"Surprising" Phenomenon

There are higher default rates among mortgage borrowers with the highest credit scores than there are among other mortgage borrowers, even though higher credit scores typically correspond to lower risks of loan default.

Objective

The right answer will explain a key difference between mortgage borrowers with the highest credit scores and other borrowers. That difference must shed light on some factor that explains why the former group tend to have a harder time repaying their loans.

A

Mortgage lenders are much less likely to consider risk factors other than credit score when evaluating borrowers with the highest credit scores.

This is what we’re looking for! Mortgage lenders are much less likely to take the time to comprehensively evaluate borrowers with the highest credit scores, so they end up loaning to riskier people whose red flags would have disqualified them if the lender had looked closer.

B

Credit scores reported to mortgage lenders are based on collections of data that sometimes include errors or omit relevant information.

This doesn’t describe any difference between the highest-credit-score borrowers and the others. Because these inaccuracies presumably occur across the board, “B” doesn’t explain why a correlation that holds for most borrowers falls apart for those with the highest credit scores.

C

A potential borrower’s credit score is based in part on the potential borrower’s past history in paying off debts in full and on time.

Of course this is true! These factors play a huge role in a person’s credit score. But that’s true for every person at every credit score level, so nothing here explains why a correlation that holds for most borrowers falls apart for those with the highest credit scores.

D

For most consumers, a mortgage is a much larger loan than any other loan the consumer obtains.

Of course this is true! Houses are expensive. But this doesn’t point to a difference between highest-credit-score consumers and others, so nothing here explains why a correlation that holds for most borrowers falls apart for those with the highest credit scores.

E

Most potential borrowers have credit scores that are neither very low nor very high.

This seems quite plausible, but it doesn’t help us understand what’s happening for mortgage borrowers with the highest credit scores that’s different from what’s happening for other borrowers.

Summary

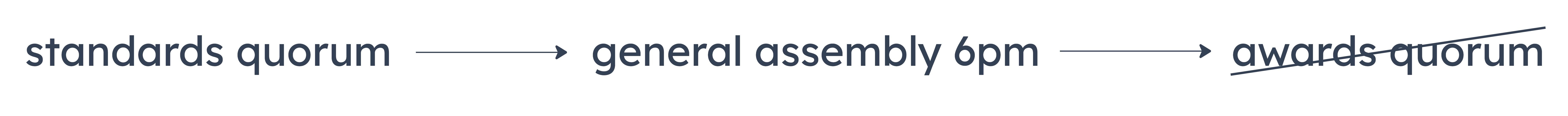

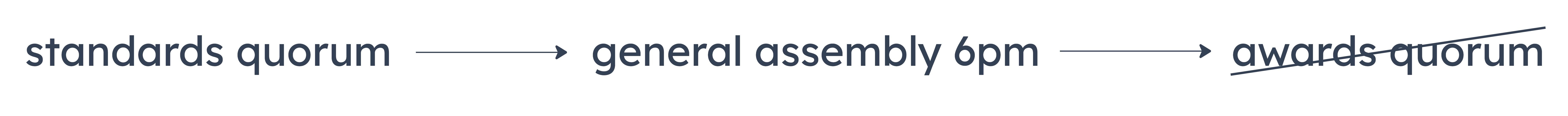

The stimulus can be diagrammed as follows:

Notable Valid Inferences

The standards committee and the awards committee cannot both have a quorum.

A

If the general assembly does not begin at 6:00 P.M. today, then the awards committee has a quorum.

This could be false. If the general assembly does not begin at 6:00 PM, we know that the standards committee doesn’t have a quorum, but it could be the case that the awards committee doesn’t have a quorum either.

B

If the standards committee does not have a quorum, then the awards committee has a quorum.

This could be false. It is possible for neither committee to have a quorum.

C

If the general assembly begins at 6:00 P.M. today, then the standards committee has a quorum.

This could be false. We know that if the standards committee has a quorum, then the general assembly will begin at 6:00 PM. (C) reverses the sufficient and necessary conditions.

D

If the general assembly does not begin at 7:00 P.M. today, then the standards committee has a quorum.

This could be false. If the general assembly does not begin at 7:00 PM, we know that the awards committee doesn’t have a quorum, but it could be the case that the standards committee doesn’t have a quorum either.

E

If the standards committee has a quorum, then the awards committee does not have a quorum.

This must be true. As shown below, by chaining the conditional claims, we see that if the standards committee has a quorum, then the awards committee does not have a quorum.

Galindo: I disagree. An oil industry background is no guarantee of success. Look no further than Pod Oil’s last chief executive, who had decades of oil industry experience but steered the company to the brink of bankruptcy.

Summarize Argument: Counter-Position

Galindo argues that Simpson’s lack of experience in the oil industry doesn’t disqualify him as a chief executive candidate. He offers two premises:

(1) Having a background in the oil industry doesn’t guarantee success.

(2) The last chief executive was unsuccessful despite their background in the oil industry.

(1) Having a background in the oil industry doesn’t guarantee success.

(2) The last chief executive was unsuccessful despite their background in the oil industry.

Identify and Describe Flaw

This is the flaw of mistaking sufficiency for necessity. Fremont argues that having oil industry experience is a necessary condition for being a successful chief executive. Instead of arguing against this claim, Galindo argues that having an oil industry background isn’t a sufficient condition for a chief executive to be successful. Fremont never claimed that an oil background was sufficient, though—he just said it was necessary. Galindo doesn’t address Fremont’s actual argument, so his disagreement with Fremont is unsupported.

A

fails to justify its presumption that Fremont’s objection is based on personal bias

Galindo does not presume that Fremont’s objection is based on personal bias, so no such justification would be necessary.

B

fails to distinguish between relevant experience and irrelevant experience

It isn’t necessary for Galindo to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant experience, because both Fremont and Galindo limit their arguments to discussions of relevant experience (a background in the oil industry).

C

rests on a confusion between whether an attribute is necessary for success and whether that attribute is sufficient for success

This is the cookie-cutter flaw in Galindo’s argument. Fremont argues that an oil industry background is necessary for success; Galindo counters that such a background is not sufficient to ensure success. Galindo mistakes Fremont’s necessary condition for a sufficient condition.

D

bases a conclusion that an attribute is always irrelevant to success on evidence that it is sometimes irrelevant to success

Galindo does not conclude that an oil industry background is always irrelevant to success. He states that such a background does not necessarily guarantee success, but he doesn’t suggest that oil industry experience is always irrelevant to success.

E

presents only one instance of a phenomenon as the basis for a broad generalization about that phenomenon

Galindo’s example successfully proves that an oil industry background doesn’t guarantee success, so the efficacy of his example or the fact that he only offers one isn’t a flaw. Rather, the flaw is that the claim his example proves does not actually respond to Fremont’s argument.

Summarize Argument: Phenomenon-Hypothesis

The legislator hypothesizes that voters don’t like the highway bill. She bases this on a correlation: the majority party both supported the bill’s passage and is predicted to lose more than a dozen seats in the upcoming election.

Identify and Describe Flaw

This is a “correlation doesn’t imply causation” flaw, where the legislator sees a correlation and concludes that one thing causes the other without ruling out alternative hypotheses. Specifically, she overlooks two key alternatives:

(1) The causal relationship could be reversed—maybe the majority party’s unpopularity caused them to support the highway bill. Maybe the party supported the popular highway bill as a result of their poor poll performance!

(2) Some other factor could be causing the correlation—maybe the majority party is unpopular for other reasons and they also happen to support the highway bill!

(1) The causal relationship could be reversed—maybe the majority party’s unpopularity caused them to support the highway bill. Maybe the party supported the popular highway bill as a result of their poor poll performance!

(2) Some other factor could be causing the correlation—maybe the majority party is unpopular for other reasons and they also happen to support the highway bill!

A

gives no reason to think that the predicted election outcome would be different if the majority party had not supported the bill

This describes the legislator’s cookie-cutter “correlation proves causation” error. The legislator fails to establish that the majority party’s support of the bill is what caused the predicted election outcome. What if the party is unpopular for entirely unrelated reasons?

B

focuses on the popularity of the bill to the exclusion of its merit

The bill’s merit is not relevant to the legislator’s argument. She is focused on the bill’s popularity, not its actual content.

C

infers that the bill is unpopular from a claim that presupposes its unpopularity

The legislator does not presuppose the bill’s unpopularity; rather, she attempts to demonstrate it by introducing the information that a party that supported the bill is itself unpopular. (C) describes a “circular reasoning” flaw, which is not the error the legislator commits.

D

takes for granted that the bill is unpopular just because the legislator wishes it to be unpopular

The legislator gives no indication that she wishes the bill to be unpopular. For all we know, she could be a member of the majority party and a supporter of the bill!

E

bases its conclusion on the views of voters without establishing their relevant expertise on the issues involved

The legislator’s conclusion is entirely about voters’ views, regardless of the merits of these views or the voters’ qualifications to hold them. Her argument doesn’t rely at all on establishing the voters’ relevant expertise, so it doesn’t matter that she does not do this.