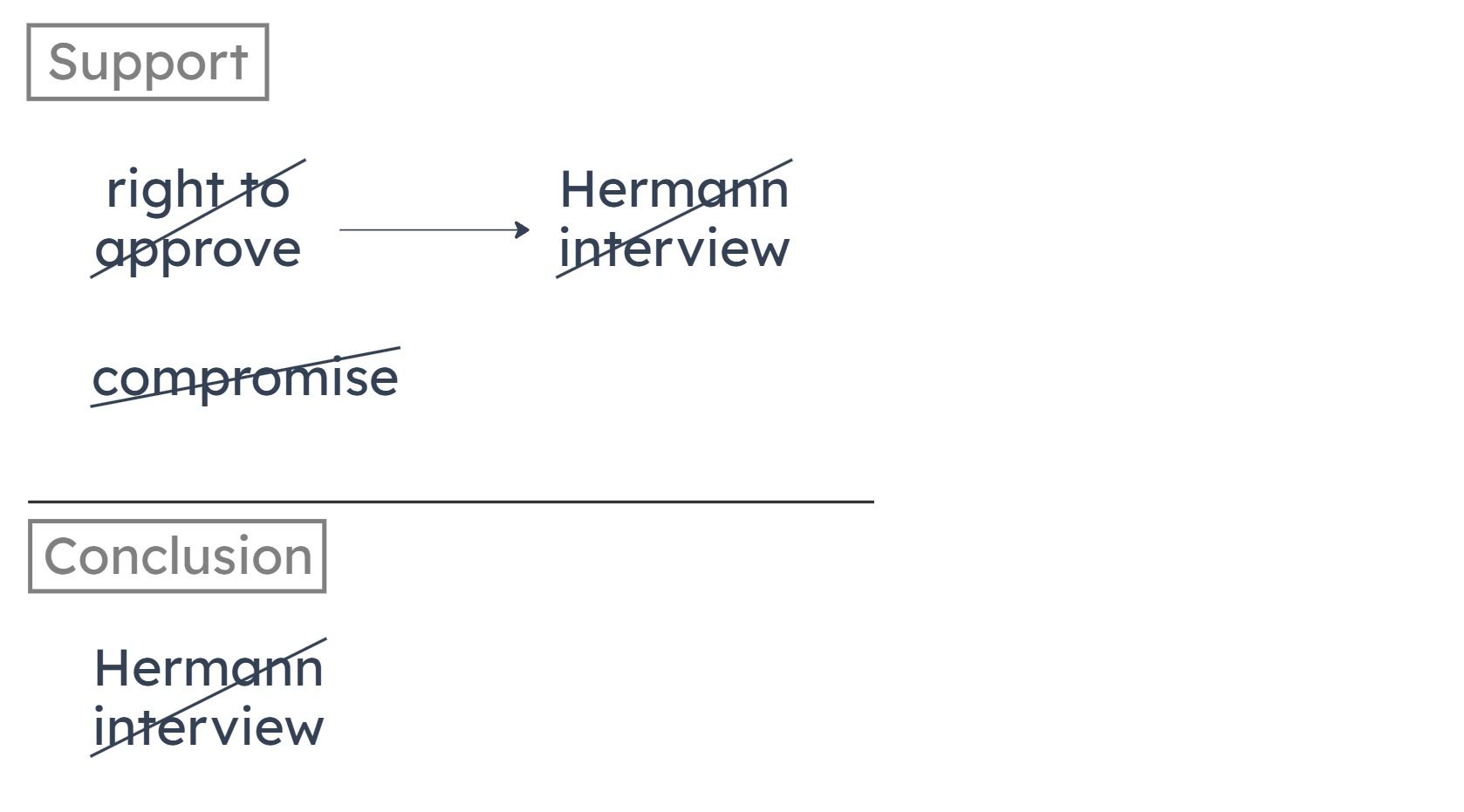

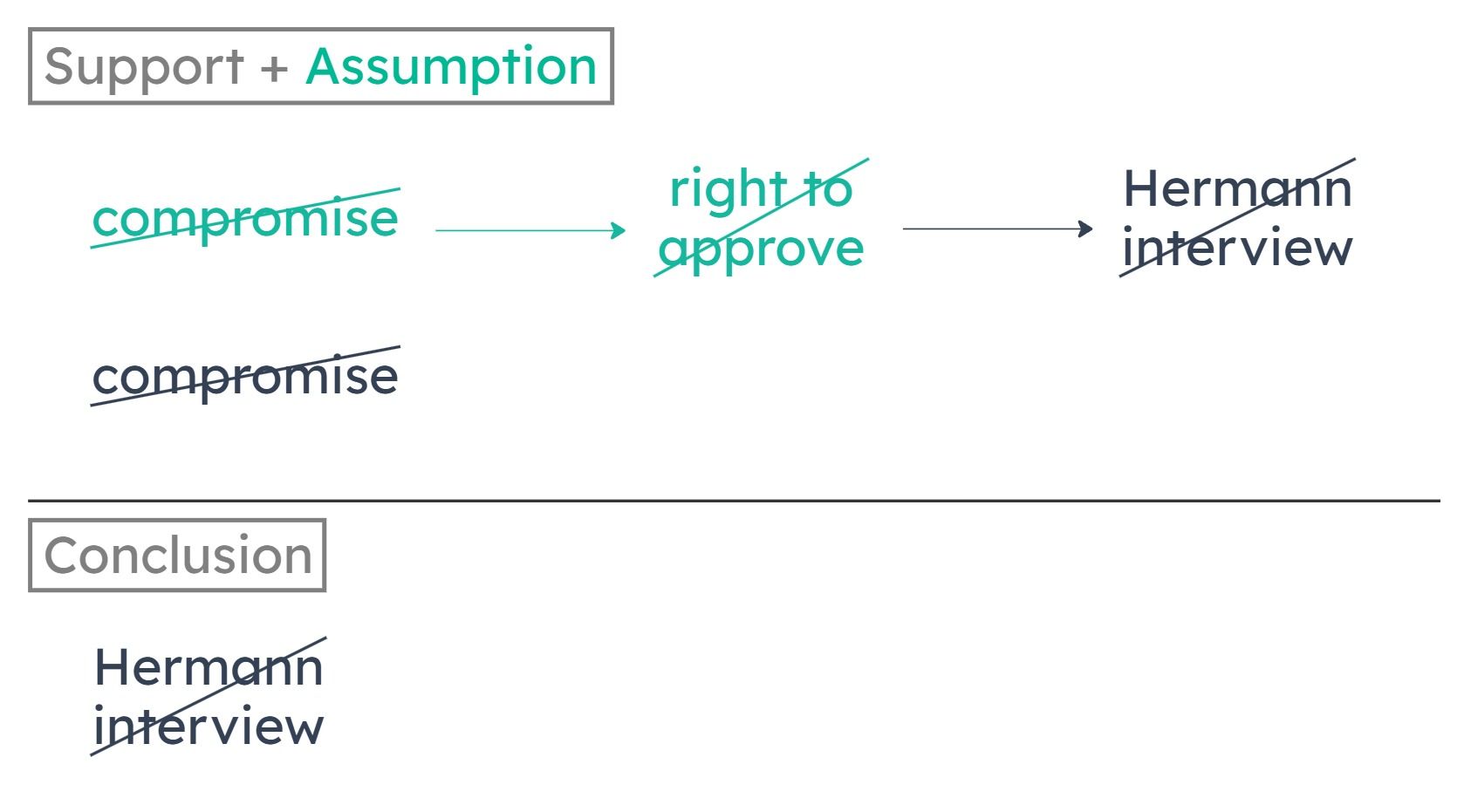

The television star Markus Hermann refuses to grant interviews with newspapers unless he is given the right to approve the article before publication. The Greyburg Messenger newspaper refuses to do anything that its editors believe will compromise their editorial integrity. So the Messenger will not interview Hermann, since _______.

Summary

The author concludes that the Messenger will not interview Hermann. This is based on the fact that the Messenger won’t do anything that its editors believe will compromise their editorial integrity. In addition, in order to interview Hermann, he must be given the right to approve the article before publication.

Missing Connection

We know that if the editors think something will compromise their editorial integrity, the Messenger won’t do it. So to conclude that the Messenger won’t interview Hermann, we want to know that the editors think interviewing Hermann will compromise their editorial integrity, or that they think that what Hermann requires in order to conduct the interview (the right to approve the article before publication) will compromise their editorial integrity.

A

the editors of the Messenger believe that giving an interviewee the right to approve an article before publication would compromise their editorial integrity

(A), in connection with one of the premises, establishes that the Messenger will not grant Hermann the right to approve the article. Then, since Hermann won’t grant an interview unless he is given the right, (A) establishes that Hermann won’t grant the interview.

B

the Messenger has never before given an interviewee the right to approve an article before publication

(B) doesn’t establish that the Messenger won’t grant Hermann the right to pre-publication approval. Just because it’s never happened before doesn’t guarantee that it won’t happen this time.

C

most television stars are willing to grant interviews with the Messenger even if they are not given the right to approve the articles before publication

We know Hermann won’t grant an interview without pre-publication approval rights. What other TV stars do doesn’t matter.

D

Hermann usually requests substantial changes to interview articles before approving them

What Hermann actually does with pre-publication approval rights doesn’t matter. The issue is whether granting him the pre-publication approval rights is something that editors think compromises their editorial integrity.

E

Hermann believes that the Messenger frequently edits interviews in ways that result in unflattering portrayals of the interviewees

What Hermann beleives about Messenger edits doesn’t matter. The issue is whether granting him the pre-publication approval rights is something that editors think compromises their editorial integrity.

A

bases its conclusion on claims that are inconsistent with each other

B

takes for granted that any presentation that is not ineffective is a good presentation

C

bases an endorsement of a product entirely on that product’s popularity

D

fails to consider that a tool might not effectively perform its intended function

E

rejects a claim because of its source rather than its content

A

The Cape Simmons Nature Preserve is one of the few areas of pristine wilderness in the region.

B

The companies drilling for oil at Alphin Bay never claimed that drilling there would not cause any environmental damage.

C

The editorialist believes that oil drilling should not be allowed in a nature preserve unless it would cause no environmental damage.

D

There have been no significant changes in oil drilling methods in the last five years.

E

Oil drilling is only one of several industrial activities that takes place at Alphin Bay.

Very clever argument. We're told that we have two groups of patients, 43 to each group. Everyone's got the same illness and receiving the same treatment. The ONLY difference is that one group is the kumbaya group. You know, we want to test the effectiveness (if it exists) of kumbaya so we isolate it. Okay, so... this is exciting what are the results? Well, the next premise tells us that after 200 years, everyone's dead. Therefore (the conclusion says), kumbaya does nothing.

See how ridiculous that argument is? I know I said 200 years whereas the actual premise said 10 years. But, 10 could also be just as ridiculous depending on what assumptions we entertain. How old are the patients? If they're 20 years old, then okay, fine, 10 years is whatever. If they're 100 years old already, then a 10 years later result is ridiculous to report. Of course everyone's dead.

That's precisely the subtly that (C) calls out. (C) says "Look, you should have reported on the results 8 years after, not 10. If you reported 8 years later, then most of the kumbaya group would be alive, while most of the non-kumbaya group would be dead."

(A) is tempting and it certainly doesn't help the argument, but it's a big stretch to say that it hurts the argument. First, we're left with just 4 data points of the original 86. It would be overgeneralizing to say something about the 86 sample from the 4 data points. Second, consider just the data points themselves. All we're told is that the kumbaya 2 lived longer than the non-kumaya 2. Okay, how much longer? 5 years? That'd be nice. Or just 5 seconds? That'd be useless.

A

Of the 4 patients who survived more than 10 years, the 2 who had attended weekly support group meetings lived longer than the 2 who had not.

B

For many diseases, attending weekly support group meetings is part of the standard medical treatment.

C

The members of the group that attended weekly support group meetings lived 2 years longer, on average, than the members of the other group.

D

Some physicians have argued that attending weekly support group meetings gives patients less faith in the standard treatment for disease T.

E

Everyone in the group whose members attended weekly support group meetings reported after 1 year that those meetings had helped them to cope with the disease.

Further Explanation

Very clever argument. We're told that we have two groups of patients, 43 to each group. Everyone's got the same illness and receiving the same treatment. The ONLY difference is that one group is the kumbaya group. You know, we want to test the effectiveness (if it exists) of kumbaya so we isolate it. Okay, so... this is exciting what are the results? Well, the next premise tells us that after 200 years, everyone's dead. Therefore (the conclusion says), kumbaya does nothing.

See how ridiculous that argument is? I know I said 200 years whereas the actual premise said 10 years. But, 10 could also be just as ridiculous depending on what assumptions we entertain. How old are the patients? If they're 20 years old, then okay, fine, 10 years is whatever. If they're 100 years old already, then a 10 years later result is ridiculous to report. Of course everyone's dead.

That's precisely the subtly that (C) calls out. (C) says "Look, you should have reported on the results 8 years after, not 10. If you reported 8 years later, then most of the kumbaya group would be alive, while most of the non-kumbaya group would be dead."

(A) is tempting and it certainly doesn't help the argument, but it's a big stretch to say that it hurts the argument. First, we're left with just 4 data points of the original 86. It would be overgeneralizing to say something about the 86 sample from the 4 data points. Second, consider just the data points themselves. All we're told is that the kumbaya 2 lived longer than the non-kumaya 2. Okay, how much longer? 5 years? That'd be nice. Or just 5 seconds? That'd be useless.

Sufficient Assumption question, pretty standard, cookie cutter question that we should be able to anticipate the answer choice.

But, it's difficult because of the embedded argument within an argument, heavy use of referential phrasing, and grammar parsing.

Author's argument begins with "however". The text before "however" is just context/other people's argument that will later serve as the referent for a referential phrase used in the conclusion.

"one must mine the full imp... to make intell prog"

Think about what's necessary and what's sufficient in this relationship. Does mining the full imp guarantee that we'll make intell prog? No. It's the other way around.

"for this, thinkers need intell discipline"

What does "this" refer to?

If you answer both of the above questions correctly, you'll end up with the proper translation of the premise below:

intell prog --> mine full imp --> intell discipline

The conclusion says "this argument for free thought fails". This takes a bit of interpreting. Look at all the text before "however". That's where we get the argument for "free thought". What's the conclusion? Focus on the indicator "because". The conclusion is "free thought is a precondition for intell prog". Now, what's the relationship here? A precondition. Something we must have. A necessary condition.

intell prog --> free thought

That's just the contextual conclusion though. Our author is arguing that that's wrong.

NOT (intell prog --> free thought)

Fully translated, it looks like this:

intell prog --> mine full imp --> intell discipline

_______________

NOT (intell prog --> free thought)

So, how do we make this argument valid? We can make intell discipline imply NO free thought. (C) gives us the contrapositive.

free thought --> NO intell discipline.

Sufficient Assumption question, pretty standard, cookie cutter question that we should be able to anticipate the answer choice.

But, it's difficult because of the embedded argument within an argument, heavy use of referential phrasing, and grammar parsing.

Author's argument begins with "however". The text before "however" is just context/other people's argument that will later serve as the referent for a referential phrase used in the conclusion.

"one must mine the full imp... to make intell prog"

Think about what's necessary and what's sufficient in this relationship. Does mining the full imp guarantee that we'll make intell prog? No. It's the other way around.

"for this, thinkers need intell discipline"

What does "this" refer to?

If you answer both of the above questions correctly, you'll end up with the proper translation of the premise below:

intell prog --> mine full imp --> intell discipline

The conclusion says "this argument for free thought fails". This takes a bit of interpreting. Look at all the text before "however". That's where we get the argument for "free thought". What's the conclusion? Focus on the indicator "because". The conclusion is "free thought is a precondition for intell prog". Now, what's the relationship here? A precondition. Something we must have. A necessary condition.

intell prog --> free thought

That's just the contextual conclusion though. Our author is arguing that that's wrong.

NOT (intell prog --> free thought)

Fully translated, it looks like this:

intell prog --> mine full imp --> intell discipline

_______________

NOT (intell prog --> free thought)

So, how do we make this argument valid? We can make intell discipline imply NO free thought. (C) gives us the contrapositive.

free thought --> NO intell discipline.