes that the newspaper’s reporters are generally inexperienced enough to benefit from additional training, or that their pay increases after they gain experience.

The executive also assumes that the newspaper’s reporters are generally inexperienced enough to benefit from additional training, or that their pay increases after they gain experience.

A

Senior reporters at the newspaper earned as much as reporters of similar stature who worked for the newspaper’s principal competitors.

This does not weaken the argument. If anything, it strengthens by affirming the executive’s assumption that the pay shortfall is limited to reporters who benefit from additional training.

B

Most of the newspaper’s reporters had worked there for more than ten years.

This weakens the argument by indicating that most of the newspaper’s reporters do not benefit from additional training. That would mean they just get paid less without receiving any benefit in return—in other words, the pay gap would not be justified.

C

The circulation of the newspaper had recently reached a plateau, after it had increased steadily throughout the 1980s.

This does not weaken the argument. The circulation of the newspaper has nothing to do with whether or not the newspaper is justified in paying reporters less. Like (E), this claim is just irrelevant.

D

The union that represented reporters at the newspaper was different from the union that represented reporters at the newspaper’s competitors.

This does not weaken the argument. Having a different union has no bearing on whether the pay difference is justified: maybe the union is weak and failed to negotiate a good deal, or maybe getting more training is actually a great bargain for reporters. We just don’t know.

E

The newspaper was widely read throughout continental Europe and Great Britain as well as North America.

This does not weaken the argument—like (C), it’s just irrelevant. Where the newspapers readers are located has nothing to do with the executive’s argument about lower pay for reporters being justified.

Summary

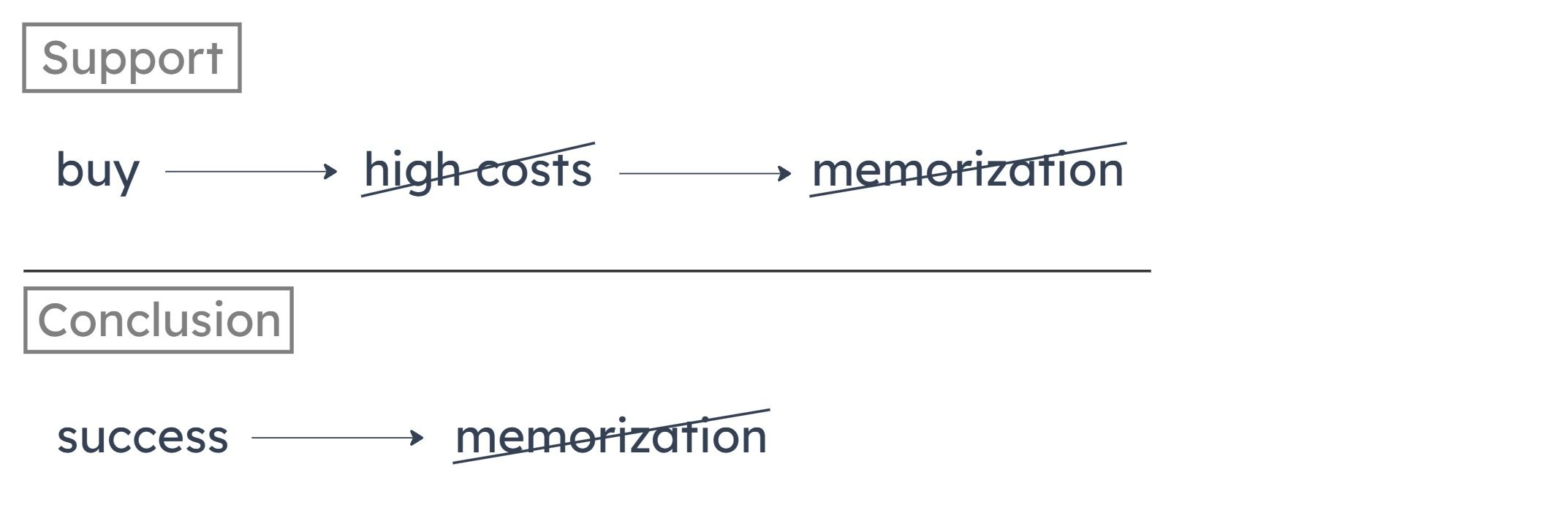

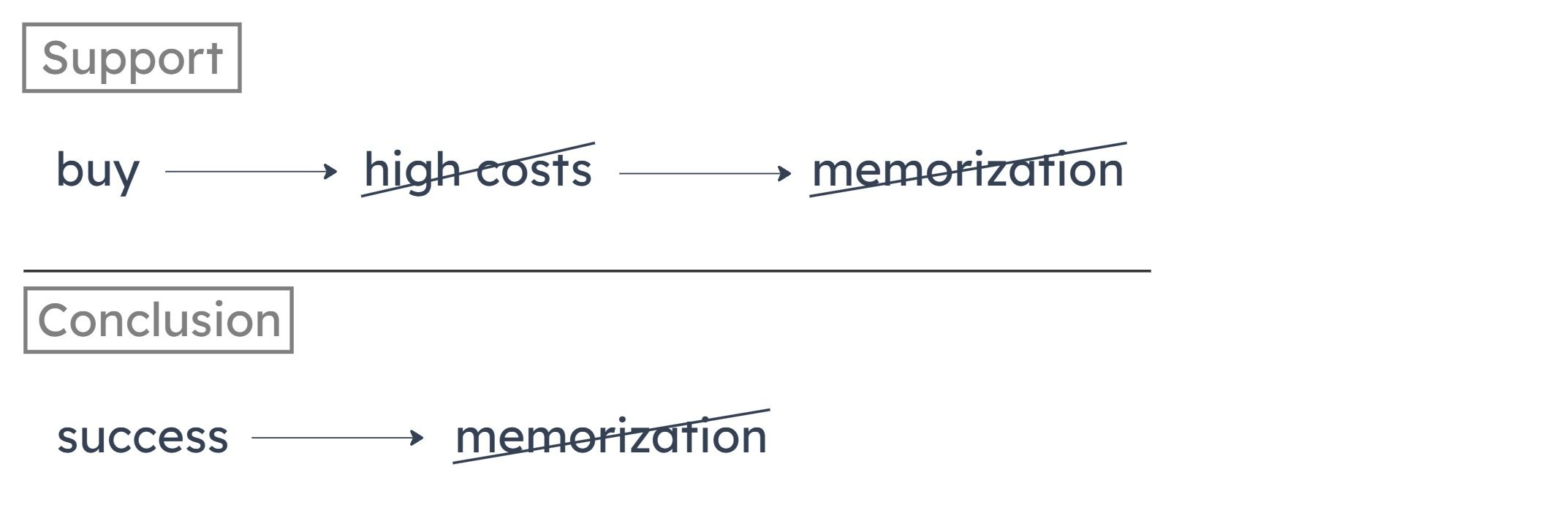

The argument concludes that in order to be successful, the software cannot demand memorization of unfamiliar commands. This is based on the following two premises:

If training costs are high, prime purchasers of the software won’t buy it.

If a software demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, then the training costs are high.

If training costs are high, prime purchasers of the software won’t buy it.

If a software demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, then the training costs are high.

Missing Connection

We want to reach the conclusion that if a software demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, it won’t be successful. “Won’t be successful” is a new concept in the conclusion; the premises don’t tell us what leads to lack of success.

But we do know from the two premises together that if a software demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, the prime purchasers won’t buy it.

If we learn that “prime purchasers won’t buy” establishes “unsuccessful,” that will establish that if a software demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, it won’t be successful. In other words, we want to learn that in order to be successful, a software needs prime purchasers to buy it.

But we do know from the two premises together that if a software demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, the prime purchasers won’t buy it.

If we learn that “prime purchasers won’t buy” establishes “unsuccessful,” that will establish that if a software demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, it won’t be successful. In other words, we want to learn that in order to be successful, a software needs prime purchasers to buy it.

A

If most prime purchasers of computer software buy a software product, that product will be successful.

(A) establishes what is sufficient for a software product to be successful. But we’re trying to establish what’s sufficient for a software product to be UNsuccessful. Or, you could also say that we’re looking for what’s necessary for the product to be successful. Learning what’s sufficient for success doesn’t prove what’s necessary for success.

B

Commercial computer software that does not require users to memorize unfamiliar commands is no more expensive than software that does.

(B) compares the expense of different kinds of software. But it doesn’t tell us anything about what’s required for success, or what’s sufficient to lead to lack of success.

C

Commercial computer software will not be successful unless prime purchasers buy it.

(C) establishes that in order for a software product to be successful, its prime purchasers must buy it. Since we know from the premises that if a product demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, prime purchasers won’t buy it, adding (C) now establishes that if a product demands memorization of unfamiliar commands, it won’t be successful.

D

If the initial cost of computer software is high, but the cost of training users is low, prime purchasers will still buy that software.

(D) doesn’t tell us anything about what’s required for success, or what’s sufficient to lead to lack of success.

E

The more difficult it is to learn how to use a piece of software, the more expensive it is to teach a person to use that software.

(E) doesn’t tell us anything about what’s required for success, or what’s sufficient to lead to lack of success.

Summarize Argument

The author concludes that, when assessing a discipline's scientific value, people should consider that discipline’s blemished origins. He points to chemistry as an example, noting that many important discoveries were made by alchemists, whose superstitions and belief in magic shaped early chemical theory.

Identify and Describe Flaw

The author concludes that people should consider a discipline’s blemished origins when assessing that discipline’s scientific value. But he fails to consider whether those origins are relevant to how the discipline functions today. To use his example, what if chemistry today is entirely different from chemistry as practiced by the alchemists? In that case, why should we consider the alchemists when judging chemistry’s current scientific value?

A

fails to establish that disciplines with unblemished origins are scientifically valuable

The author never assumes that disciplines with unblemished origins are scientifically valuable. He just argues that blemished origins should be considered when assessing a discipline’s scientific value.

B

fails to consider how chemistry’s current theories and practices differ from those of the alchemists mentioned

The author fails to consider the possibility that alchemists’ practices are entirely different from current chemistry practices and so perhaps should not be considered when assessing chemistry’s scientific value.

C

uses an example to contradict the principle under consideration

The author does use an example, but he uses it to support the principle under consideration, not to contradict it.

D

does not prove that most disciplines that are not scientifically valuable have origins that are in some way suspect

The author never assumes that disciplines that are not valuable have suspect origins, so he doesn’t need to prove this. He doesn’t say how a discipline’s origins affect its scientific values, only that its origins should be considered when assessing its value.

E

uses the word “discipline” in two different senses

This is the cookie-cutter flaw of “equivocation.” The author doesn’t make this mistake because he uses the word “discipline” consistently throughout his argument.

Summarize Argument

The author concludes that individuals who buy new cars today spend, on average, a larger amount relative to their incomes on a car than individuals spent 25 years ago. This is based on the fact that over the last 25 years, the average price paid for a new car has steadily increased in relation to the average individual income.

Notable Assumptions

The author assumes that the proportion of individuals who are buying cars today hasn’t significantly gone down. After all, if the proportion of individuals who buy cars has gone down, then it’s possible individuals still spend the same proportion of their income on cars; but other buyers (such as families or businesses) are paying a higher price and raising the average price of a car.

A

There has been a significant increase over the last 25 years in the proportion of individuals in households with more than one wage earner.

So, a higher proportion of households have more than one wage earner. But we’re talking about “individuals who buy new cars.” (A) doesn’t suggest that more households are buying a new car together.

B

The number of used cars sold annually is the same as it was 25 years ago.

The stimulus concerns changes in average price of a new car in relation to average income. The number of cars sold doesn’t affect average price of a car.

C

Allowing for inflation, average individual income has significantly declined over the last 25 years.

If income has gone down, that tends to support the position that individuals who buy new cars are spending a higher portion of their income than such individuals did 25 years ago.

D

During the last 25 years, annual new-car sales and the population have both increased, but new-car sales have increased by a greater percentage.

The stimulus concerns changes in average price of a new car in relation to average income. How many new cars are bought in relation to the population doesn’t affect the average price of a new car or how it relates to the average income.

E

Sales to individuals make up a smaller proportion of all new-car sales than they did 25 years ago.

This shows how the increase in average new car price can be explained by a greater portion of sales to non-individuals (such as a business). So, the increase in average price in relation to individual income doesn’t have to mean individuals are paying more for their cars.