Columnist: Research shows significant reductions in the number of people smoking, and especially in the number of first-time smokers in those countries that have imposed stringent restrictions on tobacco advertising. This provides substantial grounds for disputing tobacco companies’ claims that advertising has no significant causal impact on the tendency to smoke.

Summarize Argument

The columnist concludes that, contrary to what tobacco companies claim, advertising indeed has an effect on smoking habits. As evidence, she cites research showing that countries with the strictest tobacco advertising laws also have the greatest reduction in the number of people who smoke.

Notable Assumptions

Based on a correlation between tobacco advertising laws and smoking rates, the author assumes that the former causes the latter. This means the author doesn’t believe the relationship is the inverse (i.e. decreasing rates of smoking cause stringent tobacco advertising laws), or that some third factor (i.e. health campaigns, social attitudes) aren’t responsible for both strict tobacco advertising laws and declining smoking rates.

A

People who smoke are unlikely to quit merely because they are no longer exposed to tobacco advertising.

While the author indeed claims that countries with stringent advertising laws see a decline in smoking, she specifies that decline is most prominent among first-time smokers. Even if current smokers didn’t quit due to the laws, would-be smokers were deterred.

B

Broadcast media tend to have stricter restrictions on tobacco advertising than do print media.

We don’t care which sort of media is strictest. We’re trying to weaken the causal relationship between advertising laws and smoking rates.

C

Restrictions on tobacco advertising are imposed only in countries where a negative attitude toward tobacco use is already widespread and increasing.

This adds a third factor that isn’t smoking rates or advertising laws. Negative attitudes towards tobacco use cause a decline in smoking and strict tobacco laws.

D

Most people who begin smoking during adolescence continue to smoke throughout their lives.

Like (A), this tells us many people don’t quit. That’s fine—the laws still have an effect on first-time smokers, as well as perhaps some long-time ones.

E

People who are largely unaffected by tobacco advertising tend to be unaffected by other kinds of advertising as well.

We have no idea what percentage of people are unaffected by tobacco advertising. This could weaken if most people were unaffected by tobacco advertising, but we don’t have that information.

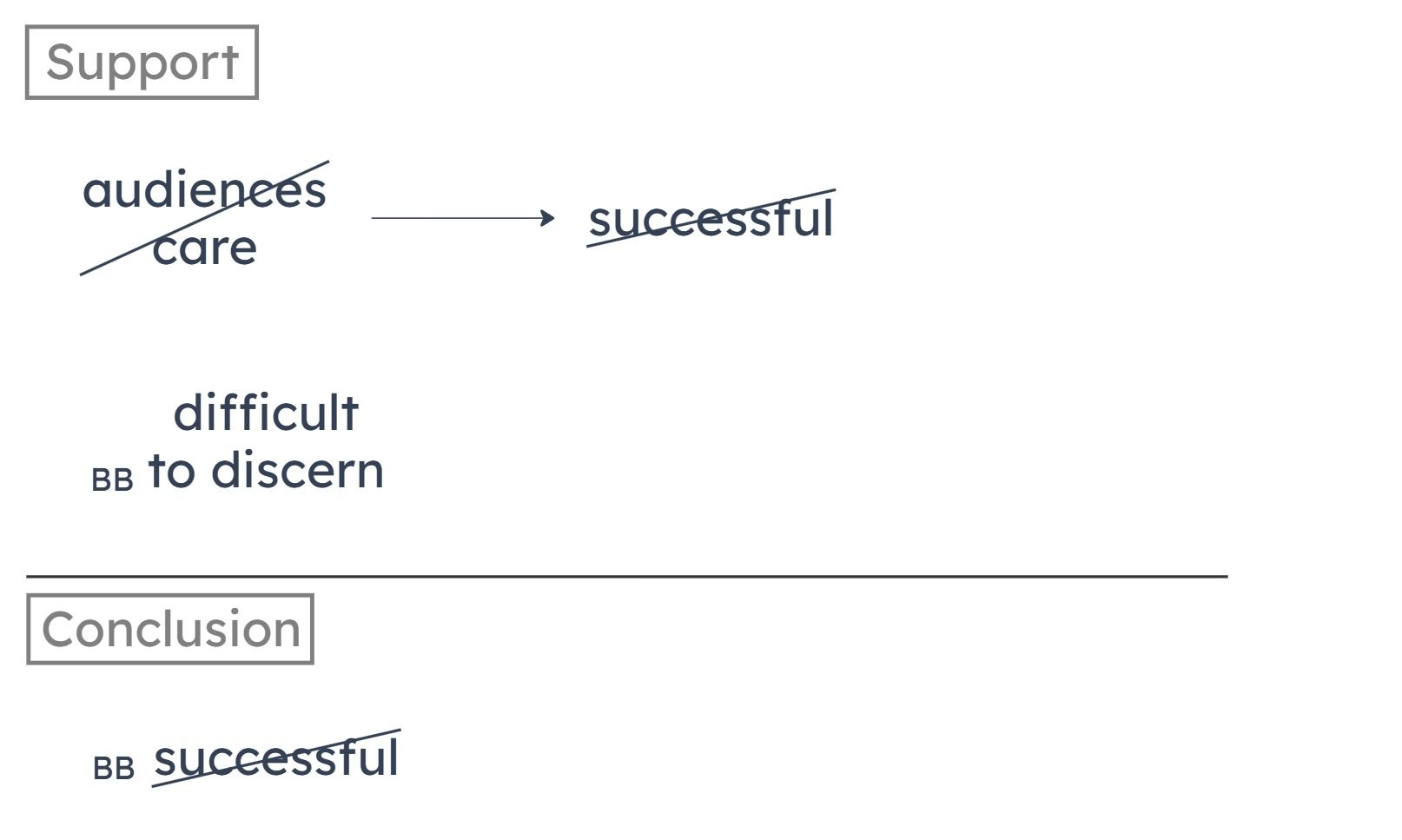

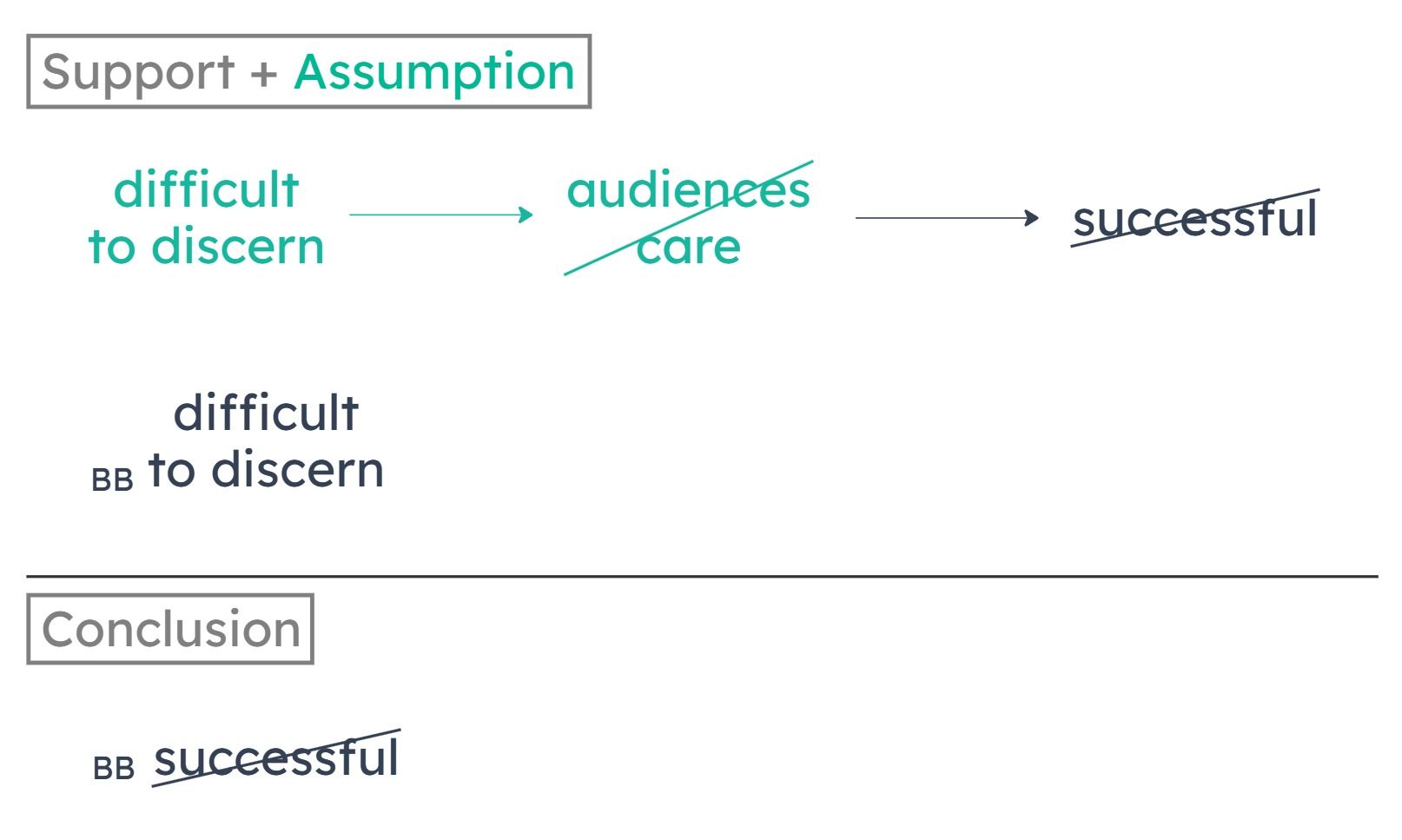

In Brecht’s plays, the audiences and actors find it difficult to discern any of the characters’ personalities.

In order to be a successful drama, audiences must care what happens to at least some of the characters.

The other premise tells us that audiences/actors find it difficult to discern characters’ personalities in Brecht’s plays. If we can show that this difficulty in discerning characters’ personalities implies that audiences won’t care about the characters, that would provide the missing link.

A

An audience that cannot readily discern a character’s personality will not take any interest in that character.

B

A character’s personality is determined primarily by the motives and beliefs of that character.

C

The extent to which a play succeeds as a drama is directly proportional to the extent to which the play’s audiences care about its characters.

D

If the personalities of a play’s characters are not readily discernible by the actors playing the roles, then those personalities are not readily discernible by the play’s audience.

E

All plays that, unlike Brecht’s plays, have characters with whom audiences empathize succeed as dramas.

Jeneta: Increasingly, I’ve noticed that when a salesperson thanks a customer for making a purchase, the customer also says “Thank you” instead of saying “You’re welcome.” I’ve even started doing that myself. But when a friend thanks a friend for a favor, the response is always “You’re welcome.”

"Surprising" Phenomenon

Why do we say “You’re welcome” when a friend thanks us for doing him a favor, but when a salesperson thanks a customer for buying something, the customer also says, “Thank you,” instead of “You’re welcome”?

Objective

The correct answer should tell us about a difference between the salesperson-customer context and the friend-friend context that could explain why a customer says “Thank you” whereas a friend says “You’re welcome.”

A

Customers regard themselves as doing salespeople a favor by buying from them as opposed to someone else.

This would lead us to expect customers to say “You’re welcome.”

B

Salespeople are often instructed by their employers to thank customers, whereas customers are free to say what they want.

Even if customers are free to say whatever they want, why do they say “Thank you” instead of “You’re welcome”? This answer doesn’t provide a theory.

C

Salespeople do not regard customers who buy from them as doing them a favor.

This relates to the salesperson’s motivations for she says. But it doesn’t tell us about the customer’s.

D

The way that people respond to being thanked is generally determined by habit rather than by conscious decision.

We have no reason to think that customers would develop a habit of saying “Thank you” instead of “You’re welcome.” This doesn’t provide a theory for how customers began to say “Thank you” to salespeople.

E

In a commercial transaction, as opposed to a favor, the customer feels that the benefits are mutual.

In the salesperson-customer context (commercial transaction), the customer feels benefited, which is why they say “Thank you.” In the friend-friend favor context, the person who does the favor doesn’t necessarily feel mutual benefit. This is why he says “You’re welcome.”

Some video game makers have sold the movie rights for popular games. However, this move is rarely good from a business perspective. After all, StarQuanta sold the movie rights to its popular game Nostroma, but the poorly made film adaptation of the game was hated by critics and the public alike. Subsequent versions of the Nostroma video game, although better than the original, sold poorly.

Summarize Argument

The author concludes that selling the movie rights for popular video games is rarely good for business. He supports this by noting that the film adaptation of Nostroma was hated by critics and audiences, and later versions of the game sold poorly, even though they were better than the original.

Identify and Describe Flaw

This is the cookie-cutter flaw of hasty generalization, where the author draws a broad conclusion based on too little evidence. Here, the author argues that selling the movie rights for video games is usually bad for business, but he only provides one example. Perhaps Nostroma doesn’t accurately reflect most video game movies. Maybe it was just a bad movie, and most video game movies are successful and boost sales.

A

draws a general conclusion on the basis of just one individual case

The author draws a general conclusion about selling the movie rights for video games on the basis of just one individual case: the Nostroma movie. But the Nostroma movie might not accurately reflect the business impact of most video game movie deals.

B

infers that a product will be disliked by the public merely from the claim that the product was disliked by critics

The author explicitly states that the Nostroma movie was hated by both critics and the public. He doesn’t assume that the public will dislike something just because critics disliked it.

C

restates as a conclusion a claim earlier presented as evidence for that conclusion

This is the cookie-cutter flaw of circular reasoning, where the argument’s conclusion merely restates one of its premises. The author doesn’t make this mistake. He draws his conclusion based on an example that is distinct from that conclusion.

D

takes for granted that products with similar content that are in different media will be of roughly equal popularity

The author doesn't assume that games and movies about similar content will be equally popular. If anything, he assumes that the movie version of a popular video game will be significantly less popular.

E

treats a requirement for a product to be popular as something that ensures that a product will be popular

This is the cookie-cutter flaw of confusing necessary and sufficient conditions. The author doesn’t make this mistake. In fact, he never presents a necessary condition for a product to be popular in the first place.