Researcher: During the rainy season, bonobos (an ape species closely related to chimpanzees) frequently swallow whole the rough-surfaced leaves of the shrub Manniophyton fulvum. These leaves are likely ingested because of their medicinal properties, since ingestion of these leaves facilitates the elimination of gastrointestinal worms.

Summarize Argument: Phenomenon-Hypothesis

The researcher hypothesizes that bonobos eat Manniophyton fulvum leaves during the rainy season because they have medicinal properties. For evidence, he points to one such property: the leaves help eliminate gastrointestinal worms.

Notable Assumptions

The researcher assumes bonobos eat Manniophyton fulvum leaves because of their medicinal properties, and not for some other reason. This means assuming bonobos benefit from having fewer gastrointestinal worms and that the leaves are not worth eating just for their nutritional value.

A

Bonobos rarely swallow whole leaves of any plants other than M. fulvum.

This suggests there’s something unique about M. fulvum leaves—but not necessarily their medicinal value. It makes bonobos’ ingestion of these leaves more anomalous, but throws no weight behind the researcher’s particular hypothesis.

B

Chimpanzees have also been observed to swallow rough-surfaced leaves whole during the rainy season.

This is irrelevant. It doesn’t say chimpanzees eat M. fulvum leaves in particular, nor does it imply chimpanzees eat those leaves for their medicinal properties.

C

Of the rough-leaved plants available to bonobos, M. fulvum shrubs are the most common.

This doesn’t suggest bonobos eat them for their medicinal value. It’s equally compatible with the leading alternative hypotheses—for example, that bonobos eat the leaves for their nutritional value.

D

The leaves of M. fulvum are easier to swallow whole when they are wet.

This implies bonobos would prefer to eat M. fulvum leaves during the rainy season, rather than the dry season—but not why they choose to eat them in the first place. It doesn’t say the leaves have greater medicinal value when wet.

E

The rainy season is the time when bonobos are most likely to be infected with gastrointestinal worms.

This suggests M. fulvum leaves have more medicinal value to bonobos during the rainy season, since those leaves are more likely to rid them of worms. It makes it more likely the bonobos eat the leaves for their medicinal properties, as opposed to nutritional or other reasons.

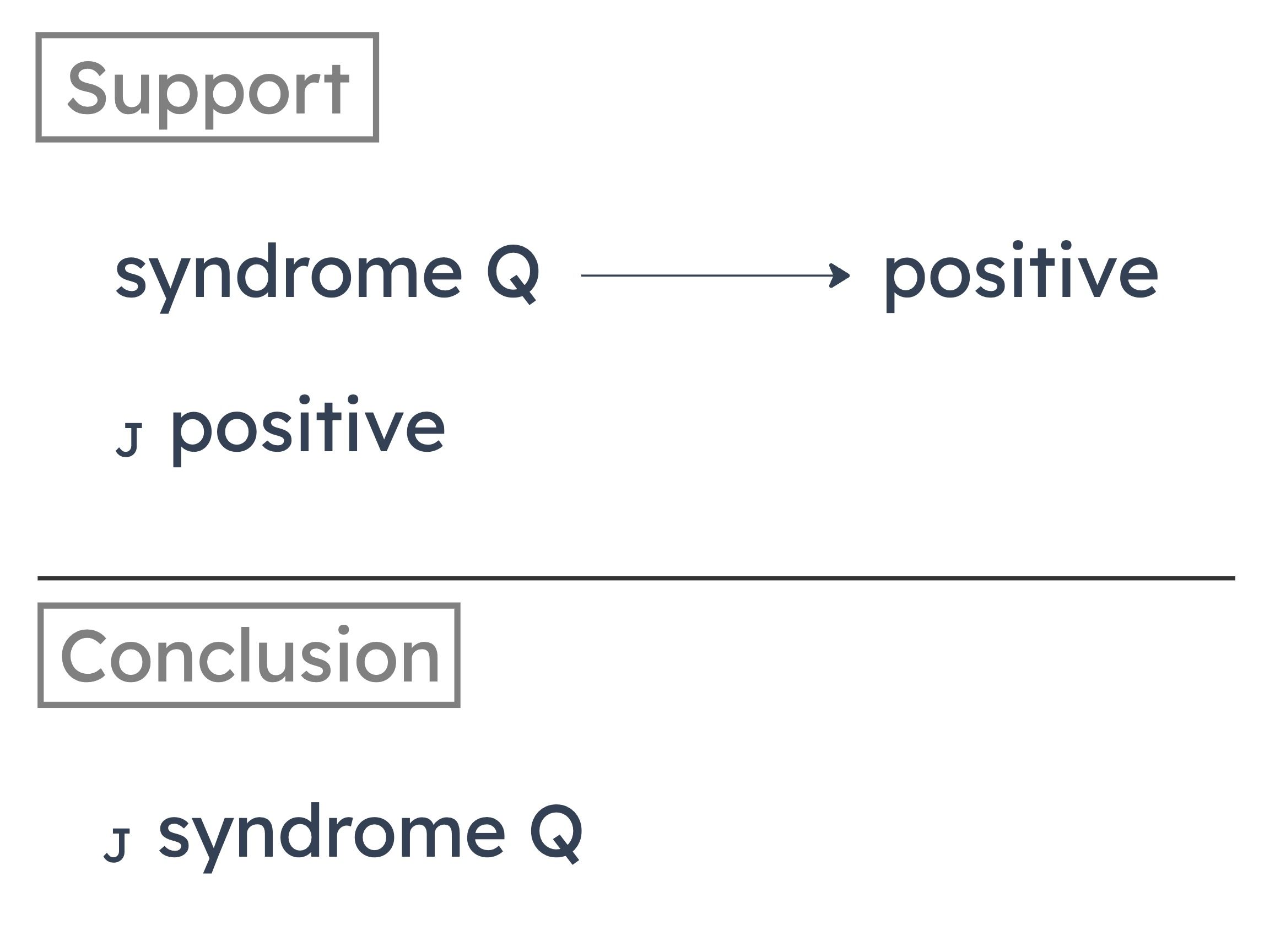

In other words, just because Justine tested positive doesn’t necessarily mean that she has syndrome Q. She might just have had a false positive test.

A

It confuses the claim that a subject will test positive when the syndrome is present with the claim that any subject who tests positive has the syndrome.

B

It makes a general claim regarding the accuracy of the test for syndrome Q without providing adequate scientific justification for that claim.

C

It fails to adequately distinguish between a person’s not having syndrome Q and that person’s not testing positive for syndrome Q.

D

It confuses a claim about the accuracy of a test for syndrome Q in an arbitrary group of individuals with a similar claim about the accuracy of the test for a single individual.

E

It confuses the test’s having no reliable results for the presence of syndrome Q with its having no reliable results for the absence of syndrome Q.

A

People with a high-fat diet who engage in regular, vigorous physical activity are much less likely to develop heart disease than are sedentary people with a low-fat diet.

B

Triglyceride levels above 2 milligrams per milliliter increase the risk of some serious illnesses not related to heart disease.

C

Shortly after a person ceases to regularly consume alcohol and processed sugar, that person’s triglyceride levels drop dramatically.

D

Heart disease interferes with the body’s ability to metabolize triglycerides.

E

People who maintain strict regimens for their health tend to adopt low-fat diets and to avoid alcohol and processed sugar.