Summarize Argument

The author concludes that children have a good grasp on what’s real versus what’s pretend. For one thing, they can demonstrate their understanding if asked directly. For another, their make-believe games rely on being able to tell real and pretend apart.

Identify Conclusion

The conclusion is about how children think: “Children clearly have a reasonably sophisticated understanding of what is real and what is pretend.”

A

Children apparently have a reasonably sophisticated understanding of what is real and what is pretend.

Make-believe wouldn’t work without a good grasp on what’s real and what’s pretend, and children can tell the two apart if asked. Thus, children have a sophisticated understanding of what’s real and what’s pretend.

B

Children who have acquired a command of language generally answer correctly when asked about whether a thing is real or pretend.

This is a premise that supports the author’s argument. If children can answer correctly whether something is real or not, they clearly have a good understanding of real versus pretend.

C

Even a very young child can tell the difference between a lion and someone pretending to be a lion.

This is an example of children doing make-believe. Since they’re able to tell the difference between a pretend, fun lion and a real, terrifying lion, they must have a good grasp on what’s real and what’s pretend.

D

Children would be terrified if they believed they were in the presence of a real lion.

This supports the conclusion. Since children aren’t terrified in the presence of a pretend lion, they must know it isn’t real. Therefore, they have a good grasp on real versus pretend.

E

The pleasure children get from make-believe would be impossible to explain if they could not distinguish between what is real and what is pretend.

This premise supports the author’s conclusion. Since children are able to get pleasure from make believe, they must know what’s real and what’s pretend.

Summary

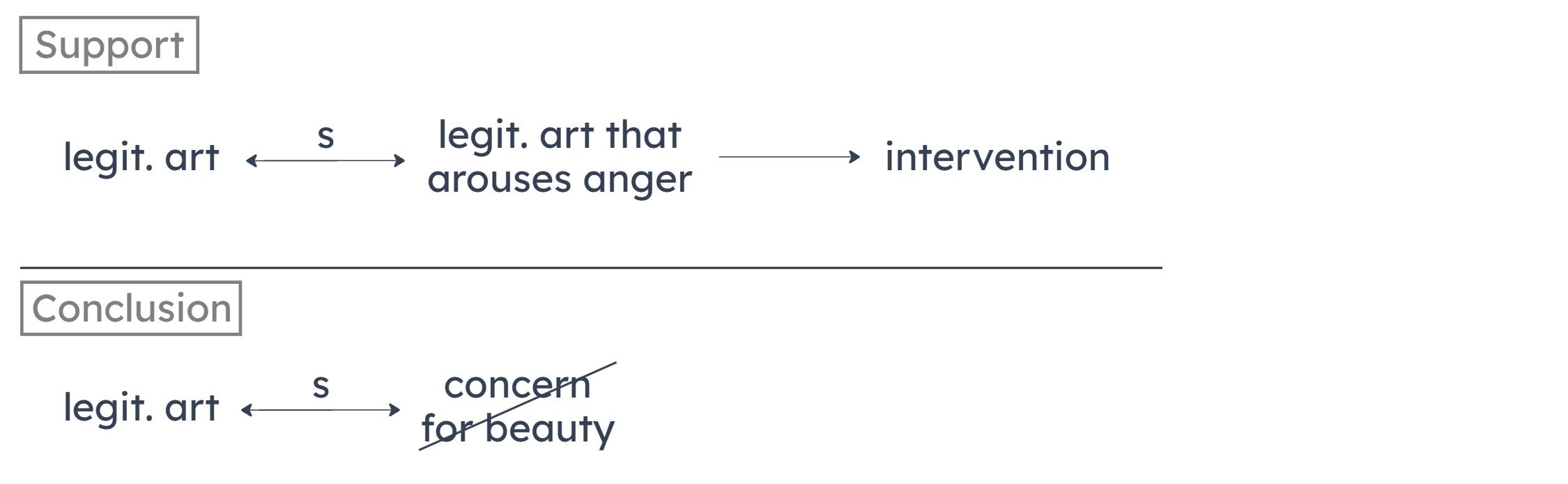

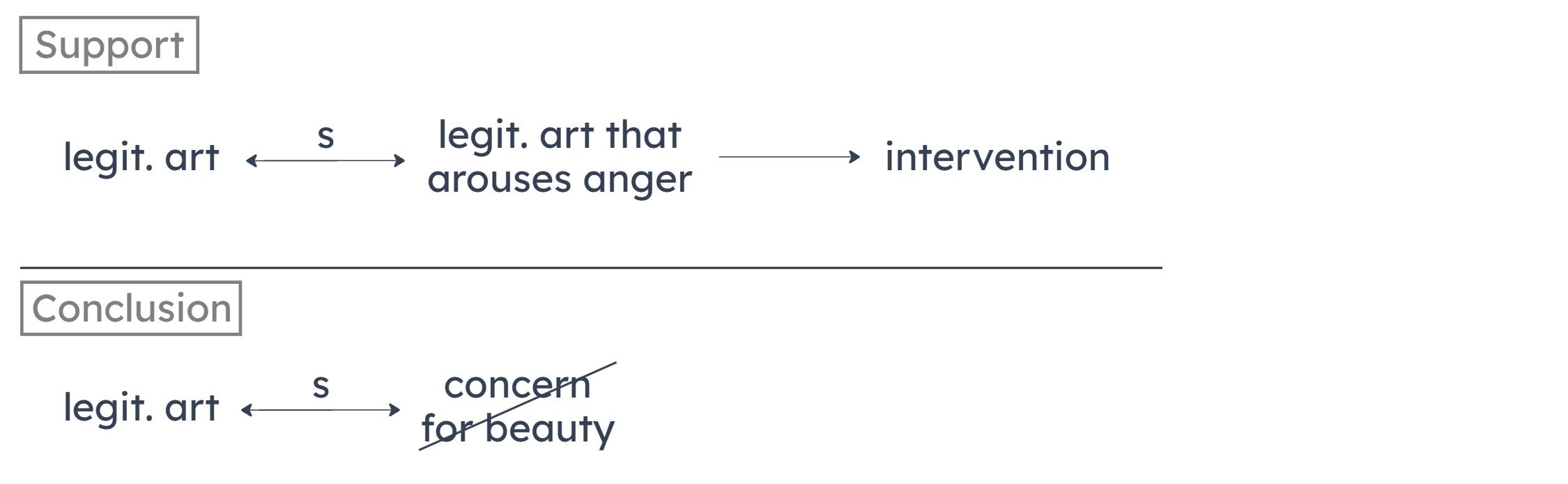

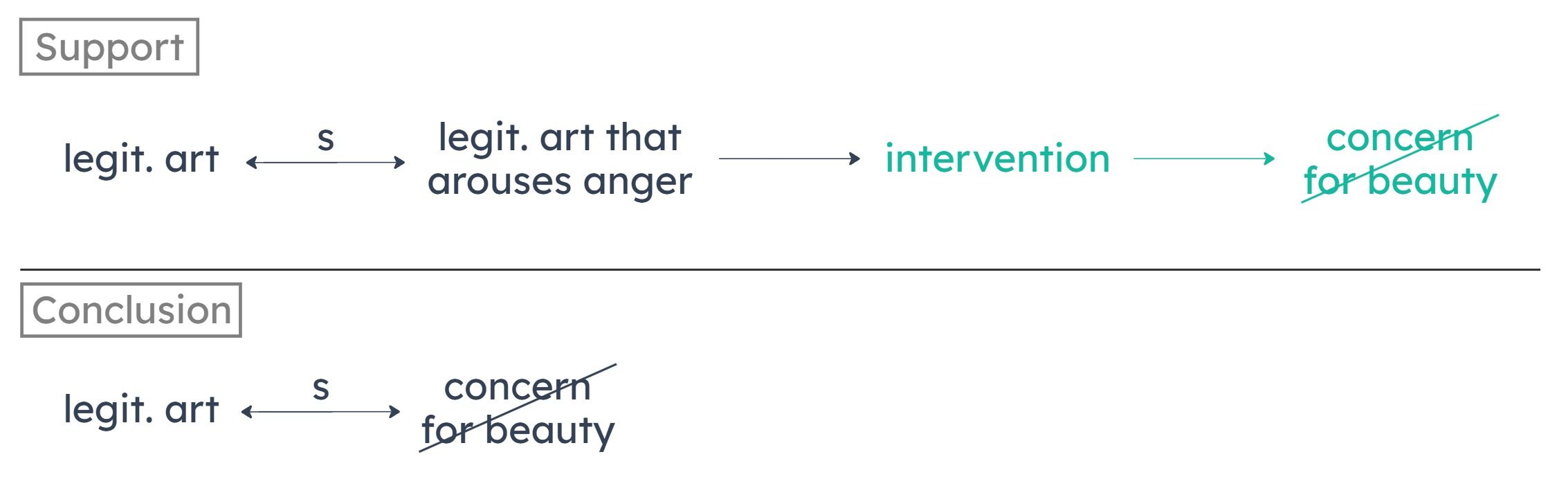

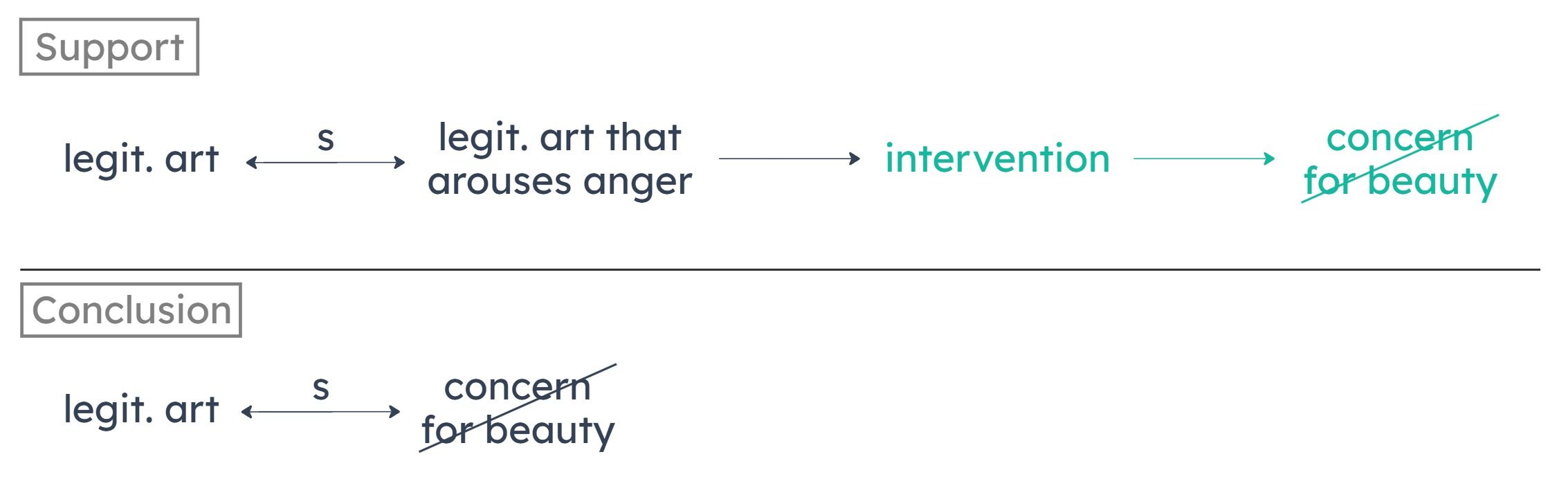

The author concludes that some legitimate art is not concerned with beauty. Why? Because of the following:

Some legitimate art aims to arouse anger.

All legitimate art with the aim of arousing anger intentionally calls for concrete intervention.

Some legitimate art aims to arouse anger.

All legitimate art with the aim of arousing anger intentionally calls for concrete intervention.

Missing Connection

The conclusion asserts that some legitimate art isn’t concerned with beauty. But the premises don’t tell us anything about what’s not concerned with beauty. So, at a minimum, we know that the correct answer should allow us to establish that something is not concerned with beauty.

To go further, we can anticipate some specific relationships that could get us from the premise to the concept “not concerned with beauty.” We know from the premises that some legitimate art aims to arouse anger. We also know that some legitimate art calls for concrete intervention. Either of these could make the argument valid:

Any art that aims to arouse anger is not concerned with beauty.

Any art that calls for concrete intervention is not concerned with beauty.

To go further, we can anticipate some specific relationships that could get us from the premise to the concept “not concerned with beauty.” We know from the premises that some legitimate art aims to arouse anger. We also know that some legitimate art calls for concrete intervention. Either of these could make the argument valid:

Any art that aims to arouse anger is not concerned with beauty.

Any art that calls for concrete intervention is not concerned with beauty.

A

There are works that are concerned with beauty but that are not legitimate works of art.

(A) tells us that there are some works concerned with beauty that aren’t legitimate art. But we’re trying to prove that there are some legitimate artworks that are NOT concerned with beauty. Learning about works that ARE concerned with beauty doesn’t help us prove that certain works are NOT concerned with beauty.

B

Only those works that are exclusively concerned with beauty are legitimate works of art.

(B) asserts that in order to be legitimate, a work must be exclusively concerned with beauty. But we’re trying to prove that there are legitimate works that are NOT concerned with beauty. (B) contradicts our conclusion.

C

Works of art that call for intervention have a merely secondary concern with beauty.

(C) establishes that art that calls for intervention has a “secondary” concern with beauty. But we want to establish that some of these works are NOT concerned with beauty. Having a secondary concern with beauty does not imply NO concern with beauty.

D

No works of art that call for intervention are concerned with beauty.

(D) asserts that if a work of art calls for intervention, then it’s not concerned with beauty. Since we know some legitimate art calls for intervention, (D) allows us to conclude that some legitimate art is not concerned with beauty.

E

Only works that call for intervention are legitimate works of art.

(E) doesn’t establish what kind of art is not concerned with beauty. Since neither this answer nor the premises tell us what kind of art is not concerned with beauty, there’s no way (E) can make the argument valid.

Summarize Argument

The scientist concludes the first dinosaurs to fly probably glided out of trees, rather than flying from a running start. Why? Because gliding from trees requires only simple wings that are stepping stones, evolutionarily, to the larger wings of later dinosaurs.

Notable Assumptions

The scientist assumes it’s more likely the first flighted dinosaurs had wings for gliding than wings for lifting off. This means assuming wings for lifting off the ground are either less simple than wings for gliding or less of a stepping stone toward the wings of later dinosaurs. It also means assuming there’s no other characteristic of the first flighted dinosaurs that would make it less likely they glided from trees than lifted off the ground.

A

Early flying dinosaurs built their nests at the base of trees.

This doesn’t favor the scientist’s argument. It implies the first flighted dinosaurs lived on the ground, which if anything makes it less likely they flew by gliding out of trees.

B

Early flying dinosaurs had sharp claws and long toes suitable for climbing.

This strengthens the scientist’s argument. It implies the first flighted dinosaurs were capable of climbing trees, which rules out the possibility they were confined to the ground.

C

Early flying dinosaurs had unusual feathers that provided lift while gliding, but little control when taking flight.

This strengthens the scientist’s argument. It implies the first flighted dinosaurs had biological characteristics more consistent with gliding than with lifting off from the ground.

D

Early flying dinosaurs had feathers on their toes that would have interfered with their ability to run.

This strengthens the scientist’s argument. It implies the first flighted dinosaurs had toes that would have made it difficult to lift off from a running start.

E

Early flying dinosaurs lived at a time when their most dangerous predators could not climb trees.

This strengthens the scientist’s argument. It implies the first flighted dinosaurs had a reason to climb trees: to avoid predators. It rules out the possibility those dinosaurs would have gained no advantage by living in trees.

Summarize Argument

The author concludes that any impact from viewers’ perception that political candidates who blink excessively during a debate perform less well than those who blink an average amount is harmful. This is because a candidate’s rate of blinking is not a feature that contributes to performing well in elected office.

Notable Assumptions

The author assumes that blink rate is not a signal of features that are relevant to performing well in office, such as confidence.

A

Voters’ judgments about candidates’ debate performances rarely affect the results of national elections.

The argument never specifies that it’s concerned only with national elections. Effects on state elections or local elections can still be harmful. Also, the conclusion doesn’t assert that there are any effects on elections. Only that if there are effects, they’re harmful.

B

Blinking too infrequently during televised debates has the same effect on viewers’ judgments of candidates as blinking excessively.

This simply describes another way that blink rate can affect someone’s perception of a candidate. This doesn’t undermine the author’s position that perceptions based on blink rate are harmful.

C

Excessive blinking has been shown to be a mostly reliable indicator of a lack of confidence.

This suggests that excessive blink rate can be a signal of confidence, which is a feature that contributes to performance in elected office. So, judging a candidate based on excessive blinking might not be harmful, because it’s an indicator of something we were told is relevant.

D

Candidates for top political offices who are knowledgeable also tend to be confident.

This doesn’t tell us anything about blink rate or why judging candidates based on blink rate might not be harmful.

E

Viewers’ judgments about candidates’ debate performances are generally not affected by how knowledgeable the candidates appear to be.

This doesn’t tell us anything about blink rate or why judging candidates based on blink rate might not be harmful.