"Surprising" Phenomenon

High-stress points make a bridge likely to fracture, but aren’t the sites of fractures themselves.

Objective

The right answer will be a hypothesis that explains why stress points don’t themselves fracture, despite stress points contributing to fractures. The explanation must also explain why stress points are especially unlikely places for fractures, given that the stimulus tells us fractures generally don’t occur on those points.

A

In many structures other than bridges, such as ship hulls and airplane bodies, fractures do not develop at high-stress points.

This backs up the stimulus, but it doesn’t explain why high-stress points don’t fracture despite making fractures more likely.

B

Fractures do not develop at high-stress points, because bridges are reinforced at those points; however, stress is transferred to other points on the bridge where it causes fractures.

This explains the mechanism behind fractures. High-stress points are reinforced against fractures, but transfer stress to weaker points where fractures occur. We now know why high-stress points contribute to fractures without themselves fracturing.

C

In many structures, the process of fracturing often causes high-stress points to develop.

High-stress points make fractures more likely. We don’t care what happens after a fracture.

D

Structures with no high-stress points can nonetheless have a high probability of fracturing.

This doesn’t matter. We’re concerned with bridges that do have high-stress points.

E

Improper bridge construction, e.g., low-quality welding or the use of inferior steel, often leads both to the development of high-stress points and to an increased probability of fracturing.

This doesn’t explain why high-stress points themselves aren’t the site of fractures, despite high-stress points making fracturing more likely. It doesn’t explain the surprise in the stimulus.

Summarize Argument: Counter-Position

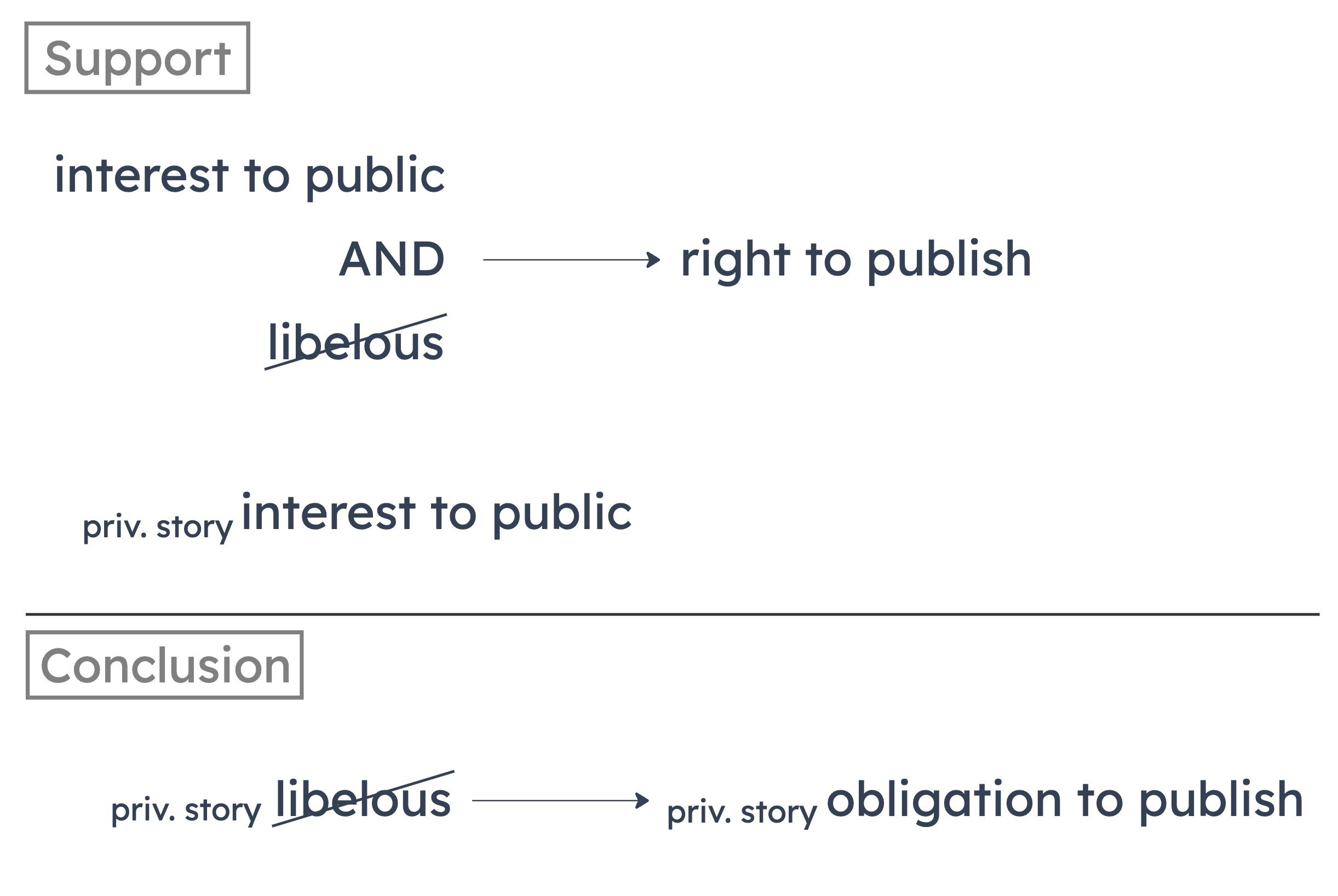

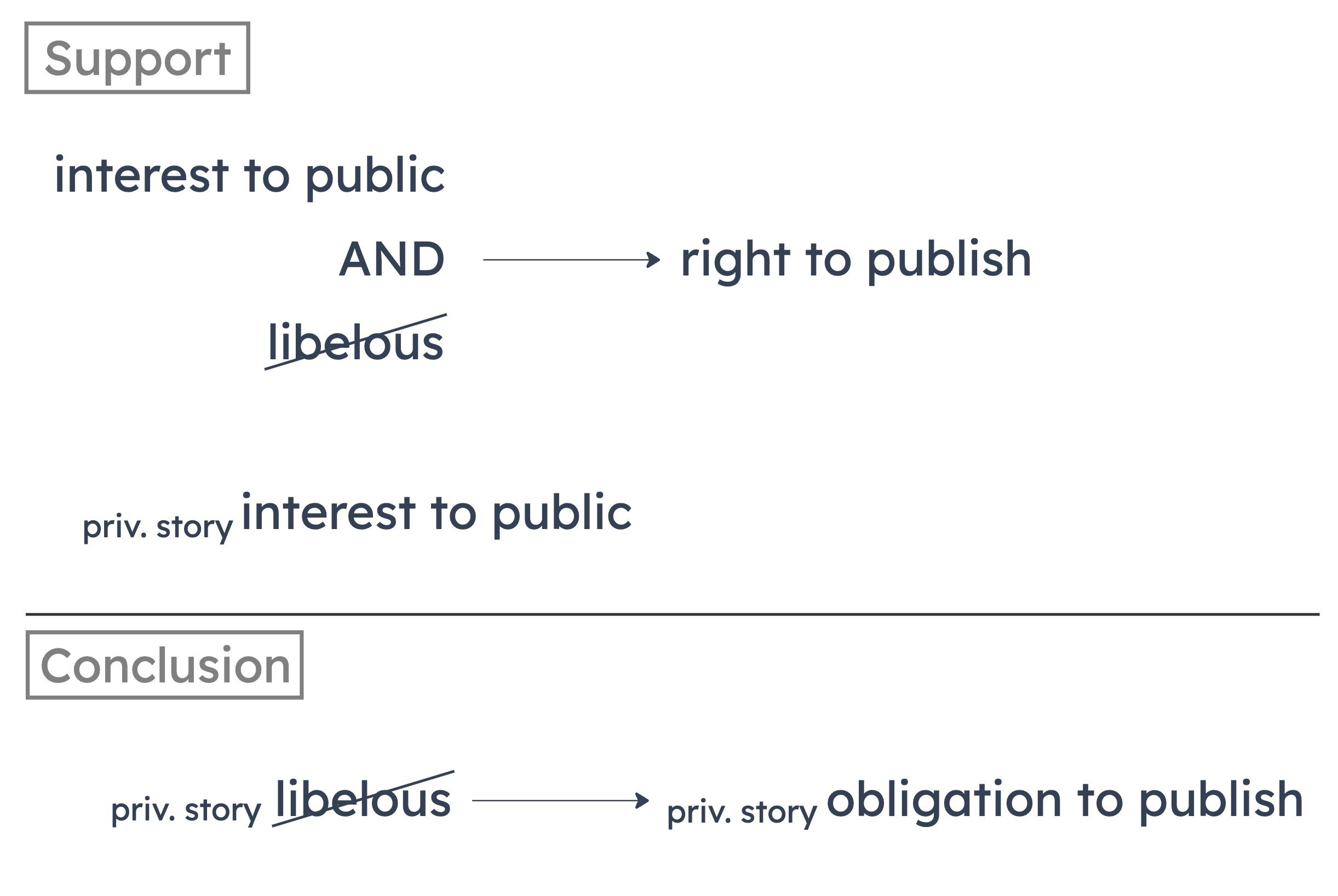

The stimulus can be diagrammed as follows:

Identify and Describe Flaw

The argument presumes, based on the fact that the press has a right to do something, that the press has an obligation to do that thing. The argument gives two sufficient for having the right to publish a story (that the story isn’t libelous and that the story is of interest to the public). When these two sufficient conditions are met, all we can say is that the press has a right to publish a story––the premises don’t say anything about what the press is obligated to do.

A

the press can publish nonlibelous stories about private individuals without prying into their personal lives

The argument doesn’t discuss whether or not the press is prying into people’s personal lives. In the context of the argument, we see that many people say that the press shouldn’t pry, but the author’s argument itself doesn’t discuss whether or not the press can (or should) pry.

B

one’s having a right to do something entails one’s having an obligation to do it

This is what the author presumes. The argument lays out the sufficient conditions for when the press has the right to publish stories; we don’t have the conditions to determine what the press is obligated to do. The obligation of the press is an assumption made by the author.

C

the publishing of information about the personal lives of private individuals cannot be libelous

The argument does not make this presumption. The argument gives a conditional conclusion for when stories about private individuals are not libelous––the author isn’t presuming that these stories cannot be libelous; he’s just only talking about the stories that aren’t libelous.

D

if one has an obligation to do something then one has a right to do it

This is a reversal of the assumption that the author does make. The author presumes that, if one has the right to do something, then one has the obligation to do it. (D) reverses the sufficient and necessary conditions of that relationship.

E

the press’s right to publish always outweighs the individual’s right not to be libeled

The author’s conclusion applies to stories that aren’t libelous––according to the author, the press has the obligation to publish when stories aren’t libelous (and are of interest to the public). If a story is libelous, the author’s conclusion doesn’t apply.

Summarize Argument

The author concludes that, when humans begin to tap into the tremendous source of creativity and innovation, that many problems that seem insurmountable today will be within our ability to solve. To support this, the author notes that over 90% of the brain remains unused (a sub-conclusion that is supported by the observation that many people with significant brain damage experience no noticeable negative effects).

Identify and Describe Flaw

The author assumes that the large portion of the brain that currently serves no purpose could be a source of creativity and innovation. From the information given, we have no reason to believe that these parts of the brain are a potential source of creativity and innovation––they could, for example, be purely structural with no potential to impact one’s creativity.

A

The argument presumes, without providing justification, that the effects of brain damage are always easily detectable.

The argument does not make this assumption––there is no indication that brain damage is ever (or always) “easily” detectable.

B

The argument presumes, without providing justification, that the only reason that any problem remains unsolved is a lack of creativity and innovation.

A lack of creativity and innovation is presumed to be a reason that some problems haven’t been solved, but the argument does not presume that a lack of creativity and innovation is the only reason for any unsolved problem.

C

The argument infers that certain parts of the brain do nothing merely on the basis of the assertion that we do not know what they do.

The argument does not make this inference merely based on the fact that we don’t know what these parts of the brain do. Instead, the inference is based on the observation that significant brain damage does not have discernible adverse effects in many people.

D

The argument infers that problems will be solved merely on the basis of the claim that they will be within our ability to solve.

The argument does not make this inference. The argument does not claim that these problems will be solved; the argument only says that the problems will be in our ability to solve.

E

The argument presumes, without providing justification, that the currently unused parts of the brain are a potential source of tremendous creativity and innovation.

The author says that 90% of the human brain is unused, then in the conclusion jumps to the claim about “this tremendous source of creativity and innovation.” We have no reason to believe that the unused parts of the brain are a potential source of creativity and innovation.