A

Workers at nuclear power plants are required to receive extra training in safety precautions on their own time and at their own expense.

B

Workers at nuclear power plants are required to report to the manager any cases of accidental exposure to radiation.

C

The exposure of the workers to radiation at nuclear power plants was within levels the government considers safe.

D

Workers at nuclear power plants have filed only a few lawsuits against the management concerning unsafe working conditions.

E

Medical problems arising from work at a nuclear power plant are unusual in that they are not likely to appear until after an employee has left employment at the plant.

Joseph: My encyclopedia says that the mathematician Pierre de Fermat died in 1665 without leaving behind any written proof for a theorem that he claimed nonetheless to have proved. Probably this alleged theorem simply cannot be proved, since—as the article points out—no one else has been able to prove it. Therefore it is likely that Fermat was either lying or else mistaken when he made his claim.

Laura: Your encyclopedia is out of date. Recently someone has in fact proved Fermat’s theorem. And since the theorem is provable, your claim—that Fermat was lying or mistaken—clearly is wrong.

A

It purports to establish its conclusion by making a claim that, if true, would actually contradict that conclusion.

Laura’s premise doesn't support her conclusion well, but it doesn’t contradict her conclusion.

B

It mistakenly assumes that the quality of a person’s character can legitimately be taken to guarantee the accuracy of the claims that person has made.

Laura doesn’t make any claims or assumptions about the quality of Fermat’s character or how his character affects the accuracy of his claims.

C

It mistakes something that is necessary for its conclusion to follow for something that ensures that the conclusion follows.

In order for Laura’s conclusion— that Fermat was neither lying nor mistaken about proving the theorem— to follow, it is necessary that the theorem is actually provable. But the theorem being provable does not ensure that this conclusion follows.

D

It uses the term “provable” without defining it.

It’s true that Laura never defines the term “provable,” but this isn’t an error in her argument. She doesn’t need to define the term.

E

It fails to distinguish between a true claim that has mistakenly been believed to be false and a false claim that has mistakenly been believed to be true.

Laura doesn’t mention either of these kinds of claims, nor does she fail to distinguish between them. Joseph mistakenly believes a true claim— that the theorem is provable— to be false, but this doesn’t describe an error in Laura’s argument.

Critic: Most chorale preludes were written for the organ, and most great chorale preludes written for the organ were written by J. S. Bach. One of Bach’s chorale preludes dramatizes one hymn’s perspective on the year’s end. This prelude is agonizing and fixed on the passing of the old year, with its dashed hopes and lost opportunities. It does not necessarily reveal Bach’s own attitude toward the change of the year, but does reflect the tone of the hymn’s text. People often think that artists create in order to express their own feelings. Some artists do. Master artists never do, and Bach was a master artist.

Summary

Bach was a master artist. Master artists never create music to express their feelings, but other artists (i.e., some non-master artists) do. This can be diagrammed as follows:

Notable Valid Inferences

Bach never created music to express his feelings. This means the chorale prelude discussed in the stimulus was not made to reveal Bach’s attitudes toward the change of the year.

A

Bach believed that the close of the year was not a time for optimism and joyous celebration.

This could be true. The stimulus doesn’t offer information on how Bach felt about the year ending. While his prelude on this topic wasn’t celebratory, we know that Bach’s music wasn’t designed to express his feelings.

B

In composing music about a particular subject, Bach did not write the music in order to express his own attitude toward the subject.

This must be true. Bach was a master artist, which implies that he never created music to express his feelings.

C

In compositions other than chorale preludes, Bach wrote music in order to express his feelings toward various subjects.

This must be false. Master artists such as Bach never create music to express their feelings. If someone does create music to express their feelings, they must not be a master artist, and therefore must not be Bach, as shown in the diagram below.

D

Most of Bach’s chorale preludes were written for instruments other than the organ.

This could be true. While we know that most great chorale preludes written for the organ were composed by Bach, we don't have information about his preludes for other instruments. Bach's organ preludes may have been fewer in number compared to his preludes for other instruments.

E

Most of the great chorale preludes were written for instruments other than the organ.

This could be true. We know there are some great chorale preludes written specifically for the organ—we don’t know how these compare in number to the great chorale preludes for other instruments.

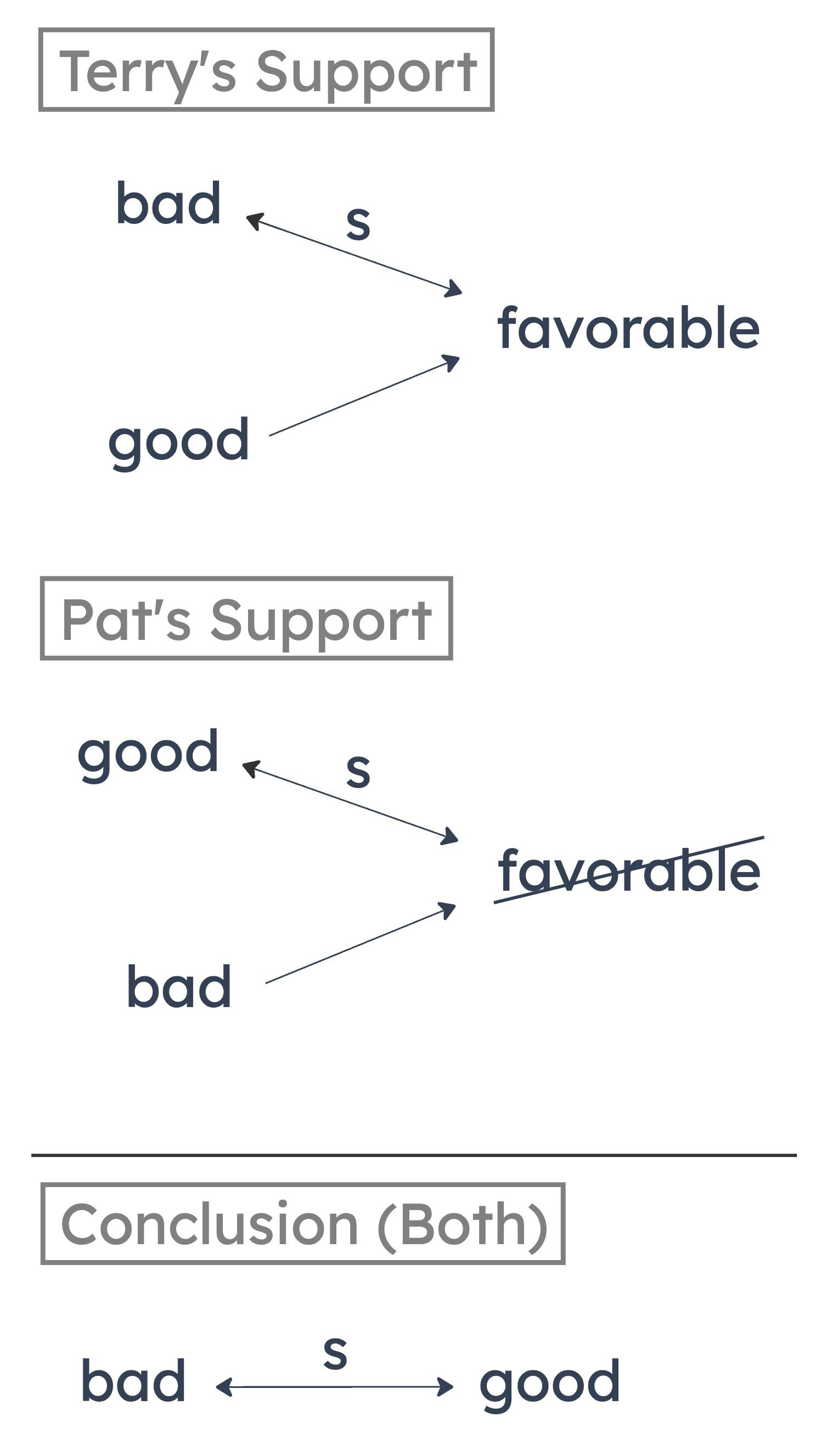

Pat: I agree with your conclusion, but not with the reasons you give for it. Some good actions actually do not have favorable consequences. But no actions considered to be bad by our society have favorable consequences, so your conclusion, that some actions our society considers bad are actually good, still holds.