Mathematics professor: I disagree. My applied statistics course covers much of the same material taught in the applied statistics courses in social science departments. In fact, my course uses exactly the same textbook as those courses!

Summarize Argument: Counter-Position

The math professor concludes that non-social science departments should teach applied statistics. This in contrast to the psychologist, who thinks that social science departments are best at teaching their students how to apply statistics to their disciplines. The math professor disagrees, because his applied statistics course covers the exact same content as those taught by the social science departments.

Identify and Describe Flaw

Even if the math professor’s statistics course covers the same material, it may not teach students to apply it to a social science as effectively as a course taught by an expert in the field. That was the point made by the psychology professor, and the math professor didn’t address it.

A

The response gives no evidence for its presumption that students willing to take a course in one department would choose a similar course in another.

Student preference is never mentioned in the response, so this can’t be the flaw.

B

The response gives no evidence for its presumption that social science students should have the same competence in statistics as mathematics students.

The math professor never says anything about student competence, so this can’t be the flaw.

C

The response does not effectively address a key reason given in support of the psychology professor’s position.

The psychology professor’s main claim—that a social science expert is best suited to teach students how to apply statistics in that field—is never addressed.

D

The response depends for its plausibility on a personal attack made against the psychology professor.

No personal attack is made, so this can’t be the flaw.

E

The response takes for granted that unless the course textbook is the same the course content will not be the same.

This is saying: If the content is the same, then the textbook is the same. The math professor doesn’t take this for granted. At most, he’s saying that, if the textbook is the same, the course is the same.

Summary

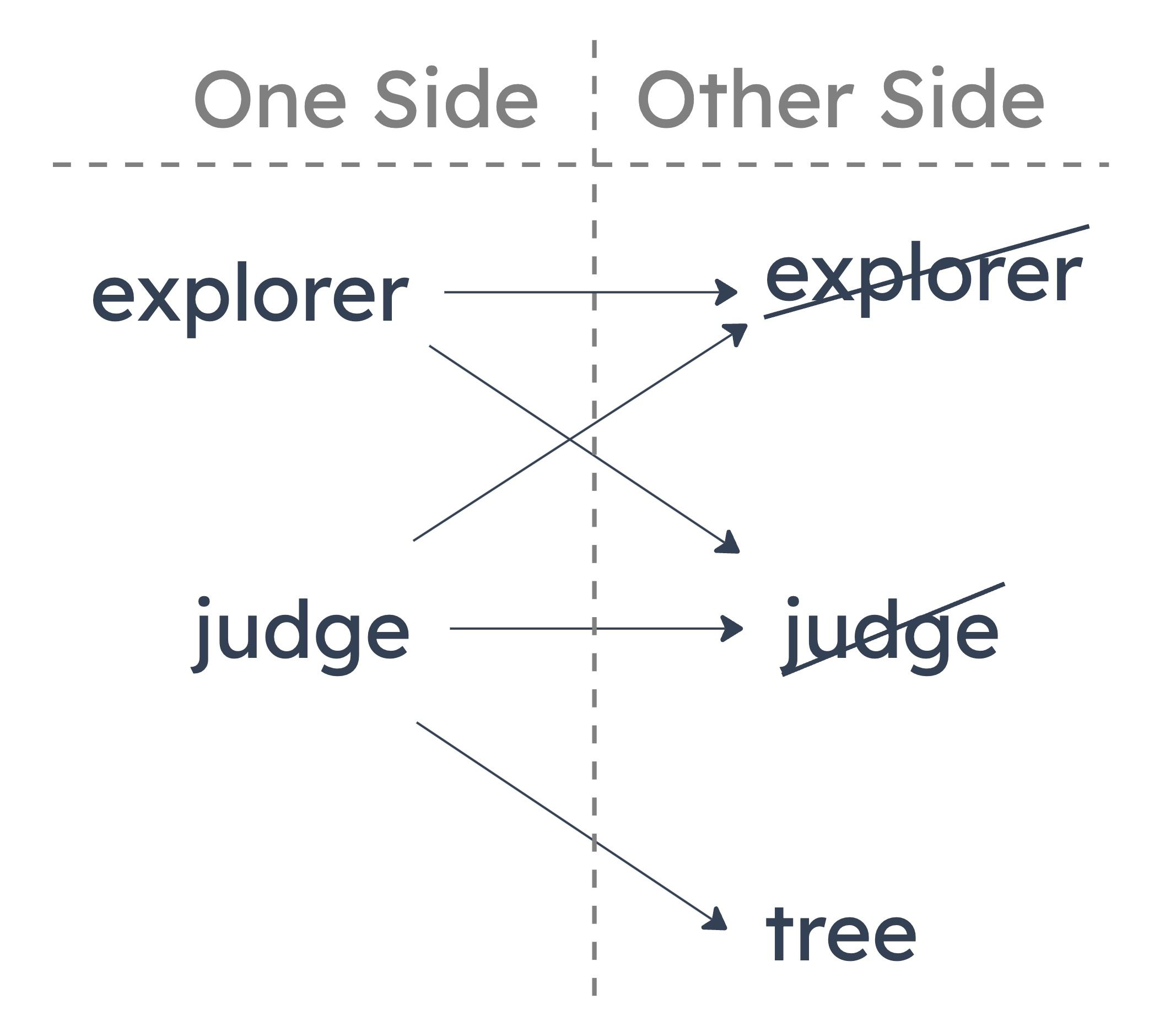

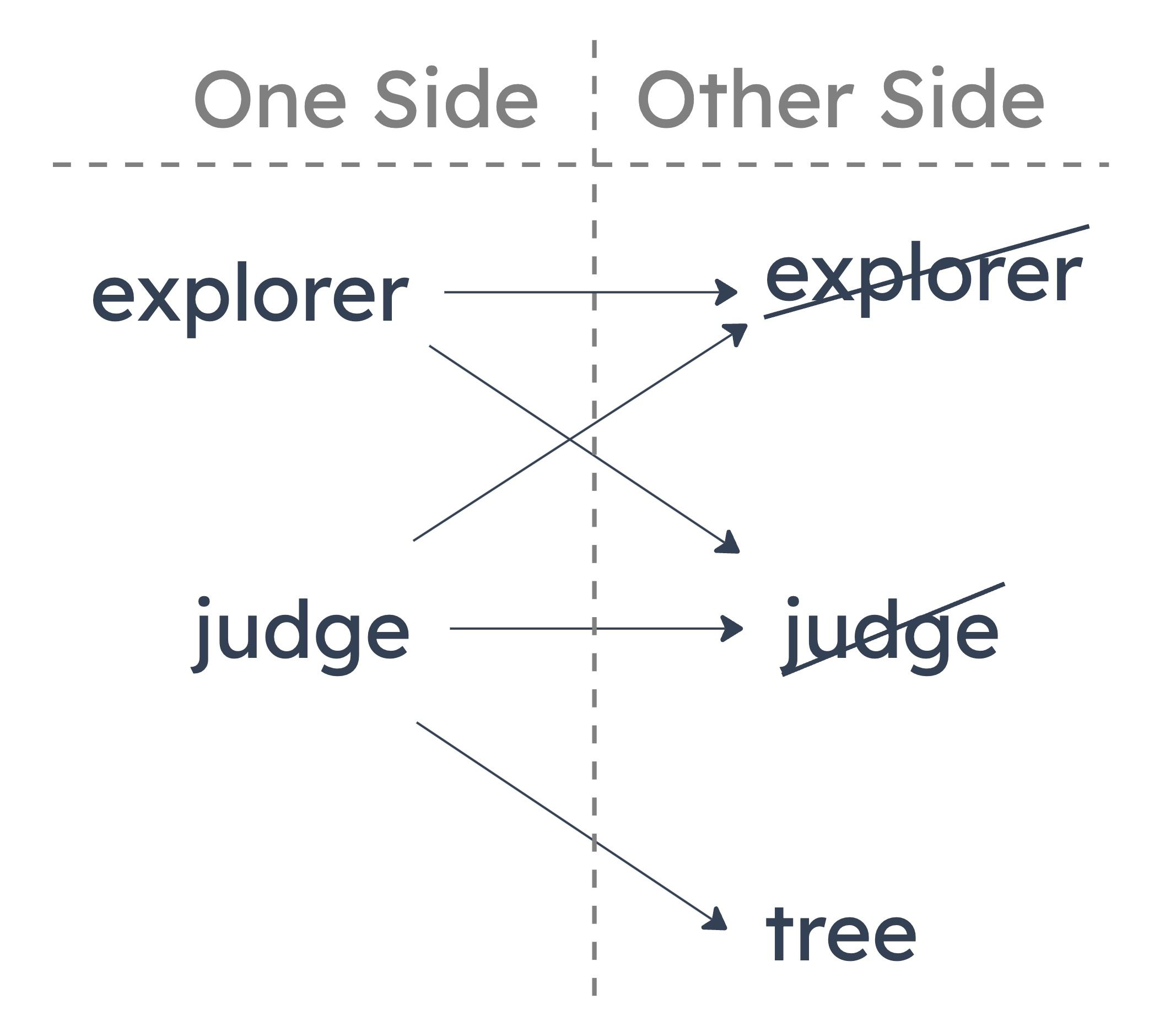

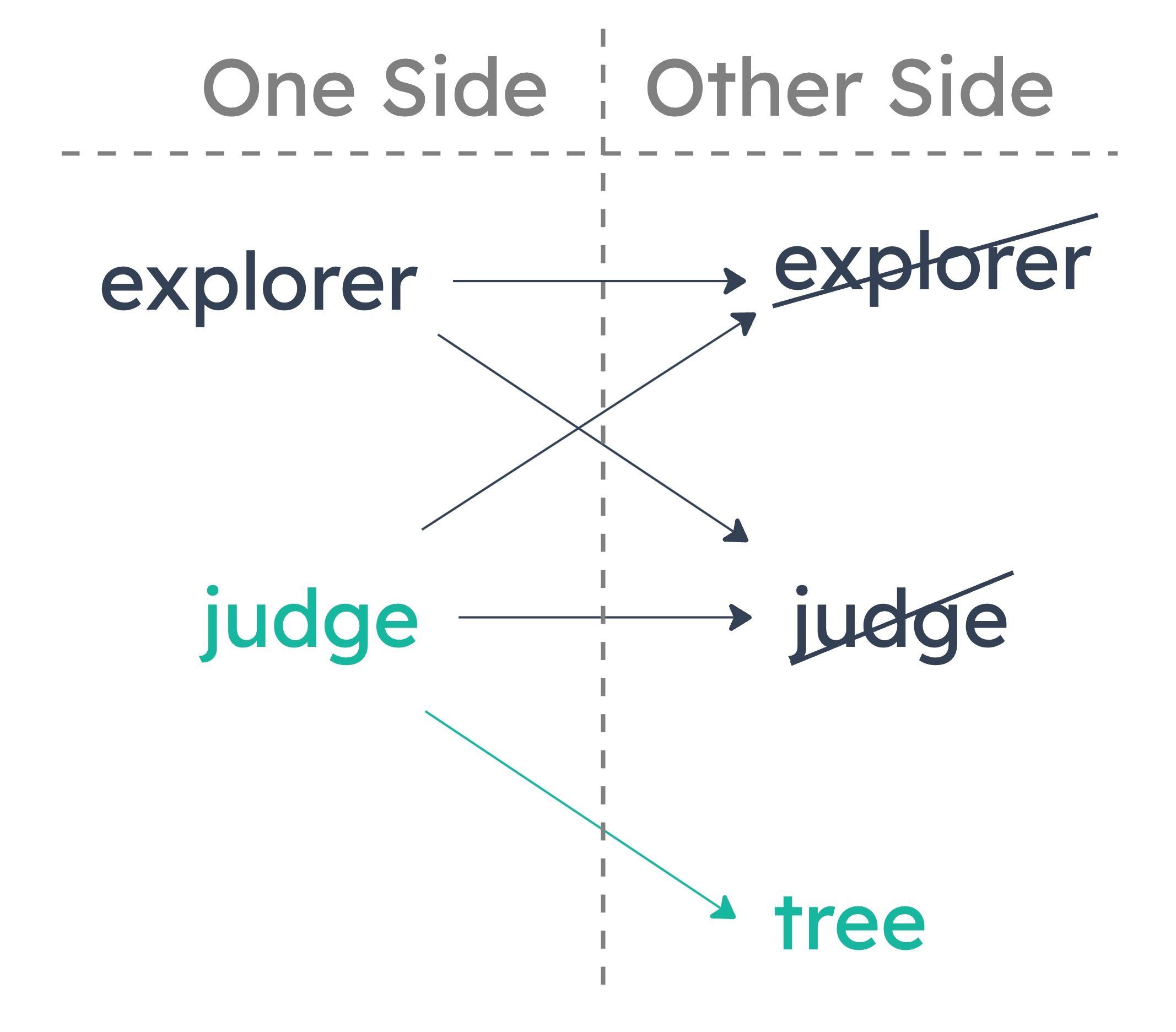

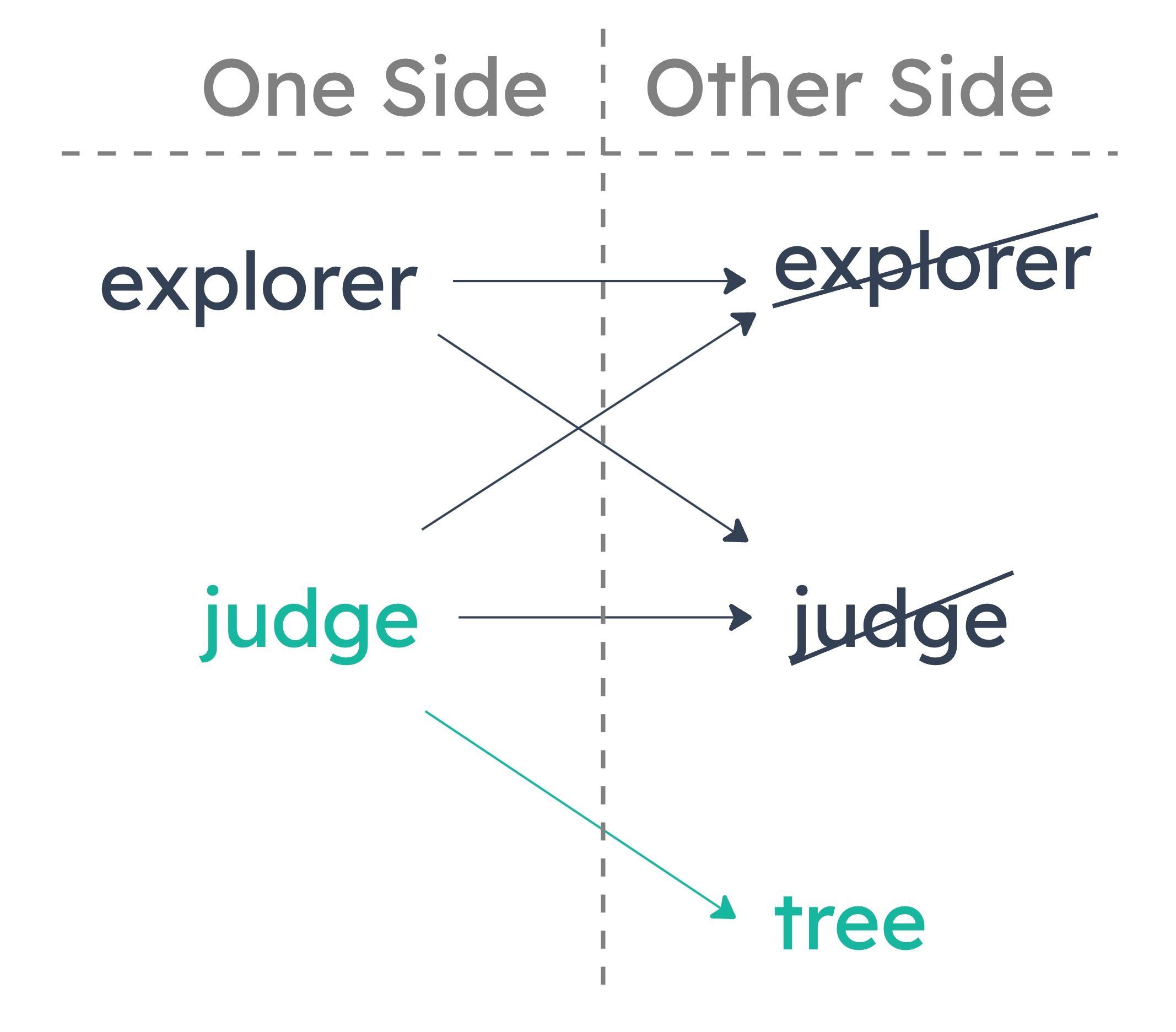

The stimulus can be diagrammed as follows:

Notable Valid Inferences

If you have a judge’s head on one side, you must have a tree on the other side.

If you have an explorer’s head on one side, you can have a building or a tree on the other side.

If you have a building on one side, you can have a building, a tree, or an explorer’s head on the other side.

If you have a tree on one side, you can have a tree, a judge’s head, an explorer’s head, or a building on the other side.

If you have an explorer’s head on one side, you can have a building or a tree on the other side.

If you have a building on one side, you can have a building, a tree, or an explorer’s head on the other side.

If you have a tree on one side, you can have a tree, a judge’s head, an explorer’s head, or a building on the other side.

A

All those with an explorer’s head on one side have a building on the other.

This could be false. A coin with an explorer’s head on one side could have a building OR a tree on the other side.

B

All those with a tree on one side have a judge’s head on the other.

This could be false. Any coin with a tree on one side could have a tree, a building, an explorer’s head, or a judge’s head on the other side. (We know JH→T, but it would be confusing the sufficient and necessary conditions to claim that T→ JH).

C

None of those with a tree on one side have an explorer’s head on the other.

This could be false. A coin with a tree on one side can have a tree, a building, an explorer’s head, or a judge’s head on the other side.

D

None of those with a building on one side have a judge’s head on the other.

This must be true. Any coin with a judge’s head on one side must have a tree on the other side, so a coin with a judge’s head on one side would not have a building or an explorer’s head on the other side.

E

None of those with an explorer’s head on one side have a building on the other.

This could be false. A coin with an explorer’s head on one side could have a building or a tree on the other side.

Summarize Argument

The author concludes that there are no endangered species of ants. Why? Because insects in general are so successful that they spread into virtually every ecosystem, and ants are the most successful insect.

Identify and Describe Flaw

This is the cookie-cutter flaw of confusing part v. whole. The author observes that the biological family of ants is successful, and concludes that every individual ant species must be successful.

But some qualities can be true of a whole without being true of every part, or vice versa. Ants in general could be very successful, but some species of ants could still be endangered.

But some qualities can be true of a whole without being true of every part, or vice versa. Ants in general could be very successful, but some species of ants could still be endangered.

A

the Arctic Circle and Tierra del Fuego do not constitute geographically isolated areas

The author doesn’t presume that either is isolated; they’re used to demonstrate wide geographic range (extreme north vs. extreme south).

B

because ants do not inhabit only a small niche in a geographically isolated area, they are unlike most other insects

The author says that insects are definitely not the kind of animals limited to small niches, so this can’t be the flaw.

C

the only way a class of animal can avoid being threatened is to spread into virtually every ecosystem

This goes beyond what the argument states. The author says that two options for animal species are to go extinct or spread into virtually every ecosystem. He doesn’t indicate that those are the only two options.

D

what is true of the constituent elements of a whole is also true of the whole

This describes the part-to-whole flaw, but this is the reverse of what the author does. Instead, he commits a whole-to-part flaw; he attributes a property true of a whole (ants as a family) to each of its individual parts (individual species of ants).

E

what is true of a whole is also true of its constituent elements

This is the cookie-cutter whole-to-part flaw. The author takes for granted that a property true of a whole (ants as a whole are successful) is also true of the parts making up that whole (every individual ant species is successful). But that's flawed reasoning. Even if ants are generally successful, individual ant species could be endangered.

Summarize Argument: Phenomenon-Hypothesis

The analyst hypothesizes that university administrators tend not to choose university professors who do not pursue research for scientific administration positions. This is based on a phenomenon demonstrated by a recent survey: biology professors who don’t pursue research are underrepresented in scientific administrative positions.

Notable Assumptions

The analyst assumes a causal relationship based on a correlation. Specifically, the analyst assumes that the underrepresentation of professors who do not pursue research in scientific administrative positions is caused by their choice not to engage in research.

A

In universities there are fewer scientific administrative positions than there are nonscientific administrative positions.

This does not affect the argument. Nonscientific administrative positions are not relevant to, and outside the scope of, the argument.

B

Biologists who do research fill a disproportionately low number of scientific administrative positions in universities.

This weakens the argument. It attacks the assumption that the professors’ failure to pursue research leads to their underrepresentation in science admin positions (instead of another factor), which implies that those who pursue research would be better represented in these roles.

C

Biology professors get more than one twentieth of all the science grant money available.

This does not affect the argument. Grant money is not relevant to, and outside the scope of, the argument.

D

Conducting biological research tends to take significantly more time than does teaching biology.

This does not affect the argument. The time it takes to conduct research is not relevant to, and outside the scope of, the argument.

E

Biologists who hold scientific administrative positions in the university tend to hold those positions for a shorter time than do other science professors.

This does not affect the argument. The argument is concerned with one’s likeliness to be appointed to a scientific administration position in the first place. The time biologists spend in these positions is outside the scope of the argument.

Summarize Argument

Catmull concludes that historians never determine what actually happened in the past. Why? Because different historians always arrive at different conclusions when studying the same events.

Identify and Describe Flaw

Catmull claims that, because historians disagree, they never arrive at the truth. The flaw in his reasoning is that some historians may still have arrived at the truth, even if not all of them have. The fact that they disagree shows that not all of them can be right, but it doesn’t show that all of them are wrong.

A

draws a conclusion that simply restates a claim presented in support of that conclusion

This is the cookie-cutter flaw of circular reasoning; it doesn’t apply here. Catmull’s conclusion is an unwarranted leap from his premise, not a restatement of it.

B

concludes, solely on the basis of the claim that different people have reached different conclusions about a topic, that none of these conclusions is true

Catmull assumes that, because historians disagree about the past, none of their conclusions can be true. He overlooks the possibility that some historians may have accurately determined what happened, even without universal agreement.

C

presumes, without providing justification, that unless historians’ conclusions are objectively true, they have no value whatsoever

Catmull likens historians’ conclusions to fiction, but he doesn’t suggest that this means they have no value whatsoever.

D

bases its conclusion on premises that contradict each other

Catmull’s premises don’t contradict either, so this isn’t the flaw.

E

mistakes a necessary condition for the objective truth of historians’ conclusions for a sufficient condition for the objective truth of those conclusions

This is the cookie-cutter flaw of confusing sufficiency and necessity; it isn’t applicable here because Catmull isn’t using conditional logic.