But some qualities can be true of a whole without being true of every part, or vice versa. Ants in general could be very successful, but some species of ants could still be endangered.

A

the Arctic Circle and Tierra del Fuego do not constitute geographically isolated areas

B

because ants do not inhabit only a small niche in a geographically isolated area, they are unlike most other insects

C

the only way a class of animal can avoid being threatened is to spread into virtually every ecosystem

D

what is true of the constituent elements of a whole is also true of the whole

E

what is true of a whole is also true of its constituent elements

A

In universities there are fewer scientific administrative positions than there are nonscientific administrative positions.

B

Biologists who do research fill a disproportionately low number of scientific administrative positions in universities.

C

Biology professors get more than one twentieth of all the science grant money available.

D

Conducting biological research tends to take significantly more time than does teaching biology.

E

Biologists who hold scientific administrative positions in the university tend to hold those positions for a shorter time than do other science professors.

A

draws a conclusion that simply restates a claim presented in support of that conclusion

B

concludes, solely on the basis of the claim that different people have reached different conclusions about a topic, that none of these conclusions is true

C

presumes, without providing justification, that unless historians’ conclusions are objectively true, they have no value whatsoever

D

bases its conclusion on premises that contradict each other

E

mistakes a necessary condition for the objective truth of historians’ conclusions for a sufficient condition for the objective truth of those conclusions

A

The positions taken by Muratori and Kenner on many election issues were not very similar to each other.

B

Kenner had held elected office for many years before the recent election.

C

In the year leading up to the election, Kenner was implicated in a series of political scandals.

D

Six months before the recent election, the voting age was lowered by three years.

E

In the poll, supporters of Muratori were more likely than others to describe the election as important.

Historically, in order to be viable in the long run, a party needs at least 30% of eligible voters prepared to support it by joining it or by donating money to it.

According to a recent poll, only 26% of eligible voters are prepared to join an education party, and only 16% of eligible voters are prepared to donate money to one.

A

some of those who said they were willing to donate money to an education party might not actually do so if such a party were formed

B

an education party could possibly be viable with a smaller base than is customarily needed

C

the 16 percent of eligible voters prepared to donate money to an education party might donate almost as much money as a party would ordinarily expect to get if 30 percent of eligible voters contributed

D

a party needs the appropriate support of at least 30 percent of eligible voters in order to be viable and more than half of all eligible voters support the idea of an education party

E

some of the eligible voters who would donate money to an education party might not be prepared to join such a party

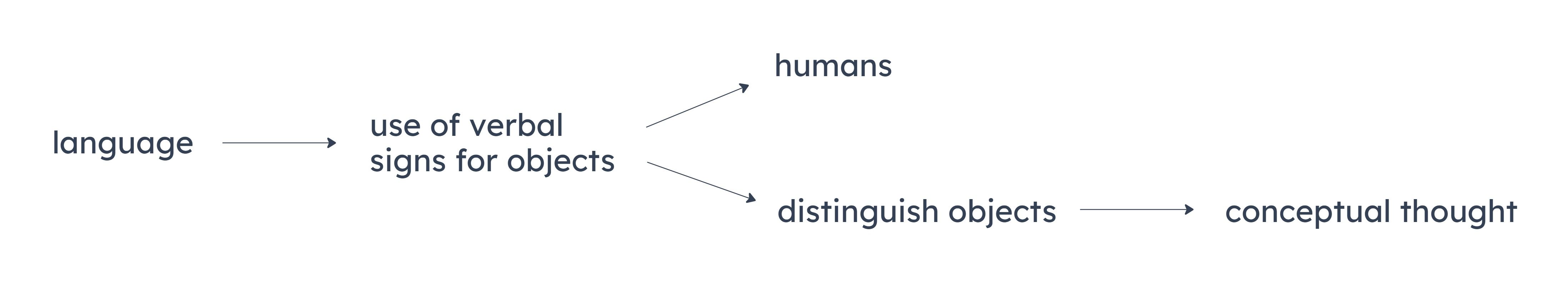

Reza: Language requires the use of verbal signs for objects as well as for feelings. Many animals can vocally express hunger, but only humans can ask for an egg or an apple by naming it. And using verbal signs for objects requires the ability to distinguish these objects from other objects, which in turn requires conceptual thought.

Summary

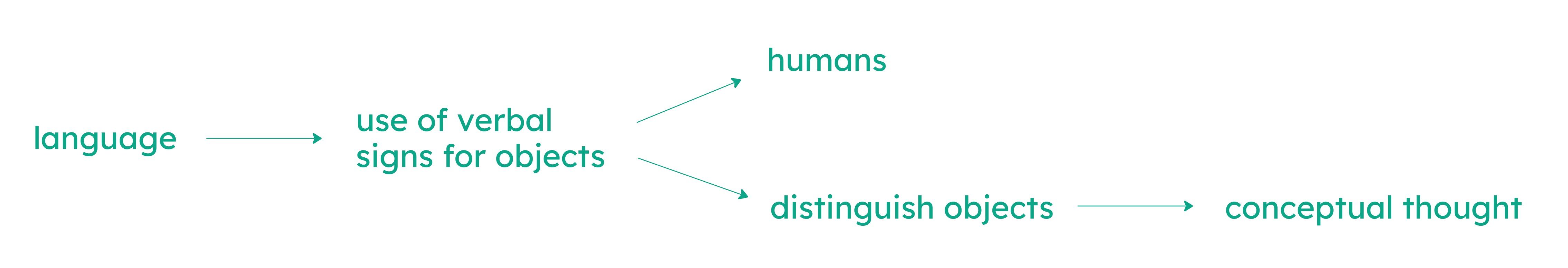

The stimulus can be diagrammed as follows:

Notable Valid Inferences

Conceptual thought is a necessary condition for language use.

Animals do not have language.

A

Conceptual thought is required for language.

This must be true. As shown in the diagram, by chaining the conditional claims, we see that conceptual thought is a necessary condition for language.

B

Conceptual thought requires the use of verbal signs for objects.

This could be false. (B) says “Conceptual thought → Use of verbal signs for objects.” In our diagram, we only have conceptual thought as a necessary condition; we don’t know what conceptual thought is a sufficient condition for.

C

It is not possible to think conceptually about feelings.

This could be false. We have no information about which topics are possible to think about conceptually.

D

All humans are capable of conceptual thought.

This could be false. In our diagram, “human” is a necessary condition for “use of verbal signs for objects.” We are not given “humans” as a sufficient condition for anything, so we don’t know anything that “all humans” can do.

E

The vocal expressions of animals other than humans do not require conceptual thought.

This could be false. We know that many animals can vocally express at least one feeling (hunger). It could be the case that vocal expression of hunger requires conceptual thought; our stimulus just doesn’t address this.