Parent Q: That would be pointless. Technology advances so rapidly that the computers used by today’s kindergartners and the computer languages taught in today’s high schools would become obsolete by the time these children are adults.

Summarize Argument

Parent Q concludes that computers should not be introduced in kindergarten and taught throughout high school. Why? Because of technology’s rapid progress, which means particular devices and languages used by students will not be used when those children are adults.

Notable Assumptions

Parent Q assumes there’s no other reason that learning on today’s computers and with today’s languages would be useful to students, besides using those same devices and languages later in life.

A

When technology is advancing rapidly, regular training is necessary to keep one’s skills at a level proficient enough to deal with the society in which one lives.

This does not counter parent Q’s objection. It introduces regular training as a condition for adults to have computer skills, but doesn’t imply people will benefit from training as students.

B

Throughout history people have adapted to change, and there is no reason to believe that today’s children are not equally capable of adapting to technology as it advances.

This doesn’t say that learning about computers throughout school would be useful to students. Students’ ability to adapt does not itself justify their studying skills that will become obsolete in the future.

C

In the process of learning to work with any computer or computer language, children increase their ability to interact with computer technology.

This refutes parent Q’s assumption that learning computer skills will only be useful if students use the exact same technologies as adults. It implies those skills will be transferrable to later computer technologies.

D

Automotive technology is continually advancing too, but that does not result in one’s having to relearn to drive cars as the new advances are incorporated into new automobiles.

This analogy presents a weak counter to parent Q’s claim. It’s possible the way people interact with computers will change more significantly than the way people interact with vehicles.

E

Once people have graduated from high school, they have less time to learn about computers and technology than they had during their schooling years.

This gives a reason to support parent P’s conclusion, but does not address the objection raised by parent Q. If students are learning irrelevant skills, their training will be pointless regardless of how much time they have to learn them.

Summary

The author concludes that the information in typical broadcast news stories is poorly organized. This is based on the following:

Most people feel that they’re confused by info in broadcast news. This could be due to the info being delivered too quickly or to its being poorly organized. But, the author attempts to eliminate the “too quickly” explanation by pointing out that the content of a typical news story shows that most people can handle far more density of info than the average info density of a news story.

Most people feel that they’re confused by info in broadcast news. This could be due to the info being delivered too quickly or to its being poorly organized. But, the author attempts to eliminate the “too quickly” explanation by pointing out that the content of a typical news story shows that most people can handle far more density of info than the average info density of a news story.

Notable Assumptions

The author assumes that the fact people can handle a higher density of info than what’s found in a typical news story indicates that people are not confused by the news info being delivered too quickly.

The author also overlooks the possibility that there are other explanations besides being delivered too quickly or being poorly organized that might account for why people are confused by info from broadcast news.

The author also overlooks the possibility that there are other explanations besides being delivered too quickly or being poorly organized that might account for why people are confused by info from broadcast news.

A

It is not the number of broadcast news stories to which a person is exposed that is the source of the feeling of confusion.

Necessary, because if this isn’t true — if the number of news stories that a person is exposed to is the source of confusion — then that undermines the author’s theory that the reason for confusion must be the poor organization of stories. Notice that the author’s premise concerning information density only related to the density of info in a typical story; this overlooks the potential impact of being exposed to many stories.

B

Poor organization of information in a news story makes it impossible to understand the information.

Not necessary, because the argument concerns the cause of confusion. One can still be confused by the info in a story, even if it’s possible to understand the info.

C

Being exposed to more broadcast news stories within a given day would help a person to better understand the news.

Not necessary, because the author believes poor organization is the cause of confusion. So although the author thinks better organization would help someone be less confused, that doesn’t imply the author must think that having more news stories would help someone be less confused.

D

Most people can cope with a very high information density.

We know that most people can cope with more density than that found in a typical news story. This doesn’t imply the author thinks most people can cope with a “very high” info density. Maybe the info density of a news story is low, and people can cope with just slightly more.

E

Some people are being overwhelmed by too much information.

Summarize Argument

Our argument concludes that there are no guidelines for defining objects as art. It supports that conclusion by identifying an attribute called representation, which is present in some art and dependent upon the art’s context. The argument then says there are no guidelines for determining aspects of art that rely on context (including representation), which the argument then stretches into the conclusion that there are no guidelines for defining art.

Identify and Describe Flaw

What if determining whether or not an object has representation is not the only way to identify it as art? Our author never defined representation as a necessary aspect for art; in fact, they told us that only some art has it. They failed to exclude the possibility that other attributes are sufficient for calling something art.

A

because some works of art are nonrepresentational, there is no way of judging our aesthetic experience of them

Our conclusion depends on characteristics and relationships associated with representational art; because this AC deals with nonrepresentational art, it goes outside the scope of our argument and does not correctly identify a flaw.

B

an object may have some aesthetic properties and not be a work of art

Irrelevant. Similarly to A, this AC goes outside the scope of our argument—we’re dealing with one specific aesthetic property and things that are art, not with other properties or non-art things.

C

aesthetically relevant properties other than representation can determine whether an object is a work of art

This addresses our argument’s underlying assumption. If aesthetically relevant properties other than representation can qualify something as art, our author’s argument is moot.

D

some works of art may have properties that are not relevant to our aesthetic experience of them

This is consistent with the argument and does not impact the validity of its conclusion. Properties like weight or smell probably don’t impact an artwork's aesthetic. The truth of this statement has nothing to do with our conclusion and does not make its logic flawed.

E

some objects that represent things other than themselves are not works of art

Similarly to A and B, this AC reaches outside the scope of our argument. The stimulus focuses on things that are art and have context-dependent properties. If something is not art, that does not impact the strength of the conclusion.

Summary

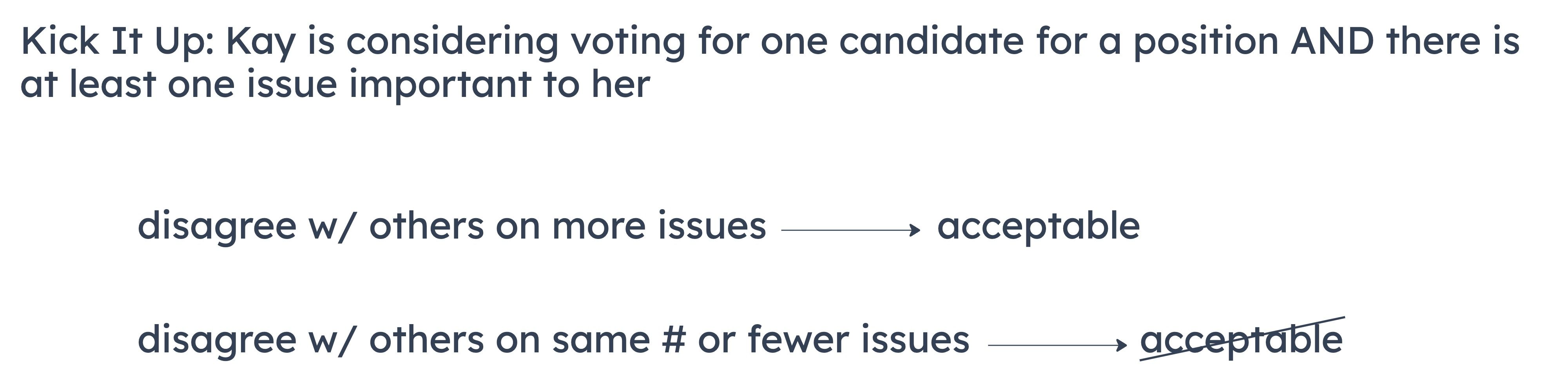

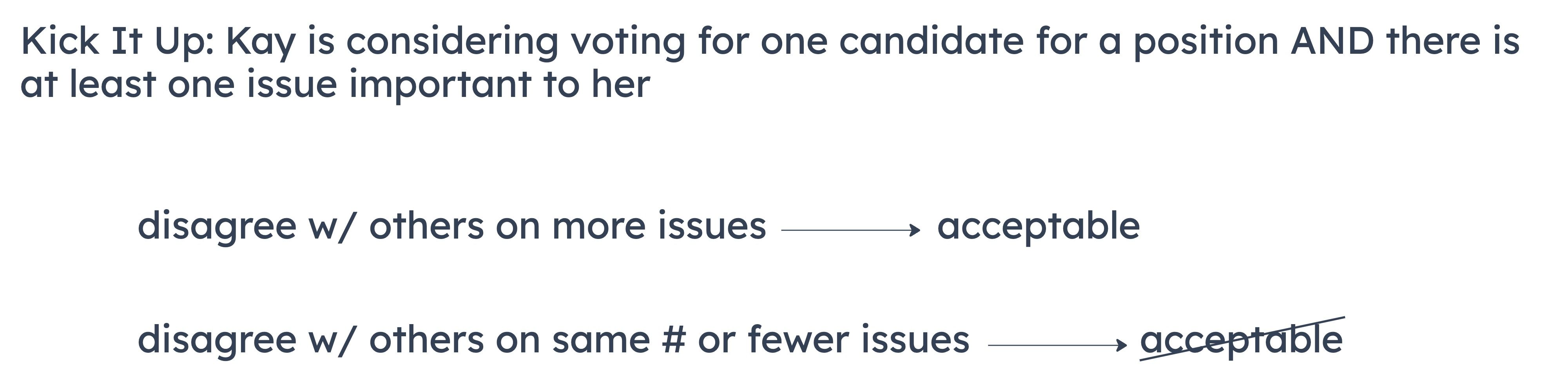

When there’s at least one issue important to Kay, then it’s acceptable for her to vote for a person with whom she disagrees on an important issue IF she disagrees with every other candidate on a greater number of important issues. If she does not disagree with every other candidate on a greater number of important issues, she cannot vote for a person with whom she disagrees about an important issue. In the upcoming election, the three candidates are L, M, and N. There’s only 1 issue important to Kay. Kay agrees with M on that issue, but she disagrees with N and L on that issue.

Notable Valid Inferences

The question stem asks us to draw an inference about "any" election. So we should pick an answer that logically follows from one of the principles. The details about the upcoming mayoral election aren't relevant to this question stem.

A

If there are no issues important to her, it is unacceptable for her to vote for any candidate in the election.

Could be false. We don’t know what is acceptable or unacceptable when there are no issues important to Kay.

B

If she agrees with each of the candidates on most of the issues important to her, it is unacceptable for her to vote for any candidate in the election.

Could be false. It’s acceptable for her to vote for one of the candidates if she disagrees with all the other candidates on a greater number of important issues. Maybe she agrees with one cand. on 80% of imp. issues, but with the other candidates only on 70%.

C

If she agrees with a particular candidate on only one issue important to her, it is unacceptable for her to vote for that candidate.

Could be false. It’s acceptable for her to vote for that candidate if she disagrees with each of the other candidates on a greater number of important issues. She might disagree with the other candidates on every issue, for example.

D

If she disagrees with each of the candidates on exactly three issues important to her, it is unacceptable for her to vote for any candidate in the election.

Must be true. If she doesn’t disagree with each of the other candidates on a greater number of important issues, it’s unacceptable for her to vote for a candidate with whom she disagrees on an important issue. Here, she disagrees with each candidate on the same # of imp. issues.

E

If there are more issues important to her on which she disagrees with a particular candidate than there are such issues on which she agrees with that candidate, it is unacceptable for her to vote for that candidate.

Could be false. It’s acceptable for her to vote for that candidate if she disagrees with each other candidate on a greater number of important issues. She might disagree with one candidate on 55% of imp. issues, but disagree with everyone else on 70%, for example.